There’s been talk by the US for over a decade already about a so-called “New Middle East”, a vague concept which was never officially described by American officials yet has been heavily speculated upon by the expert community, both within the country and abroad. The generally accepted concept has grown from one of an American-emulated “Western democratic” Middle East to a partial undeclared revision of the Sykes-Picot Agreement which gave the region its contemporary political borders, though the election of Donald Trump might herald in a rethink of American grand strategy in this regards.

It’s pertinent at this important point in time to therefore assess the theoretical development of the US’ approach to the “New Middle East”, taking into account the three main International Relations theories and their practical application to American policy. The research will thus begin with an overview of neorealism, neoliberalism, and constructivism in order to remind the reader of their relevance. Next, the second part will take a look at how this worked out across the Bush and Obama years. Finally, the last section of the research will elucidate on the author’s personal analytical insights in arguing that American policy towards the Mideast has hitherto been defined by the failed experimental practice of neorealist-constructivism for neoliberal ends.

Theoretical Backgrounder

Neorealism:

The first school of international relations thought that will be discussed in the dissertation is neorealism, which has played an outsized role in influencing the formation of US policy towards the Mideast. The godfather of this method of analysis is Kenneth Waltz, a famous US political scientist who published the groundbreaking book “Theory Of International Politics”[1] in 1979. This book is universally regarded as one of the most important pieces of literature ever released in field of international relations, and it resulted in Waltz being recognized as the founder of this theory. Neorealists adopt a structural approach to International Relations, in that they first examine how the international system functions and then proceed to analyze everything else from there. Waltz wrote that the world is defined by the state of anarchy, meaning that there is no ultimate deciding force that’s keeping everything together and enforcing rules. He says that this is a self-help system and that states can only depend on themselves to defend their interests. Therefore, he concludes, anarchy is the ordering principle of the international system, which thus makes it the defining feature of International Relations.

Proceeding from this fundamental understanding, Waltz infers that while anarchy indeed impacts on every form of international behavior, that there are still certain patterns and sets of constraining conditions that lead to the formation of some vague semblance of order. One of the most relevant of these is the concept of hierarchy. David A. Lake wrote in his book “Hierarchy In International Relations”[2] that this means that powerful states take advantage of weaker ones, and that this has been happening for millennia already, whether it was carried out through empires, tributary systems, hegemonic orders, spheres of influence, or any other sort of construction. In the modern day system of international relations, Lake says that this makes some states subordinate to the US while others resist its power. Ultimately, he summarizes that hierarchy is a voluntary system of contacts between states, but one which is still fully influenced by the systemic constant of international anarchy. To refer back to Waltz and his pioneering “Theory of International Politics” treatise, hierarchy is affected by the distrust that states feel towards one another --- a condition emblematic of international anarchy – and that larger states balance while others bandwagon.

Balancing, Waltz believes, occurs when states modify their domestic and international policies in order to compete with one another, while bandwagoning is typically exemplified by smaller states teaming up to confront a larger one (which they perceive as being above them in the hierarchic scale). The inadvertently spiraling distrust that balancing and bandwagoning produces in states leads to what is termed as the security dilemma, which can be concisely described as the unintentional escalation of distrust and competition that occurs between states when one takes actions that it believes to be defensive but which are perceived by their international peers as offensive, thus catalyzing a cycle of more balancing and bandwagoning. The reason why states behave this way is because they crave power and see this as irreplaceable in guaranteeing their survival, which is what all states’ most basic interest is. Every state, Waltz writes, behaves in a rational way, and while there are veritably other actors that partake in influencing international affairs, states are the only ones that really matter because they’re the most powerful. He then logically postulates that if all state are rational, then they will always pursue what they believe to be their national interests, which is a subjectively defined term that varies from state to state. The contradiction between national interests results in rivalry, which in turn inspires states to make moves against the other in correcting the perceived imbalance between them.

The complicated maneuvering between states when they engage in balancing and bandwagoning could interestingly result in a sort of normalcy and stability in the international system, which is regarded by scholars as being the Balance of Power Theory. Alexei Zobnin does an excellent job of explaining what this entails in his 2014 article about “Balance of Power Principle Revisited”[3]. He says that strong states will both internally and externally balance against their perceived rivals in order to maximize their power in the anarchic international system and preempt any possible threats against them. Although this is theorized as bringing balance to the global order, Zobnin disagrees, citing various contradictions which he argues disprove this assertion. Despite that, the Balance of Power principle is popularly regarded as one of the main anchors of neorealist theory and is generally very accurate in making sense of the actions that Great Powers engage in most of the time. Renowned expert John Mearsheimer writes in his 2013 article about “Structural Realism”[4] that states engage in either offensive or defensive realism. He describes the first as essentially being ‘power for the sake of it’ and the only perceived means with which the state believes that it can guarantee its own security, which aptly sums up why aspiring hegemons behave the way that they do. As for the second form of realism, this accounts for the bandwagoning which was just described.

In speaking about the back-and-forth dynamics between different groups and categories of states, when there are multiple centers of power, the international system can be said to be multipolar and unpredictable, but when there are two like during the Cold War, for example, then it becomes bipolar and stable. This is yet another theoretical supposition related to neorealism. The most radical manifestation of this school of International Relations comes from those who ascribe to the Hegemonic Stability Theory, which states that unipolarity – the international condition in which a single hegemon exerts predominant power all across the world – is the most stable and preferable type of ordering system for preserving peace in an anarchic system. The neoconservative faction of the American elite, a mainstay of the US’ permanent military, intelligence, and diplomatic bureaucracies who gained widespread prominence during the Bush Administration, pertinently adhere to this dogma. David Skidmore cites the Hegemonic Stability Theory in his 2010 book about “The Unilateralist Temptation in American Foreign Policy”[5] in declaring that that it “suggests that the hegemon should embrace multilateralism during its period of ascendance but shift toward unilateralism as relative decline sets in”. This is an accurate depiction of the US’ 1990s unipolar moment during which it sought to multilaterally engage as many partners as possible in pursuit of its ends, and it also describes the post-9/11 unilateralism of the Bush Administration very well too.

