Photo: imghub.ru

“France’s capacity to sustain a high-end, conventional conflict is limited,” RAND said. “The French military might be able to accomplish all its assigned missions at once, but it lacks depth, meaning that such demanding operations would quickly exhaust both its human and material resources.”

France fields a powerful military with sophisticated capabilities, including advanced jets, well-trained commandos and nuclear weapons.

But the French military is also fragile, lacking reserves of munitions and manpower for a sustained conflict with Russia, according to a study by RAND, a U.S. think tank, FORBS quotes.

Facing possible conflict with Moscow over Eastern Europe and the Baltic States – and with the U.S. calling for Europe to spend more on its own defense – NATO needs all the help it can get.

France is well-positioned to help. With around 300,000 active-duty military personnel backed by the world’s seventh-largest economy, France boasts an impressive range of capabilities for a medium-sized power. Its Leclerc tanks, Rafale jet fighters and CAESAR 155-millimeter self-propelled howitzers are in the same league as advanced American or Russian equipment. France has a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier and four nuclear-powered submarines armed with nuclear-tipped ICBMs, as well as spy satellites and cyberwarfare capabilities.

France’s problem isn’t breadth of capabilities, but depth. Not just limited numbers of weapons and munitions, but also crucial support services, such as electronic warfare, air defense and airlift capacity.

Ironically, while France and America have had their squabbles, both find themselves caught in the same dilemma. Like the U.S. military, the French armed forces entered the post-9/11 era configured for Cold War mechanized combat. And like the U.S. military, they had to reorient themselves for counterinsurgency warfare. For years, France has been fighting Islamic militants in the former French colonies in the Sahel — or Saharan — region of Africa, including the nations of Mali, Mauritania, Chad, Niger and Burkina Faso. Since Operation Barkhane began in 2014, up to 5,000 French soldiers have been deployed in Africa, as well as small numbers of troops fighting Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

Lost in the Desert…

Lost in the Desert…

Photo: snafu-solomon.com

The result is that the French military is designed for segment median, or “middle-segment” warfare, defined as “heavy enough to survive on a conventional battlefield yet light enough to remain expeditionary — i.e., deployable to austere environments, such as Mali, in the absence of ample logistical capabilities,” RAND noted.

“France has been careful to maintain the ability to do full spectrum operations, including for a conventional war in Europe,” Stephanie Pezard, a RAND researcher who co-authored the study, told me. “However, this ability has not been their main focus over the past few years, resulting recently in a new turn toward high-intensity conflict and the means necessary to wage this type of war.”

Yet France does see itself as defending Europe – just not in Europe. “The French consider their military’s active overseas operations, especially in the Sahel but also in Iraq and Syria, as burden-sharing — a form of in-kind contribution that enhances NATO and European security even when not conducted under a NATO or European Union mandate,” RAND noted.

But France couldn’t battle Russia for long without U.S. support. “France is able to conduct military operations across the full spectrum of conflict, but it does not have the ability to sustain the fight during a protracted conflict against a highly capable adversary, such as Russia,” said RAND. “From a U.S. perspective, this means that France could participate in a large-scale conventional war in Eastern Europe for a limited time.”

Which leads to an even deeper question: how willing would France be to fight Russia? That depends, says Pezard.

Is the current French model of warfare viable? In 2021, a study with Stephanie Pezard suggested that the answer was ‘NO’. The French military — now indisputably the most capable in Western Europe — could do a lot of things very well. But it also lacked the depth and the mass to do anything on a large scale for any length of time before it simply ran out of stuff.

The war in Ukraine has only placed this problem in greater relief. Conventional combat, even in this era of precision warfare and advanced information networks, still requires enormous reserves of manpower, equipment, and ammunition. Perhaps Ukraine and Russia were not expending these things on a rate comparable to World War I, but they have seriously challenged the idea that highly professional but small “bonsai tree” militaries could get away with substituting quality for quantity, an idea that encouraged the reduction of vehicle fleets and military stores by militaries in search of post-Cold War peace dividends.

France cannot simply eschew expensive new technology and return to the mass armies of the past. French President Emmanuel Macron has evoked the idea of a “war economy,” yet the consensus in France is that this is impossible for financial and political reasons. Part of the problem is that, while it is true that, for example, French production of its howitzers and various guided missile systems is currently woefully inadequate, producing these things on a much larger scale is no easy task. The company that makes the CAESAR currently produces four a month and is expected to reach a rate of six a month by December, and then eight a month by the middle of 2024. Progress, for sure, but slow progress. France also is not about to restart tank production. Yes, a new tank is in the works — a joint Franco-German product intended to replace both the Leclerc and the Leopard 2 — but it is not scheduled to be produced until 2035, and presumably there is a limit to how much that process can be hurried. One may also safely assume that the new tank will be significantly more expensive than either the Leclerc or the Leopard 2. Finally, no one seriously discusses a return to mass military conscription, which is what made the mass armies of the past century possible.

