At the end of September, the EU and Japan signed an agreement designed to add a new dimension to these two global economic powerhouses’ joint effort in the field of transport, energy and digital technology. This expansion of ties between the Old World and Japan is seen by Western media as a counterweight to, and even a pushback against China’s One Belt, One Road mega-project. What are the prospects of various projects dealing with the ongoing competition between transport corridors in Eurasia?

The EU-Japan rapprochement itself is symptomatic and by no means accidental. The efforts that the United States has been bending the past 2-3 years to unravel the existing international system, which in the course of the past decades has brought political and economic dividends primarily to the world’s most developed countries have intensified with the US also becoming increasingly self-serving, openly ignoring and even harming the interests of its nominal allies. As a result, the leading countries of Europe and Asia increasingly feel the need to strengthen the “global, multilateral order” that can solve problems that no country can solve on its own, from climate change to free trade [i] themselves, without the US.

Economic integration in Eurasia is just one such area. According to many leading German media outlets, “an expansion of the Eurasian trade zone bypassing the US-controlled shipping lanes spells a disaster” for America. [ii] To fend off this threat, Washington relies entirely on sub-regional projects, preferably under its own patronage. In the mid-2010s, the United States unveiled its conceptual vision of a future for the Asia-Pacific region, namely - the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and the New Silk Road initiative for Central Asia. In Europe, the US plans are primarily of a military- strategic nature, assigning for NATO the role of a re-integrator of the European continent in the event of an EU collapse. Simultaneously, the Trump administration persist with its attempts to drive a wedge between the EU’s western and eastern members by backing initiatives proposed by a number of Central-East European countries, and encouraging the development of local transport corridors and trade communities, leaning on the United States, instead of Europe, let alone Eurasia.

Meanwhile, European experts have been discussing the prospect of the EU leading the camp of supporters of maintaining liberal international trade standards as one of the best strategies for Brussels to go for. A similar view has been gaining traction also in Japan, which is increasingly suspicious of Trump's “crude protectionism” and arm-twisting in trade negotiations. And, adding to all this, are Washington’s new demands for increasing the cost of maintaining American troops. After the United States withdrew from negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Japan was one of the main proponents of keeping the talks going. No longer instrumental in the US efforts to “contain China,” a new-look TPP [iii] is able to more flexibly build its relations with the world’s second biggest economy, all the more so since China is viewed by almost all TPP participants as a key trading partner. Moreover, Japan is actively working on the implementation of the 15-sided [iv] free trade agreement in Asia and the Pacific, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), to cover half of the global economy [v], and where the US does not participate, while China does.

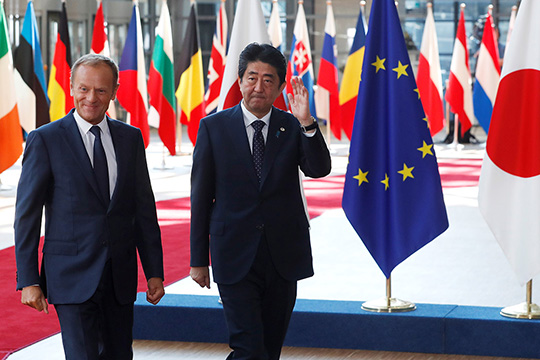

As part of this policy, the EU and Japan announced in July that they were setting up a free trade zone between them. And now, they have also signed an infrastructure deal to coordinate transport, energy and digital projects linking Europe and Asia. According to the leaders of Japan and the EU, this is about building up ties between the Indo-Pacific region and the Western Balkans and Africa, as well as setting up a sea route, "leading to the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean." However, infrastructure projects should not “create huge debts” and depend on “one country.” [vi]

But is the new Japanese-European “corridor” capable of becoming efficient without promoting partnership relations with other countries?

There exist various projects of economic integration in Eurasia - both between individual regions and those covering all or most of the regional states. Integration projects, such as the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Customs Union promoted by the Russian Federation are actively developing, both politically and economically. China relies on the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), which officially embraces most of the countries of Asia and Europe. Japan, for its part, has come up with a comprehensive strategy of Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, proposed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

In terms of the development of transcontinental transport corridors, Russia is in a favorable position. However, its transit potential for the development of trade between Europe and Asia is currently used at less than five percent of its capacity [vii]. Meanwhile, a sizeable share of infrastructure facilities in Eurasia (railways and highways) is oriented to Russia and which, according to RBC, can twice shorten the time of cargo traffic between Asia and Europe. In addition, Russia’s geographical position provides unique opportunities for optimizing existing transport corridors and creating new ones, in both meridional and latitudinal directions. And also for creating temporary and permanent corridors through a combination of rail, road and sea transport infrastructure. “The most promising transport corridors are the Northern Sea Route, the Trans-Siberian Railway and the North-South Corridor.” [viii]

Most recently, the Russian authorities finally approved plans for building a highway connecting China with Europe and running across Kazakhstan and Belarus. It is planned that hundreds of millions of rubles invested in this project within the next six years will help modernize and expand the transport routes that run through the territory of Russia and a significant part of the former Soviet Union, including the Arctic region. The highway will prove the viability of a project to successfully pair the Eurasian integration formats promoted by Moscow and Beijing with Russia’s national transport infrastructure modernization project. At the end of October, the head of Russian Railways, Oleg Belozerov, confirmed many leading German companies’ interest in participating in the construction of the St. Petersburg - Moscow - Nizhny Novgorod high-speed railway. [ix] Road and rail corridors can become the most cost-effective way of cargo shipment across Eurasia, replacing air transport, and in many cases, existing sea routes. According to the German newspaper Heise, Russia could become the center of the “Eurasian economic space stretching from Portugal to China” and consolidate it, “which can lead to a redistribution of power and to the isolation... of America.” [x]

Another promising long-term strategic project is the 7,200 km North-South International Transport Corridor (INSTC) to combine road and rail routes.