Neoliberalism:

The rival school of neorealist interpretation is neoliberalism, the origins of which are also nearly four decades old. Robert Keohane is credited with introducing this theory to the world in his 1984 book “After Hegemony”[6], which has gone on to be cited as the main neoliberal text. Just like Waltz and the neorealists, Keohane recognizes that anarchy is pervasive in the international system, but his divergence with their ideas begins when he proposes that it’s possible to maintain a sort of order amidst this chaos if states join the same international regimes. Institutions, Keohane writes, are the key to preserving peace in the anarchic world, arguing that the shared self-interests that unite each of the members reinforce their desire to cooperate with one another. Institutions are so important because they have clearly established rules, commitments, and stakes that each party must abide by in order to collectively attain their self-interests. Modern-day theorists have expanded on this point to posit that democracy could serve as an ends in and of itself by being its own institutional form dedicated to peace. Proponents of this ideology advocate the spreading of democracy all across the world out of the belief that democratic states don’t go to war against one another, which is central tenet of the Democratic Peace Theory.

The neoliberals emphasize the role that national policies, concessions, and deal-making play in moderating anarchy, but they seem to neglect the importance of power and national interests when analyzing International Relations. This shortcoming is a common criticism of neoliberals, who are sometimes accused of being too utopian in their viewpoints. On the other hand, their system of analysis is useful in filling in the blind spots that neorealism fails to address, which is why Waltz’s work came first and was followed by Keohane’s, and not vice-versa. Looking at the applicability of neoliberalism to the formation of the US’ foreign policy towards the Mideast, it’s clear to see how influential this strain of thought was in shaping strategists’ thinking. After all, one can convincingly argue that the origins of democracy promotion rest with Keohane, and that the neoconservatives adopted some of these ideas into their worldview. Taking this even further, it almost looks like the neoconservatives believe that the Hegemonic Stability Theory could best be served by promoting the Democratic Peace Theory, or in other words, that they believe that unipolarity could be upheld by a combination of neorealism and neoliberalism. This conclusive point is important for the reader to keep it in mind when reviewing the rest of the neoliberal theory.

More insight needs to be given about the specifics of the Democratic Peace Theory and the influence that it’s had on neoliberal thought, so it’s appropriate to cite 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant’s 1795 “ Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch”[7] in tracing the roots of this idea. Kant is regarded as the godfather of liberalism and he advocated a community of democratic nations as the most surefire guarantee of global peace, which obviously is the Democratic Peace Theory in everything but name. Paul K. Huth and Todd L. Allee attempted to prove the validity of this theory by analyzing the entire 20th century in their 2002 book “The Democratic Peace and Territorial Conflict in the Twentieth Century”[8]. This lengthy work references numerous data points and a plethora of case studies in striving to prove that the theory is reputable and does in fact account for prolonged periods of peace between democracies.

The Democratic Peace Theory isn’t infallible though, and it obviously remains a theory and not a political law because it can’t be conclusively proven as a determinant of system behavior. Toni Ann Pazienza worked hard to expose the limits of this idea in the 2014 work “Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - The Role of US-China Relationship”[9]. The researcher writes that there are serious questions about the frame of reference that constitutes a “democracy”, as well as what is meant by “war” or “conflict”, pointing out that “democracies” might actually be more violent than non-democracies in that they often go to war against the latter. Moreover, the Democratic Peace Theory doesn’t provide for modern-day forms of non-traditional aggressions such as information and economic wars, and this, the realistic critics claim, proves that it’s impossible to indefinitely sustain a lasting peace between any two states.

The most radical expression of neoliberal theory is probably the modern-day ideologues who obsess over the idea of militant “democracy promotion”, “humanitarian interventionism”, and “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P). It’s clear to see the connection between the Democratic Peace Theory and Bush’s “democracy promotion” in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as Obama’s clandestine support of this during the “Arab Spring” theater-wide Color Revolutions, so this doesn’t necessarily need any further elaboration. As for the latter two, it’s useful to point out that they’re the cusp of this ideology in the present day and serve as its operational motivation in certain cases. Former US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power released a highly influential publication about “humanitarian interventionism” in 2002 called “A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide”[10], in which she makes the case that the US – as the unipolar global hegemon that it is – has a moral duty to intervene in foreign conflicts in order to stop genocide and ease the humanitarian suffering on the civilian population. According to the UN’s official website[11], R2P grew out of the 1990s concept of “humanitarian interventionism”, and it can be defined as the responsibility that the international community has to prevent genocide or the threat thereof. Understandably, it’s inferred that the promotion of democracy in the targeted state would follow the encouraged military intervention, thus connecting these two theories to their neoliberal Democratic Peace Theory roots.

Constructivism:

At this point, it’s worthwhile to reference the words of Stephen M. Walt[12] in reminding the reader of the need to maintain a balanced analytical understanding of international events and to avoid depending too much on one or the other paradigms. When analyzing any country’s foreign policy, let alone the US’ in the Mideast, one must always keep in mind that the theories and their related conclusions function merely as instruments inside the toolbox of understanding for each unique case-by-case scenario. The neorealist models that make the most sense in explaining the 2003 Invasion of Iraq aren’t necessarily relevant for analyzing the 2011 “Arab Spring”.

