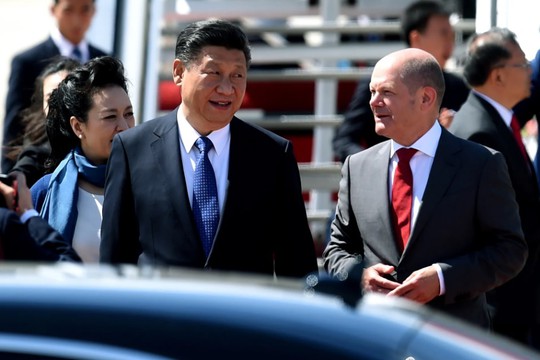

Xi and Scholz during previous visit.

Photo: AFP

Ignoring pressure from Washington, chancellor seeks Beijing’s embrace. With the next national election just over a year away, the leader of Europe’s sputtering economic engine is running out of time to conjure a miracle and reverse his government’s calamitous standing with the German population, notes POLITICO.

Scholz's three-day visit to the Middle Kingdom, which has began Saturday, will be both his longest and most important foreign trip since he assumed office in late 2021. For the chancellor, beset by record-low approval ratings and a fractious coalition, the tour is an opportunity not to just prove he has global standing, but to show voters he'll do whatever it takes to preserve Germany, Inc. — Zeitgeist be damned.

Even if German leaders never tire of reminding the world of their devotion to the highest moral standards, Berlin has proven time and again that it isn’t willing to sacrifice its prosperity on the altars of human rights, Washington’s security concerns or even the European Union.

For decades, the road to China was paved with gold for German exporters, padding their profits and maintaining Germany's position as one of the world's top-tier economies.

More recently, though, that road has looked more like the highway to hell amid Beijing’s ever-more aggressive protectionism and heavy-handed industrial policy…

Meanwhile, the European Union is increasingly frustrated by the generous subsidies China provides its key industries, from wind turbine makers to auto companies. A flood of cheap Chinese electric vehicle imports into Europe is pressuring local manufacturers to such a degree that Brussels is weighing imposing tariffs as soon as the summer.

In other words, there's no going back. When German industry first moved into China in the 1980s, politicians and executives believed they were investing in the future. With prosperity, China would liberalize and become more Western, democratic even.

For German companies such as Siemens and Volkswagen, which began investing in China 40 years ago, the country is now a pillar of their global business. China accounts for about 50 percent of VW’s global car sales alone.

While Germany’s biggest companies — the auto companies and chemical makers such as BASF — are the most exposed to China, many of their suppliers have also made big bets on the country.

"Trade with China brings us prosperity and is practically irreplaceable in the short term,” said Moritz Schularick, the President of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

After a lackluster 2023, economists and the International Monetary Fund expect the German economy to continue to stagnate. Exports are down more than 2 percent so far this year with no signs of relief on the horizon. Though German employment remains robust, that could change quickly if the economy doesn’t pick up.

While Germany faces a laundry list of growth challenges, from a chronic shortage of skilled workers to overregulation, what some economists see as most crippling is the negative sentiment among businesses and consumers.

“It’s as if the German economy is paralyzed,” said Timo Wollmerhäuser, an economist with the Munich-based Ifo Institute, one of Germany’s leading economic think tanks. “The mood is poor and insecurity is high.”

Against that backdrop, Scholz’s China trip carries more than a hint of desperation. Even if China were to open its doors to more foreign competition and halt its price dumping practices in Europe, the Chinese economy is not the growth powerhouse of yore. A property crisis and overcapacity in key sectors have left China's economy on the ropes.

More worrying for Germany is that China no longer needs the machinery and other highly engineered capital goods that drove German export growth to the country in recent decades. That’s not just due to weaker demand; Chinese companies have largely caught up with their German competitors, making the country less dependent on imports.

A major break with China would shrink the German economy by about 5 percent, according to a recent study by the Kiel Institute, on par with the downturn Germany experienced in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID pandemic. In other words, it would be brutal, not fatal.

“Our country has enough resilience to manage even such an extreme scenario," Kiel's Schularick said.

Braving that storm is easier said than done, however. What’s more, Scholz can ill afford afford a further erosion of Germany’s business links with China at a time when his country’s economy is already struggling.

German industry is already heavily invested the U.S., which is by far the country’s largest export market (German exports to the U.S. totaled €158 billion in 2023 alone, compared to €97 billion to China). On paper, China (Germany’s biggest trading partner when combining exports and imports) would appear to be the market with more growth potential.

Germany’s reliance on the U.S. for its security means it may have no choice but to acquiesce to American pressure to turn away from China if push comes to shove. But so far, Scholz, like Angela Merkel before him, has succeeded in juggling the two relationships.

Lucky for Scholz, there’s no German word for “de-risk,” which may explain why no one wielding real power in Berlin seems to take the idea seriously. The government's much-ballyhooed strategy paper occupied Berlin's China-focused think tankers for months, but it turned out to be little more than a 64-page paper tiger.

Back in the real world, Germany industry has not only not reduced its engagement with China, it's going for broke. German direct investment in China reached nearly €12 billion in 2023, a record. The Germans invested more in China between 2021 and 2023 than in the five-year period between 2015 and 2020, according to IW Köln, a leading economics institute.

The highlight of the trip for Scholz comes on Tuesday with a lengthy audience with Xi.

Despite its waning economic standing, Germany remains a key prize for China, both due to its weight in the EU and its close ties to the U.S. A return of Donald Trump to the White House next year would present Xi with a golden opportunity to woo Berlin with the promise of closer economic ties, POLITICO concludes.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:47 16.04.2024 •

11:47 16.04.2024 •