In the fall of 2019, Democratic Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, went on record saying that competition for resources was turning ecology into a national security issue. A growing number of politicians and experts share her opinion.

While most countries worldwide take a “mixed” picture of the consequences, upsides and downsides of global warming amid an ever-growing rivalry between states, the environmental idea is becoming a convenient and attractive tool to discredit opponents. Moreover, for some pro-Nature organizations, the proclaimed requisite to ensure environmental protection outweighs any objective needs for the development of both individual territories and entire states. Sometimes it becomes almost impossible to draw a line between sincere idealism and “lobbying for a new type of corporate interests.” As a result, criticism of a development model based on the use of hydrocarbons actually becomes an instrument of competition promoting the interests of the “green economy,” which in recent years has often proved to be less than ecologically impeccable. [i]

Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly reminded the international community of what the advocates of an immediate change to the global energy system fail to mention. Paradoxically, climate change and demands for a rash change of political priorities to combat it both threaten to increase inequality between countries.

On the one hand, political instability caused by the increasingly changing climate throws into question the long-term plans for the socio-economic development of entire regions and even continents. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), shortages of drinking water and large-scale human migration in search for a better live will emerge as the most pressing problems mankind will face in the near future. The regions where conflicts provoked by climate change will flare up in the coming years might include, among others, territories south of Russia’s borders and the Arctic.

On the other hand, less diversified economies, technological backwardness and outdated infrastructure put most economically underdeveloped and developing states at a disadvantage to the world’s most developed countries. The former argue, however, and with pretty good reason too, that many of the world’s most affluent countries keep using "dirty" technologies and production facilities in a bid to maintain their economic growth, including tax exemptions and even state subsidies. This is something ordinary citizens are well aware of, as is proved by the “green-oriented” political forces’ modest successes outside the "golden billion" states. In developed economies many people are wary of the high price of current “green” technologies, which promise not so obvious gains and only decades later at that,and politicians just can’t ignore this public sentiment. Finally, widespread forecasts of a global economic slowdown and even a possible recession are putting environmental problems on the back burner.

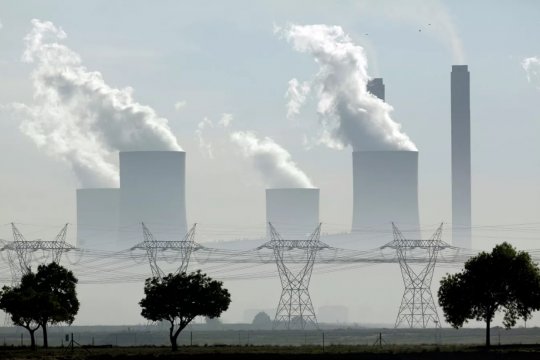

Besides, the much-trumpeted predictions of the imminent triumph of "green" technologies are not always grounded in reality. In February 2019, The Economist wrote that companies using traditional energy still generate more income compared to renewable energy projects. Global demand for oil continues to grow by an annual 1-2 percent, just like it has done the past 50 years. Most of the nature conservationists still move around in cars with internal combustion engines and fly on airplanes. Relying on some breakthrough developments and technologies whose prospects of mass-scale implementation remain dim would certainly be premature. The $300 billion that is currently being invested in renewable energy worldwide is just a drop in the ocean compared with investments in the development of fossil fuels. Finally, despite all high-profile statements regarding the introduction of electric vehicles, even in 2030, up to 85 percent of cars will still be running on the tried-and-true internal combustion engines.

In 2017, the US withdrew from the Paris climate agreement, and the Trump administration is now trying to breathe new life into the country’s coal industry. Even in many environmentally aware countries, broad sections of the public have not yet been convinced about the benefits of having to pay more for “green” goods and services. For example, the idea of stimulating economic growth by means of tax cuts is not popular with the high and mighty of the world’s leading economies. Meanwhile, experts consider monetary incentives, aimed at encouraging public support for technological and cultural changes aimed at reversing the global warming process as one of the most promising measures able to ease the skeptics’ fears. Therefore, assuring people that measures aimed at reducing harmful emissions will not cause a catastrophic blow to their personal well-being may prove a hard task.

In this regard, many politicians, administrators and experts are wondering just how dramatic changes in the existing economic structure over several decades will be able to reverse the negative climatic phenomena and how much should we focus on political, economic and social measures that would help individual countries and associations of states adapt to the objective trends of nature. And, finally, whether this is not just an attempt by the developed countries to hamper their current and potential rivals’ progress under the guise of solving environmental problems.