On the surface of things, it appears astoundingly difficult that a consistent framework could ever be presented in explaining the general theory of the US’ Mideast policy, which is why it’s necessary to introduce the third paradigm of International Relations thought into the equation in explaining how it’s possible that the US could regularly oscillate between two fundamentally different models of behavior. That ‘x-facto’ is constructivism, which was first articulated to the world in Alexander Wendt’s 1999 book “Social Theory of International Politics”. This was the first time that social theories were introduced to International Relations, hence the title, and the academic made a point of speaking out against the presumed universalism that he argued doomed the other two theories into partial relevance.

Instead of analyzing the world from a structural top-down perspective, Wendt opted for a ‘bottom-up’ one which incorporated intangible internal dimensions such as ideas, perceptions, and norms. He said that these shape the behavior of states, and that anarchy is relative to what states make it out to be. It doesn’t have to be an egotistical self-help system and zero-sum scramble that the neorealists make it out to be, but could just as equally be the cooperative system that the neoliberals purport is possible, and vice-versa. The key differentiators, Wendt says, are ideas, perceptions, and norms, and if these are shared, then neoliberal cooperation is possible; if they aren’t, then neorealist competition and conflict ensue. What it all essentially comes down to are identities and the means through which they’re shaped. Constructivists think that these are the most important determining factors, even more so than power and interests.

With this added insight in mind, it’s now possible to move towards building an inclusive theory about the US’ Mideast foreign policy which accounts for the neorealist and neoliberal variations that the US practices in this regard, as well as explaining its seemingly incomprehensible behavior between the past two administrations. The 1992 Wolfowitz Doctrine[13] greatly aids in these efforts by framing the US’ post-Cold War foreign policy in the neorealist perspective of upholding the Hegemonic Stability Theory and unipolarity. Then-Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, writing on behalf of the exuberantly ‘victorious’ US “deep state” apparatus shortly after the end of the Cold War, described how it’s absolutely imperative for the US to take any and all steps necessary to preempt the rise of any forthcoming regional power which could rival Washington’s power anywhere across the world.

In practice, the Wolfowitz Doctrine influenced the US to perceive of all states as being part of a zero-sum power game and having a unique role to play, which in turn was elaborated upon by Zbigniew Bzezinski in his 1997 work about the “Grand Chessboard”[14]. The US’ goal is to either co-opt or control all states in the world in order to bring them into Western-led institutions, from where they could then be subordinated, neutralized, and redirected as weaponized chess pieces against the remaining players, taken in this case to be Russia, China, and Iran. As the US strives towards this megalomaniac goal, it is invariably placed in circumstances where its decision makers and strategists see an advantageous desire to engage in regime change.

The US promotes regime change through one of two ways. The first one is direct and in accordance with the neorealistic model of direct state-on-state force, but this is costly in terms of both personnel and finances. The most prominent example is Iraq, but Panama and Grenada are two smaller-scale ones where a conventional regime change military invasion didn’t result in a total war against the population. On the other hand there’s the indirect model which follows the neoliberal theory. The concept here is to use diplomacy to gradually promote the long-term transformation of the targeted state, such as like what the US is presently employing in regards to Iran, Cuba, and Myanmar. The problem, though, is the timeframe, which might not be sufficient for some decision makers who might think that the matter at hand is much too urgently pressing to potentially dilly dally around for decades.

This is where the constructivist approach to regime change becomes the most applicable. Instead of large-scale invasions or years-long investments of diplomacy and economic coercion, the US works on inciting identity conflict in geostrategic states by using the asymmetrical means of information warfare, NGOs, and mercenary collaborators, all of which merge together in the field to instigate what are now known as Color Revolutions. The transition from a failed Color Revolution to an Unconventional War – such as what was visibly witnessed in Libya and Syria – can be defined as “Hybrid War”[15], which characterizes Obama’s foreign policy in the Mideast.

The constructivist implementation of regime change aims to introduce systemic shocks to the targeted national framework that thus make the victimized government either easier to topple in line with the neorealist perspective (whether by direct US intervention like in Libya or indirectly through proxies like in Ukraine) or easier to coerce through neoliberal paradigms (such as the intensified UNSC anti-Iranian sanctions that the US introduced after the failed 2009 ‘Green Revolution’). In what should be a thought-provoking observation for all curious International Relations researchers, constructivism might not just be the ‘glue’ that bridges the neorealist-neoliberal divide in American foreign policy (including its interlinked regime change and US Mideast foreign policy manifestations), but could actually be a lot more deserving of study as its own independently acting paradigm of understanding. This is because the emphasis that constructivism gives to identities and perceptions is ever more important in the present-day accelerated era of information-globalization, with the observable consequences being the regularity of intra-state conflicts since the end of the Cold War, especially in the Mideast following the “Arab Spring”.

Observations And Facts

American Policy Before 9/11

The US’ policy towards the Mideast changed after the end of the Cold War in 1989. By the time the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, the US had already launched its first large-scale military intervention in the region, Operation Desert Shield. In the 10 years between this operation and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the US developed the foundation for its contemporary Mideast policy.

Immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US military drafted a policy promoting unipolarity and the country’s sole superpower status. The basic concept behind all of America’s post-Cold War military actions was envisioned to “prevent the emergence of a vacuum or a regional hegemon”[16]. The document’s drafting was overseen by Paul Wolfwitz, who was then the Under Secretary of Policy for the Pentagon. The idea, as Wolfowitz advocated, is to prevent the emergence of any regional hegemon anywhere in Eurasia, be it Russia, China, Iran, or others. One of the best ways to accomplish this, especially if all else fails, is to take advantage of what he terms the “Eurasian Balkans”. There is an entire chapter in Brzezinski’s book dedicated to explaining this concept, but in short, the idea goes that a large space of Eurasia stretching from “southeastern Europe, Central Asia and parts of South Asia, the Persian Gulf area, and the Middle East” is even more volatile than the powder keg Balkans of the early 20th century but extremely rich in natural resources. This area is identified as integral to control and influence, but its fracturing can also be manipulated to prevent the emergence of a regional hegemon and to cement American influence over Eurasia. In a reverse way, the vacuum that Wolfowitz warned about can be used to prevent any competitors to American primacy and can secure the unipolar world.

To mention a few words about Zbigniew Brzezinski, he was the former National Security Advisor to Jimmy Carter and has been a mainstay political advisor to successive presidents since then. He wrote “The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives” in 1997. In an allusion to the Wolfowitz Doctrine’s application in the Eurasian landmass, he advises that ''If the middle space can be drawn increasingly into the expanding orbit of the West (where America preponderates), if the southern region is not subjected to domination by a single player, and if the East is not unified in a manner that prompts the expulsion of America from its offshore bases, America can then be said to prevail. But if the middle space rebuffs the West, becomes an assertive single entity, and either gains control over the South or forms an alliance with the major Eastern actor, then America's primacy in Eurasia shrinks dramatically.''[17]

Although Brzezinski’s geopolitical recommendations bring into doubt whether or not the US is opposed to the emergence of a “vacuum”, nevertheless, the idea of stultifying regional hegemons and “convincing potential competitors that they need not aspire to a greater role or pursue a more aggressive posture to protect their legitimate interests” (even if military, covert, or regime change means must be used to achieve this) have remained the hallmarks of American foreign policy. Importantly, future Vice President Dick Cheney was occupying the post of Secretary of Defense at the time that the Wolfowitz Doctrine was promulgated and most certainly would have been influenced by it (if not directly involved in its publication himself).

After Wolfowitz and Brzezinki’s ideological contributions to regime change, an institutional development took place through the creation of the neo-conservative Project for a New American Century (PNAC) think tank by Dick Cheney in 1997. As noted by Democratic grassroots organization “Move On” in a special investigative report bulletin released in 2003, PNAC exercised enormous influence over the Bush Administration not least through the inclusion of some of its members into the administration (Bolton, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz)[18]. It is alleged that they played a disproportionate role over influencing the Iraq War. In fact, this group of individuals had actually been pushing for a war in Iraq since 1998. Antiwar.com’s Bernard Weiner also explored the influence of PNAC in 2003, and he writes that they unsuccessfully tried to lobby for regime change there prior to the punitive Operation Desert Fox[19].

Move On’s report bulletin also reported that a few of the PNAC members that they listed participated in a Foreign Policy in Focus Forum about Syria’s role in Lebanon. The participants all signed a statement where it was recommended that the US begin planning for military action against Syria because “if there is to be decisive action, it will have to be sooner than later”[20]. Later that year in September, PNAC published a report entitled “Rebuilding America’s Defenses”, in which it was stated that "Over the long term, Iran may well prove as large a threat to U.S. interests in the Gulf as Iraq has.”[21] The Wolfowitz Doctrine explicitly forbids the emergence of any regional hegemon that could challenge American predominance, so in this instance, Iran was already being identified as a target by the same influential think tank organization which would later exert a strong effect on US foreign policy during the Bush years, when regime change was wantonly planned and applied across the world. It is thus no coincidence that in Hersh’s “The Redirection” article, he explains the US’ destabilization campaign against Syria as being launched on the grounds of rolling back Iranian influence by proxy[22].

Following the creation of the PNAC, the next regime change step in the US prior to 9/11 was the 1998 Iraq Liberation Act. This piece of legislation was already mentioned in the preceding chapter, but its inclusion is once more pertinent in explaining the development of contemporary American foreign policy towards the Mideast. This Act stipulated that the US would officially begin going about regime change in Iraq, which incidentally happens to be located right at the heart of the geostrategic Mideast. It is also perfectly positioned to be in the middle of Brzezinski’s Eurasian Balkans. If one wants to control or fracture the Eurasian Balkans in order to promote American hegemony over both continents, there is no better place to start than in Iraq.

The Reconceptualization of the US’ Mideast Policy:

The 9/11 terrorist attacks provided the justification for the US’ Global War on Terror. This involved unilateral military incursions into the Muslim world. To adapt to this military reality, a reconceptualization of the Mideast occurred among the US’ foreign policy planners.

The CIA World Factbook offers a somewhat traditional meaning of the Mideast. It includes all of the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, the Caucasus, Turkey, and the land in between[23]. Notably, Egypt is not included in its definition, although it typically is understood as being incorporated into this region (whereas the Caucasus are not). Nonetheless, this source provides the closest authoritative definition as to what traditionally encompasses the area of study.

In April 2004, the US unveiled a strategy called the Greater Middle East Initiative. The Brookings Institute wrote at the time that this region “stretches from Morocco to Pakistan”[24], thus amounting to the incorporation of all of North Africa, the entire traditional Middle East, and parts of South Asia. The purpose behind expanding the definition of the Mideast was ostensibly to promote region-wide democratization, according to the report. The expansion of the region’s defined scope is important because it will set the stage for the US’ theater-wide strategy, including the “Arab Spring” regime change events.

The next evolution of the US’ reconceptualization of the Middle East was the characterization of a “new Middle East” by Bush’s Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice in July 2006 when she was addressing the ‘Israeli’ invasion of Lebanon. She said that “What we're seeing here, in a sense, is the growing -- the birth pangs of a new Middle East. And whatever we do, we have to be certain that we are pushing forward to the new Middle East, not going back to the old one.”[25] This statement proved that the US had designs for a new Mideast political arrangement and that it also had an interested stake in this outcome.