The French approach to high-intensity warfare since the calamity of 1940 has been to privilege maneuver, speed, and “audacity” at the expense of mass and firepower.

The newer maneuver-centric approach found reinforcement in the French army’s colonial experience and its expeditionary doctrines, which likewise promoted audacity and improvisation in the absence of numbers and resources. That colonial culture has had a profound influence on the French military up to the present day because of a variety of institutional factors and the reality that, as one Foreign Legion officer has frequently told me, an “army is what it does.” The French army most of the time in recent decades has been busy with small wars in Africa. Of course, what is useful in Mali is much less useful in, say, Donetsk...

Instead, France invested significant resources into acquiring the ultimate insurance against invasion — nuclear weapons, along with the means to deliver them. The structure of the French air force and navy since has reflected that priority rather than the ability to defeat the Soviet air force and navy. They are designed to deliver nuclear warheads and protect the means to do so. All other missions are secondary. The result has been nuclear-propelled ballistic missile submarines and top-shelf combat aircraft designed with nuclear missions at the top of the requirements list. But all of this comes at the expense of mass. Besides the fact that the money required to maintain nuclear capabilities is money that is not available for other purposes, France sets aside a portion of its aircraft and ships just in case they are needed for nuclear missions, reducing the number available for other missions.

On Feb. 13, the chief of staff of the French army, Gen. Pierre Schill, presented to a group of journalists his new vision for the French army’s path forward. Interestingly, Schill’s response to the quality versus mass dilemma is to stay the course, largely by investing in the army’s ability to do better what it was already designed to do, in other words work to enhance its quality.

Schill made clear that the army would maintain its current size, which consists of 77,000 deployable troops (out of a total size of roughly 120,000). He explained that there was little value in simply buying more tanks, howitzers, etc. Rather, his vision was to focus on resilience and cohesion, to enable the army to do a better job of high-intensity warfare at its current size, and ideally to have greater stocks so that it could endure longer. It also meant backing away from the expeditionary mindset and some of the qualities that had been among its virtues.

Schill compared the French army to Lego bricks. He noted that it has operated by pulling together bricks and assembling them, often on the fly, into deployable force packages. Its virtues were modularity, but this also meant assembling forces by cobbling together bits and pieces of multiple units to provide them with specific capabilities, as required.

Philippe Chapleau similarly remarked that even with the big budget increases, the French military was doing little more than rebuilding but fundamentally would remain what it was. A fairer assessment might be that France assumes that a true mass military is beyond its reach political and fiscally, so the best it can to is to attempt to optimize the force it has, which is designed for maneuver rather than raw power.

Would this be good enough? Part of the answer, at least for the French leadership, is to fall back on the older view that nuclear weapons obviate the need for a mass army intended to take on a peer like Russia. Indeed, the new Military Programming Law emphasizes the critical place of nuclear deterrence in French strategic thinking. France also presumes, still, that in such a fight it would not be alone, hence Macron’s insistence on a broader European defense effort in parallel with earnest commitment to NATO integration.

France, it seems, is staying the course. This means it will have a top-tier high-end military that would be able to dance around Russian forces, but not for long. What happens then will most likely depend on the United States and the rest of NATO, and the question of whether nuclear deterrence will prove its worth.

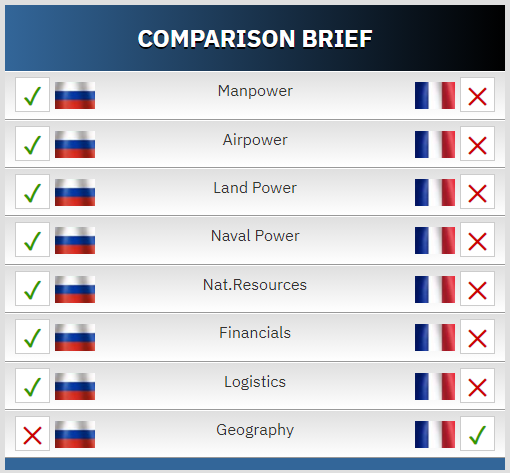

Side-by-side comparison showcasing the relative conventional fighting strengths of Russia and France for the year 2024:

Why ‘Geography’? Something needs to be better)))

Fig. globalfirepower.com

It’s all very interesting? But Russia doesn’t have any plans to fight with Europe as they many times said. Stop intimidating the world with contrived Russian aggressiveness.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:07 23.04.2024 •

12:07 23.04.2024 •