A paradox that largely goes unnoticed in Ukraine is that the country's own national literature is being sacrificed in the name of Ukrainian nationalism. In fact, Ukrainian literature fell victim to the political savagery of Ukrainian nationalists exactly when the same happened, in a wider-known campaign, to Russian literature in Ukraine: the country's radicals launched ideological wars on Russian and nominally their own classics as parallel offensives.

Upon scrutiny, the very concept of any sort of demarcation between Russian and Ukrainian literature appears to be at odds with reality. It is totally unclear, for example, to which of the two one should credit those of the poems of Ukraine's most acknowledged poet Taras Shevchenko which were composed in Russian, or the writings of Galician authors who used Iazychie, a language which blended the dialects of Bukovina, Galicia, and Ugric Rus' with Church Slavonic and was intended to serve as a bridge to literary Russian. Iazychie, it must be noted, was neither the Russian language proper, nor Ukrainian. The catalog of the Lviv National Scientific Library (West Ukraine) cites the works of a number of Galician authors in Iazychie or in Russian under the title of “Ukrainian Russian-language literature”.

Admitting that such works do belong to the realm of Ukrainian literature, Kyiv staunchly avoids integrating them into school and college curricula. Moreover, even literature teachers and professors in today's Ukraine have dubious reasons to claim being fully proficient in their subject – it would be much fairer to say that they are familiar with about half of it.

The body of Ukrainian literature as it is interpreted today in Ukraine is indeed only one half of what it used to be. The amputation began back in the Soviet era, when any references to the existence of the triune Russian nation comprising Russians, Ukrainians, and Belorussians were removed ruthlessly from Ukrainian writings. The process had gone further over the years of Ukraine's independence, leaving the literature as a whole defaced, crippled and de-energized. For decades, Russophobia seems to have been the main criterion for adding a particular author to the list of contributors to Ukrainian literature. As a result, the literature, already forced to stay out of touch with a great deal of its legacy, is increasingly saturated with nationalist venom and degenerates into crude propaganda.

The Kyiv administration invests heavily in the transformation, churning out plans and initiatives supposed to cast a long shadow over all things Russian, to highlight, in comparison, the loftiness of the Ukrainian cause, and, above all, to assert the absolute incompatibility of Ukrainian and Russian cultures which are portrayed as if they hail from distant galaxies.

Even the Security Service of Ukraine, which one might expect to be charged with a mission of different character, chose to intervene on the cultural front: the site of the agency features a section titled “200 Years of the Non-canonical Shevchenko” (1). From the perspective of the Kyiv administration, “non-canonical” predictably translates as Russophobic. The approach - reducing Shevchenko's uniqueness to blunt nationalism – is shallow and short-sighted, and though the poet was by no means a Russophile, he was anything but an ardent Russophobe. Rather, Shevchenko's position on the issues evolved as circumstances changed.

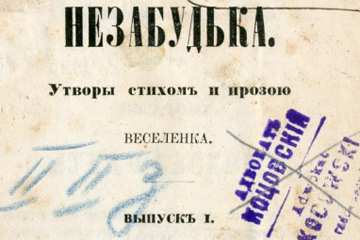

For Kyiv, even the slightest Russophile leanings are a reason to drop an author from the cohort of Ukrainian classic writers. An inexperienced reader is tempted to conclude that serious Ukrainian literature as such is limited to a collection of nationally oriented texts by nationally oriented writers, but the perception is completely wrong. For example, chances are slim that verse from the “Forget-Me-Not” volume, published in Lviv in 1873 (2), will ever surface in any of Ukraine's study programs. Its opening poem with a tragic name “Sentence” reads: “Russian flowers I nurture in my home town, caring not for those who are not happy that there they are” and does not fit with the ideology dominant in the country, despite being written in one of its native dialects. Another poem from the volume - “All for Russia” - repeatedly mentions “the Russian spirit, young as ever” and similarly will not be allowed by Ukrainian education officials to reach the readership. The truth is that the above is a recurrent theme common to quite a few Ukrainian authors, but their works are systemically filtered out by censorship and denied recognition as ideology dominates the scene.

Poem “The Thought” starts with “Dear friend, are you aware of how joyful life is where the Russian mountains overlook the waters of the Stryi”, the latter being a river in the Lviv province. The Russian mountains in the case, apparently must be the Carpathian Mountains. These days, the area is kept in a tight grip by Ukrainian radicals, but the poem dates back to the late XIX century, an epoch when many in the Carpathian region were keen on their connection to Russia. It is deeply abnormal that Ukrainian nationalists who are, in the historical sense, newcomers in the region revise and redefine its legacy.

The main allegation leveled at Russia and Russian culture by radicals from the ranks of the Ukrainian intelligentsia is that Ukraine's original legacy used to be suppressed, particularly in the form of denying the due acclaim to the works by Ukrainian authors. In reality, it is the current Ukrainian administration who imposes crude censorship on Ukrainian literature, ejecting significant parts of it from school and college curricula, shelving serious books in dusty archives, and responding with absurd accusations of humanitarian subversion to any attempts to acquaint the audience with a bigger cultural picture.

The time has come to publish alternative versions of Ukrainian literature textbooks which should incorporate the very works which the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science is trying to conceal. Keeping them out of the spotlight, advancing biased interpretations of Ukrainian legacy, and pursuing a surgical approach to it is a policy which works for the official Kyiv but runs contrary to the interests of the Ukrainian people who, as a result, are not allowed to fully know their own literature.

1) http://www.sbu.gov.ua/sbu/control/uk/index

2) “Forget-Me-Not”, verse and prose. Lviv, 1873

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

2:07 04.07.2014 •

2:07 04.07.2014 •