Combining the two re-conceptualizations of the Mideast together, one can see a patterned US approach towards the region. First, the US delineated the scope of its politically transformative activities (the Greater Mideast), and then it set about working with its allies (in this context, ‘Israel’) to change the facts on the ground and bring about its intended changes (the New Middle East). This New Greater Mideast is envisioned as being radically different than the old one, and the details of this plan will be described shortly.

The US had a specific vision in mind for this New Greater Mideast, and it would have to resort to the strategy of geopolitical engineering in order to achieve this. This means that the US sees its role as transforming the facts on the ground in order to usher in a new regional reality. It will be proven that this objective was the pinnacle of the US grand strategy in the Mideast and that regime change plays an integral role in reaching it.

Famed American military leader, the commander who oversaw the War on Yugoslavia, and the former Supreme Allied Commander of Europe for NATO General Wesley Clark published his memoirs in 2007. He recounts shocking details which prove that the US decided to implement regime change against a plethora of Muslim governments in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, likely indicating that they had been plotted long before that. Clark recalls how two weeks after 9/11, a “senior general” told him, “We’re going to attack Iraq. The decision has basically been made.”[26] Even more stunning, he writes that this same general told him six weeks later that “‘Here’s the paper from the Office of the Secretary of Defense [then Donald Rumsfeld] outlining the strategy. We’re going to take out seven countries in five years.’ And he named them, starting with Iraq and Syria and ending with Iran.”

Salon magazine investigated previous statements by Clark to piece together the other countries, which they identified as Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, and Sudan. Every single one of these countries would go on to experience different degrees of American-directed destabilization, with some of them successfully having their governments overthrown. This confirms that the American government’s decision to illegally topple the legitimate Syrian leadership was long in the making, stretching back to at least this point of time in October 2001.

The Expanded “Axis of Evil”:

The next development that occurred in order to promote regional regime change in the Mideast was the creation of the “Axis of Evil”. Bush grouped Iraq, Iran, and North Korea into this category during his January 2002 State of the Union address before expanding it to Cuba, Libya, and Syria in May of 2002[27]. Not coincidentally, it was PNAC member John Bolton, then serving as Under Secretary of State, who made the announcement that de-facto placed Syria on the official regime change agenda. It is appropriate at this point to recall that some PNAC members had signed a statement advocating military force against Syria after a forum on the topic in 2000. This shows that the conspiracy against the country can directly be traced back to that point, even if it was not official American policy at the time.

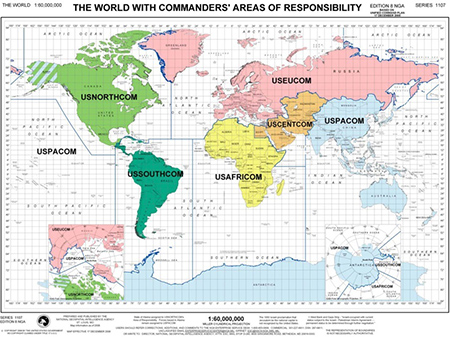

Speaking of the expanded “Axis of Evil”, it serves a certain military-political purpose for decision makers. US Central Command (CENTCOM) is the Department of Defense’s entity tasked with overseeing military operations in part of the Greater Mideast: [28]

As can be seen from the above map, the “Axis of Evil” linkage between Syria, Iraq, and Iran forms a clear-cut contiguous line perfectly dividing CENTCOM in half. This means that the US may have found it convenient to target all three countries for regime change because this would allow its military command (CENTCOM) to multiply its force potential in its highlighted regional theater.

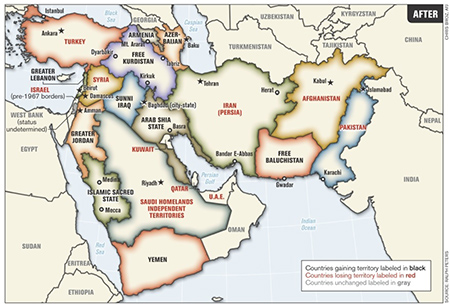

In June 2006, Army Lt. Col. Ralph Peters hypothesized “How a better Middle East would look” in the Armed Forces Journal article “Blood Borders”[29]. He proposed a complete restructuring of the region, with almost every country experiencing either an addition or a loss of territory. His map is below: [30]

It can be seen that this is likely what Condoleeza Rice had in mind when she referred to the “New Middle East”. Whether by coincidence or not, she evoked that term one month after Peters’ article was published. Pertaining to Syria, it is planned that the country loses its Kurdish part (mostly Al-Hasakah Governorate) to “Free Kurdistan” and that Latakia and Tarus Governorates be incorporated into a “Greater Lebanon”. Therefore, not only is regime change on the table for Syria, but so too is dismemberment.

It must also be pointed out that Seymour Hersh’s article “The Redirection”[31] is relevant to proving the thesis at hand. In this reference, it continues the chronology of the US regime change strategy against Syria that was just described. It shows that there was a definitive leap from strategy and planning towards action and destabilization, and that 2007 can mark the earliest reported confirmation that the US had activated its plan (albeit in a ‘soft rollout’) to overthrow the Syrian government.