“It will connect the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf with the Caspian Sea through Iran, with subsequent access to Northern Europe via Russia.” [xi] At the end of 2018, it became known that Russia had released the first tranches of a credit line to finance INSTC. When speaking at the First Caspian Economic Forum in Turkmenistan, held in August, 2019, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev called INSTC “a promising area” that reduces by 2.5-fold the time of cargo delivery “from Europe via the Caspian to the Near and Middle East and further on to South Asia and back.” Russia’s long-term partnership with India, (which is the world’s fifth economy), and also with Iran and Azerbaijan, will play an important role here.

On the latitudinal plane, Russia offers potential partners a project for the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR). In the medium- and long-term period, commercial shipping along the NSR looks more and more attractive, because in some cases northern routes are between 1.5 and 2 times shorter than the main ones. The Chinese are already well aware of this, as they are promoting the concept of connecting the Polar Silk Road, which is designed to provide the People’s Republic with natural resources and alternative shipping routes for export, which, by 2020 will account for 5 to 15 percent of the country’s foreign trade volume [xiii], with the Russian NSR. Chinese investors have bought into a number of large industrial and infrastructure projects implemented by Russia beyond the Arctic Circle, including Yamal-LNG. According to Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, "China’s ambitions in the region do not seem to clash with Moscow’s yet."

Moscow and Beijing are working out the experience of their strategic cooperation primarily when it comes to the economic convergence of the EAEU and the SREB. In June 2018, the two sides completed the Joint Feasible Studies on Completing the Eurasian Economic Partnership Agreement, which envisages liberalization of trade in services and investments, cooperation in the field of electronic commerce, in matters of competition, protection of intellectual property, etc. It is proposed to open the Agreement to all interested states. [xiv] On October 25, 2019, the Agreement on trade and economic cooperation between the EAEU and the PRC entered into force. Speaking at the plenary session of the 11th investment forum “Russia is Calling!” on November 20 of this year, President Vladimir Putin noted that Moscow and Beijing were working to establish a free trade zone (FTA).

As noted by the Russian Council on Foreign Affairs, this is not just about the integration of transport routes. “The goal is to link production and markets at every stage,” as well as creating an “institutional base” in combination with modernization of infrastructure and development of production “within its framework” [xv]. So, the planned construction of a high-speed fiber-optic communication line between Helsinki and Tokyo, which is being handled by the Russian PJSC Megafon and the Finnish Cinia Oy Company, would serve as an example of the digital integration of Europe and Asia. Megafon’s Strategy and Business Development Director Alexander Sobolev noted that “the Russian Arctic offers the shortest physically possible route between Northern Europe and Asia.” [xvi]

Russia is ready to expand ties with the European Union in other areas too. Indeed, President Putin came up with a long-term plan to create a Russia-EU free trade zone as early as in 2010. Russia continues to propose moving from competition between projects of "European and Eurasian integration" to their integration. To fully participate in Eurasian integration, the EU first needs to figure out the role it is going to play amid the current erosion of transatlantic relations. And secondly, how it intends to confront the growing threat of internal division. As for Russia, in spring 2019, it reiterated through its Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov its sustained interest in seeing the EU member-states join the Comprehensive Eurasian Partnership.

As we all know from history, the logic of developing mutually beneficial economic ties can help overcome the most deep-seated political and diplomatic contradictions. In the case of Eurasia, it looks like the processes of expanding trade and other economic relations are able to smooth over many geopolitical differences, and even completely resolve some of the existing political conflicts. At the same time, attempts to ignore Russia, or to minimize its role in continental integration, are extremely counterproductive.

The views of the author do not necessarily reflect the position of the Editorial Board.

[ii] https://inosmi.ru/economic/20190712/245450935.html

[iii] Also known as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

[iv] Following India’s exit from negotiation in autumn 2019.

[v] Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

[vi] https://expert.ru/2019/09/30/poyas/

[vii] https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/transkontinentalnye-transportnye-koridory-v-rossii

[ix] https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4142462

[x] https://inosmi.ru/economic/20190712/245450935.html

[xii] Nominal GDP, according to an October 2019 IMF assessment report.

[xiii] https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/05/01/chinas-ready-to-cash-in-on-a-melting-arctic/

[xiv] https://russiancouncil.ru/papers/Russia-Japan-WP50-Ru.pdf

[xvi] https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/24207

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:36 30.11.2019 •

10:36 30.11.2019 •