During 2019, the conflict between West and East European countries over the issue of unification of their environmental policy was heating up threating to further split the European Union. It turned out that “EU subsidies are no longer part of its policy, but rather a kind of gift for loyalty. We are talking about the familiar divide-and-rule policy” [ii], about an almost deliberate separation of EU states and regions, unwilling to unconditionally embrace decisions taken by the bloc’s leading countries and by Brussels. Simultaneously, the East European countries’ skepticism about the requirements of the earliest possible rejection of "dirty" technologies is fueled, among other things, by the example of Germany, where diversification of energy sources has effectively resulted in increased consumption of traditional fuels - coal and gas - with all the political and financial consequences this entails. This is due to the hasty closure of nuclear power plants that “green” generating units can’t fully compensate for.

In hindsight, one will have to admit that climate change has long influenced the fate of states and peoples. Some experts believe that the Late Antique Little Ice Age, “which began in the 5th century AD and lasted about a hundred years” [iii] could be a reason why the Byzantine Empire failed to maintain its growth. Today, access to fresh water is viewed as a leading factor that may spark conflicts both between countries and inside individual states. Since the mid-1990s, there have been forecasts that the 21st century wars will not be fought for oil, but for water. A population growth combined with an increase in the number of territories suffering from lack of water resources may lead to a significant increase in the number of refugees and internally displaced persons. This is a problem a number of regions of Africa and Eurasia, including Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan and Turkey, may soon be grappling with.

Catastrophic climate change is already contributing to an increase in cross-border migration, which is contributing to the rise of political extremism. Poor countries with growing populations are increasingly at risk of “political instability and violence.” The harmful effects of climate change can exacerbate economic turmoil in various parts of the globe. Meanwhile, population growth around the world may significantly outpace global economic growth, which, as many experts already predict, will result in a protracted period of stagnation at best. Overall, similar trends, which Republic.ru pointed to in 2019, give rise to political discourse about "the need to reconsider most of the existing paradigms," and, very likely, "away from classical capitalism and towards even greater state regulation."

Climate change, which provokes economic stagnation and intensifies cross-border and internal migration, can further embolden separatist movements in many parts of the world, including Europe. The fragmentation of countries into smaller territorial entities increases the risk of conflict, and sets the stage for outside intervention. Ultimately, the objective need for greater international cooperation in tackling global problems will face an equally objective upward trend in nationalism and isolationism.

For Russia, the Arctic offers a particularly important example of the geopolitical importance of the climate factor, as climate change is making this region increasingly accessible for economic development, while simultaneously making it vulnerable to new geopolitical challenges. Late this past summer, Bloomberg described the Arctic as “a region, whose growing importance is reshaping the world’s geo-economics.” As a result, the growing number of mineral exploration and development projects, as well as a projected increase in shipping volumes, will be ramping up competition, including military, between world powers.

There are other climate-related issues too. Russia also keeps reminding its foreign partners that, unlike the United States, it recently signed up to the Kyoto Protocol and, unlike the EU, has fully met its commitments under this accord. [iv] Inconsistencies in the assessment of the Russian forests’ and soil’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide are a matter of strategic importance. As the Expert magazine noted, Russian woodlands are an important factor in this country’s implementation from 2020 of the terms of the Paris Agreement under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, regulating measures to reduce carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere. The problem is that underestimation by foreign experts of the Russian forests’ CO2 absorption capacity can lead to the introduction by Western countries of a “carbon tax” on exported Russian gas.

Meanwhile, as President Putin noted during his traditional news conference summing up the results of the outgoing year 2019, Russia has “great advantages in the fight against climate change.” A “significant breakthrough” in the development of generating capacities in hydropower combined with vigorous development of gas production, including large-scale high-tech projects for LNG production, makes Russia the greenest in the world energy mix. [v] And Moscow does not intend to stop there. By ratifying the Paris Climate Agreement, Russia reaffirmed its strong commitment to international cooperation in the field of climate change, aimed at creating a paradigm of harmonious relations with nature. Working together, the international community needs to find a balance between a clean and safe environment while simultaneously maintaining the competitiveness of countries, peoples and regions, and the interests of their long-term sustainable development.

The views of the author do not necessarily reflect the position of the Editorial Board.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[i] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/anti.12261

[ii] https://inosmi.ru/politic/20190527/245149118.html

[iii] https://pogoda.mail.ru/news/36742482/

[iv] http://expert.ru/2011/07/22/a-skazhut-chto-eto-vse-rossiya/

[v] http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/58701

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:12 09.01.2020 •

12:12 09.01.2020 •