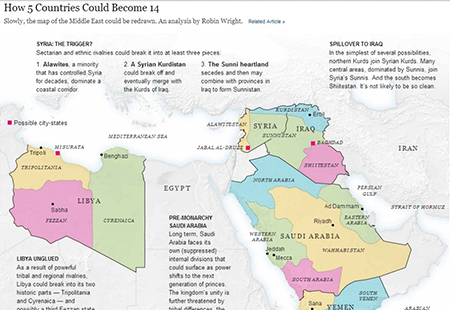

Moving along, The New York Times published a provocative infographic in September 2013 after the threat of a US war in Syria had died down. It can be considered the adapted spiritual successor to Peters’ Blood Borders because it also proposes a radical redivision of the Mideast’s borders, even suggesting that Syria may be the trigger that initiates the entire process: [32]

The fact that such a concept is still being discussed shows that the idea is deeply ingrained in American foreign policy thinking. Additionally, unlike Peters’ article, this political revisionist thinking has made the jump from academia to mainstream, thereby showing that there is a strong push to have this idea accepted by the general population.

Although similar in that they envision a mangled Mideast, the Blood Brothers article and the NYT piece see a slightly different future for Syria. Peters’ 2006 work still sees Syria remaining as a country, albeit in a reduced form after “Greater Lebanon” and “Free Kurdistan” dislodge themselves from the unified state. The situation is different with the NYT. They see Latakia, Tartus, and the western fringes of Syria becoming “Alawitestan”, whereas the northern edge and the northeast join together to create “Kurdistan” and unite with their Iraqi brethren. “Syria” no longer exists in this model, since the authors join it with the Sunni portions of Iraq (which also no longer exists in their map) to form “Sunnistan”. Interestingly, unlike Peters’ scenario, the NYT’s 2013 map does not show “Kurdistan” as encroaching into Turkish territory, where the majority of that ethnic group live. This could be political payment for Turkey’s contribution in destabilizing Syria in the years since Peters’ article was published.

Syria:

In 2005, the Cedar Revolution occurred in Lebanon, resulting in a change of government and a drastic change in relations with Syria. The pretense for this de-facto Mideast Color Revolution (proto-“Arab Spring” rehearsal) was that the Syrian government had been behind the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri. The result of this mass mobilization movement was the expulsion of the Syrian military from Lebanon, where they had been positioned since 1976 in trying to maintain the peace during and after the Lebanese Civil War[33], and a weakening of Damascus’ regional influence and ability to protect itself from a possible conventional ‘Israeli’ attack.

The situation is not as clear-cut as it was presented to the global audience, however. The investigative online journal CounterPunch examined all aspects of the Cedar Revolution to conclude that the Syrian government most likely had nothing to do with the assassination, and that the pro-Western and Western-funded NGOs active in Lebanon had carried out a Color Revolution to serve foreign interests[34]. This marks the first active American phase of the campaign against Syria. The objective was to sever ties between Lebanon from Syria (which it had formerly been a cultural and civilizational part of for centuries until the French dislodged it during their post-World War I occupation) in order to roll back and weaken Damascus prior to an even more intense destabilization designed to break it.

That moment eventually came with the theatre-wide Color Revolutions popularly known across the world as the “Arab Spring”, which sought to replace the region’s governments with Muslim Brotherhood proxies that would ultimately be loyal to their American patrons. The concept was to have this secretive clique rule over a transnational network of states which would in effect be one single political-ideological domain representing the first practical iteration of the “New Middle East” vision. That strategy completely failed, however, due to the heroic resistance of the Syrian people and the Syrian Arab Army, as well as 2013 military coup in Egypt which deposed Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi. Faced with a battlefield standstill in Syria, the US redouble its support for the terrorist groups (marketed as the “moderate rebel opposition” to international media) which would eventually form the basis for Daesh, Al Nusra, and other such Wahhabi death squads.

Throughout the six-year-long course of the War on Syria, the US appears to have concluded that the previously sacrosanct borders instilled in Sykes-Picot are subject to revision, as demonstrated by the previously cited New York Times article and other such sources of inference. American support for the Kurdish YPG militia in northern Syria is another such indication of their intent. Although Washington has publicly condemned this group’s illegal self-declared “federalization” and de-facto internal partition in their occupied territories, the US’ unwavering military backing of them suggests that their statements are simply a classic case of ‘plausible deniability’ in averting official blame for the far-reaching and predictably disastrous consequences of this strategy. President Trump, however, has voiced more of a realistic position on the Mideast and doesn’t seem to be in favour of any radical border revisions like his two predecessors hinted they were, so this brings cautious optimism that a fundamental strategic rethink might be in order.

Analytical Insights

Taken altogether, the case can be argued that Bush and Obama wanted to “democratize” the Mideast via the Western model, naively believing (or misleading the public to believe) that this would align with the Democratic Peace Theory in resolving the region’s many troubles once and for all. As the failure of Bush’s neoconservative state-on-state forceful policies became undeniably apparent, his successor and the permanent bureaucracy that he inherited looked to escape from the growing quagmire and improvise a solution which could still allow them to achieve their strategic ends. The divide-and-rule stratagem of Zbigniew Brzezinski was highly influential on the Obama Administration, and it sought to utilize the constructivist mechanisms of identity conflict in order to engineer a series of regime changes (the so-called “Arab Spring”) as a means of ushering in the “democratic” governments that Bush and his neoconservative backers originally envisioned.

As the War on Syria dragged on from the intentioned couple-week campaign to the over half-decade-long conflict that it’s presently become, the geostrategic revisionist ideas first prominently promulgated during the Bush Presidency once again came to the surface. American strategy had already morphed from one of “democratization” through external forceful means (the invasion of Iraq) to pursuing this same ultimate objective via internal mechanisms (the “Arab Spring” Color Revolutions), though the battlefield situation served to convince the US that this could only best be achieved through unofficially dismantling Sykes-Picot. The failure of the Muslim Brotherhood’s US-backed coups in the region resulted in the improvised backup plan of waging unconventional warfare on Syria, which in turn led to Washington countenancing the redrawing of the Mideast’s borders whether in legal or informal practice.

A clear pattern can thus be discerned, and that’s the employment of neorealist and constructivist means to advance a neoliberal objective, or in other words, the use of conventional state-based external and unconventional internal identity-based force to promote the eventual “democratization” of the Mideast. According to the Democratic Peace Theory, this would lead to the incorporation of the Mideast’s states (whether existing, rump, or newly formed ones) into the Western-dominated fold, thereby subjecting them to Washington’s transregional hegemony and prolonging its unipolar moment. As can be visibly evidenced, however, this theory dramatically failed owing to Russia’s anti-terrorist intervention in Syria and the steady rollback of American influence in the Mideast that followed, but the intent of the article wasn’t to argue that the examined theory is workable in practice, but just that it represented the intentions of the US during the past two presidencies.

The “New Middle East”, at least in terms of how it was previously conceived as a pro-American network of “Western democratized” Arab states, has now been debunked, though it’s plain to see that the region itself has dramatically changed ever since the 2003 Invasion of Iraq and 2011 “Arab Spring”. A new Middle East is indeed taking shape before the eyes of the world, but it doesn’t at all have to follow the precepts that the US originally laid out for it at the beginning of this century. Instead, there’s a very real possibility that President Trump might pull back from his predecessors’ neorealist-constructivist policies and rework the neoliberal end game objective in order to make the US’ strategy more pragmatic.

What is meant by this is that Trump, the consummate deal-maker, understands just how much of a drain the US’ seemingly never-ending wars in the Mideast have been for both the country’s finances and its global strategic flexibility, and in the ‘Pivot to Asia’ era where China is the most likely competitor to the US, it’s reasonable that Trump might try to cut Washington’s losses by progressively disengaging from the Mideast via a series of ‘face-saving’ gestures in order to focus more closely on the Asia-Pacific. If such an eventuality does indeed transpire, then it would represent the ultimate manifestation of realism in American foreign policy by embodying the hegemonic pragmatism exemplified by one of Trump’s key advisors, Henry Kissinger.

Now more than ever is the best time for the US to partake in a paradigm shift of policy towards the Mideast by reverting back to its realist roots and away from the constructivist hybrid that it’s been practicing over the past decade and a half. The pursuit of neoliberal ends is an inherently failed objective because recent history has proven that it’s not possible to accomplish this in a region as traditional and diverse as the Mideast, thereby repudiating the theoretical concepts underlying this disastrous strategy. Instead, what the US needs to do now at this crucial juncture is to pull away from the Mideast and concentrate more intensely on East and Southeast Asia, otherwise it’ll remain weakened by imperial overstretch and unable to suitably compete with China.

-----

References

"Background Information on the Responsibility to Protect." . United Nations, 2013. Web. 20 October, 2016. <http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/about/bgresponsibility.shtml>.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York, NY: BasicBooks, 1997. Print.

Conason, Joe. "“Seven countries in five years”." Salon Media Group, Inc. , 12 Oct. 2007. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.salon.com/2007/10/12/wesley_clark/>.

"Ending Syria's Occupation of Lebanon: The U.S. Role." . The Middle East Forum, May 2000. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.meforum.org/research/lsg.php>.

Hersh, Seymour. "The Redirection." . The New Yorker, 5 Mar. 2007. Web. 25 June 2014. <http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/03/05/070305fa_fact_hersh?currentPage=all>.

Huth, Paul K., and Todd L. Allee. The Democratic Peace and Territorial Conflict in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

John J. Mearsheimer, "Structural Realism," in Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith, eds., International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, 3rd Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 77-93.

Kant, Immanuel. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. New York: Liberal Arts, 1957. Print.

Keohane, Robert O. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1984. Print.

Korybko A. 2015. Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change. The People’s Friendship University of Russia. Available at: http://orientalreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AK-Hybrid-Wars-updated.pdf (accessed 07.12.216)

Lake, David A. Hierarchy in International Relations. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2011. Print.

Pan, Esther. "MIDDLE EAST: Syria and Lebanon." . Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., 18 Feb. 2005. Web. 27 June 2014. <http://www.cfr.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/middle-east-syria-lebanon/p7851>.

Pazienza, Toni Ann. "Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - The Role of US-China Relationship." Scholar Commons. University of South Florida, 25 Mar. 2014. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

Peters, Ralph. "Blood borders." Armed Forces Journal, 1 June 2006. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/blood-borders/>.

Power, Samantha. A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. New York: Basic, 2002. Print.

"Rebuilding America's Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources For a New Century." . Project for the New American Century, Sept. 2000. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/pdf/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf>.

Schuh, Trish. "Faking the Case Against Syria." . CounterPunch, 18 Nov. 2005. Web. 27 June 2014. <http://www.counterpunch.org/2005/11/18/faking-the-case-against-syria/>.

"Secretary Rice Holds a News Conference." The Washington Post, 21 July 2006. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/21/AR2006072100889.html>.

Skidmore, David. The Unilateralist Temptation in American Foreign Policy.Routledge, 2010. Print.

Taylor, Patrick E. . "1992 Wolfowitz U.S. Strategy Plan Document." The New York Times, 8 Mar. 1992. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://work.colum.edu/~amiller/wolfowitz1992.htm>.

"The CIA World Factbook: Middle East." . Central Intelligence Agency, n.d. Web. 26 June 2014. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/wfbExt/region_mde.html>.

"US expands 'axis of evil'." . BBC, 6 May 2002. Web. 25 June 2014. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/1971852.stm>.

Walt, S. M. (1998). One World, Many Theories. Foreign Policy, (110).

Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1979. Print.

Weiner, Bernard. "A PNAC Primer: How We Got Into This Mess." AntiWar.com, 2 June 2003. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.antiwar.com/orig/weiner6.html>.

Winer, Noah. "The Project for the New American Century." . MoveOn.org, 4 May 2003. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.moveon.org/moveonbulletin/bulletin13.html>.

Wittes, Tamara Cofman. "The New U.S. Proposal for a Greater Middle East Initiative: An Evaluation." The Brookings Institution, 10 May 2004. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2004/05/10middleeast-wittes>.

Зобнин, Алексей. "К ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЮ ПРИНЦИПА БАЛАНСА СИЛ ОПЫТ НЕОИНСТИТУЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ПОДХОДА К МЕЖДУНАРОДНОЙ СРЕДЕ." Международные Процессы (2014): 55-69. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

[1] Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub., 1979. Print.

[2] Lake, David A. Hierarchy in International Relations. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2011. Print.

[3] Зобнин, Алексей. "К ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЮ ПРИНЦИПА БАЛАНСА СИЛ ОПЫТ НЕОИНСТИТУЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ПОДХОДА К МЕЖДУНАРОДНОЙ СРЕДЕ." Международные Процессы (2014): 55-69. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

[4] John J. Mearsheimer, "Structural Realism," in Tim Dunne, Milja Kurki, and Steve Smith, eds., International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, 3rd Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 77-93.

[5] Skidmore, David. The Unilateralist Temptation in American Foreign Policy.Routledge, 2010. Print.

[6] Keohane, Robert O. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1984. Print.

[7] Kant, Immanuel. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. New York: Liberal Arts, 1957. Print.

[8] Huth, Paul K., and Todd L. Allee. The Democratic Peace and Territorial Conflict in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[9] Pazienza, Toni Ann. "Challenging the Democratic Peace Theory - The Role of US-China Relationship." Scholar Commons. University of South Florida, 25 Mar. 2014. Web. 20 Oct. 2016.

[10] Power, Samantha. A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. New York: Basic, 2002. Print.

[11] "Background Information on the Responsibility to Protect." . United Nations, 2013. Web. 20 October, 2016. <http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/about/bgresponsibility.shtml>.

[12] Walt, S. M. (1998). One World, Many Theories. Foreign Policy, (110).

[13] Taylor, Patrick E. . "1992 Wolfowitz U.S. Strategy Plan Document." The New York Times, 8 Mar. 1992. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://work.colum.edu/~amiller/wolfowitz1992.htm>.

[14] Brzezinski, Zbigniew. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York, NY: BasicBooks, 1997. Print.

[15] Korybko A. 2015. Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change. The People’s Friendship University of Russia. Available at: http://orientalreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AK-Hybrid-Wars-updated.pdf (accessed 07.12.216)

[16] Taylor, Patrick E. . "1992 Wolfowitz U.S. Strategy Plan Document." Op. Cit.

[17] Brzezinski, Zbigniew. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives. Op. Cit.

[18] Winer, Noah. "The Project for the New American Century." . MoveOn.org, 4 May 2003. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.moveon.org/moveonbulletin/bulletin13.html>.

[19] Weiner, Bernard. "A PNAC Primer: How We Got Into This Mess." AntiWar.com, 2 June 2003. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.antiwar.com/orig/weiner6.html>.

[20] "Ending Syria's Occupation of Lebanon: The U.S. Role." . The Middle East Forum, May 2000. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.meforum.org/research/lsg.php>.

[21] "Rebuilding America's Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources For a New Century." . Project for the New American Century, Sept. 2000. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/pdf/RebuildingAmericasDefenses.pdf>.

[22] Hersh, Seymour. "The Redirection." . The New Yorker, 5 Mar. 2007. Web. 25 June 2014. <http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/03/05/070305fa_fact_hersh?currentPage=all>.

[23] "The CIA World Factbook: Middle East." . Central Intelligence Agency, n.d. Web. 26 June 2014. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/wfbExt/region_mde.html>.

[24] Wittes, Tamara Cofman. "The New U.S. Proposal for a Greater Middle East Initiative: An Evaluation." The Brookings Institution, 10 May 2004. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2004/05/10middleeast-wittes>.

[25] "Secretary Rice Holds a News Conference." The Washington Post, 21 July 2006. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/07/21/AR2006072100889.html>.

[26] Conason, Joe. "“Seven countries in five years”." Salon Media Group, Inc. , 12 Oct. 2007. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.salon.com/2007/10/12/wesley_clark/>.

[27] "US expands 'axis of evil'." . BBC, 6 May 2002. Web. 25 June 2014. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/1971852.stm>.

[28] http://www.centcom.mil/ABOUT-US/

[29] Peters, Ralph. "Blood borders." Armed Forces Journal, 1 June 2006. Web. 26 June 2014. <http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/blood-borders/>.

[30] http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/peters-blood-borders-map/

[31] Hersh, Seymour. "The Redirection.", Op. Cit.

[32] http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2013/09/29/sunday-review/how-5-countries-could-become-14.html?_r=0

[33] Pan, Esther. "MIDDLE EAST: Syria and Lebanon." . Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., 18 Feb. 2005. Web. 27 June 2014. <http://www.cfr.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/middle-east-syria-lebanon/p7851>.

[34] Schuh, Trish. "Faking the Case Against Syria." . CounterPunch, 18 Nov. 2005. Web. 27 June 2014. <http://www.counterpunch.org/2005/11/18/faking-the-case-against-syria/>.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

23:26 08.08.2017 •

23:26 08.08.2017 •