Being the emblem and the epicenter of Ukrainian nationalism seems to be Galicia's traditional posture in more or less every epoch. Seen as such by Ukrainian nationalists and their opponents alike, Galicia had to suffice with a peripheral role throughout the times of the Russian Empire or of the Soviet Union. The province moved into the spotlight every time Ukraine equipped itself with sovereign statehood, but receded to the background whenever Ukraine merged into neighboring geopolitical giants. The rough guess at the nature of the fluctuating status of Galicia would be that, as a tiny province, it could enjoy appreciable influence only within a country of modest proportions, but, the above being essentially correct, culture factored into the situation at least as much as geography. For long periods of its history, Galicia used to belong to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and to the Austro-Hungarian Empire while remaining, in the cultural sense and in a broader historical perspective, a part of the Russian world. Galicia's particular cultural contribution dissolved in the civilizational mixes of empires and retained measurable concentrations only on the regional level – within Galicia proper, along with the provinces like Volhynia and Bukovina – but, overall, was inversely proportional to the sizes of the countries into which it was incorporated.

The fairly recent dynamics fully exemplifies the trend. Galicia's zone of cultural and political prominence was limited to the western flank of Ukraine in the Soviet era, when Ukraine itself was built into the USSR. The province gained in importance visibly the moment the former Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic re-branded itself as independent Ukraine - and still, Galicia would have never been able to shape the ideology of independent Ukraine to the current extent were it not for the the official Kyiv's material and administrative support for Galician nationalism.

Historically, the debate on the geopolitical potential of Galicia is traced back to S. Tomashevsky and I. Krevetsky. The former, along with V. Lypynsky, is also credited with formulating the doctrine of Ukrainian “territorialism”, which postulates that for anyone in Ukraine, sharing the territory should be the key unifying factor automatically trumping all others. In Lypynsky's view, an independence-minded Ukrainian has more in common with a fellow-Ukrainian who is a Polonophile or Russophile than with any different national, albeit with congenial political beliefs. The motivation behind the theory, therefore, is to somehow create a nation based on territory and regardless of the ethnicity of the population inhabiting it.

Lypynsky and Tomashevsky, it must be noted, were largely assimilated ethnic Poles from westrern Ukraine. In contrast to Lypynsky, Tomashevsky held anti-Russian views and thought of Ukraine as a geographic entirety, attaching no importance to its patchy ethnic composition and focusing staunchly on his original concept of the “Ukrainian soil”. Tomashevsky ascribed to western Ukraine the spiritual leadership in what concerned Ukraine's presumed drive towards independent statehood and derived the corresponding legacy from the Principality of Galicia–Volhynia, overlooking, on political grounds, its historical continuity with Kievan Rus'. Tomashevsky lauded the West Ukrainian spiritual human type which he described as a combination of Byzantine form and Roman content and, further, as a carrier of serious ecumenist potential. Tomashevsky's perceived Galicia was a stronghold and the cultural nucleus of the Ukrainian nation casting its religious and cultural influences over a significant portion of Eurasia up to the ethnic and cultural frontier of Russia which, in Tomashevsky's mind, was by definition a power hostile to the Ukrainian cause. Tomashevsky stressed that Galicia was located at the very heart of Europe, with Peremyshl approximately equidistant from France's Brest at the Atlantic coast and Astrakhan at the Caspian Sea, from Vienna and Kyiv, from Pustozyorsk at the Arctic Ocean and Gibraltar, from St. Petersburg and Rome, from Stockholm and Thessaloniki, from Copenhagen or Sund – and Constantinople and the Bosporus [1].

Krevetsky's ideas were largely consonant with those expressed by his contemporary Tomashevsky. Krevetsky was convinced that Galicia had a unique geopolitical talent to grant primacy in European affairs to the power which managed to add the province to the list of its possessions. To illustrate the notion, he cited the recurrent XVIII-XIX century strife between Austria and Russia over the Carpathian region, including Galicia. Krevetsky, it appears, felt that Central Europe's history nothing less than revolved around the conflict of key powers over Galicia which, therefore, was a civilizational focal point permanently communicating its vibes to the whole realm of European politics rather than a province of marginal importance to it.

In other words, Tomashevsky and Krevetsky portrayed Galicia as a unique cultural and political actor with manifest geopolitical destiny. Both vehemently rejected the notion that the province could be in any sense peripheral and saw it as the scene of definitive European dramas.

There seems to be an element of truth in the claims concerning the strategic significance of Galicia if you look specifically at the periods of time when the conflict between Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire peaked, but, in general, it is an inescapable conclusion that both Tomashevsky and Krevetsky ultimately switched from practically oriented geopolitics to some sort of metaphysics in dealing with the subject. B. Shaw wrote that “a healthy nation is as unconscious of its nationality as a healthy man of his bones”, and a reasonable variation of the same wisdom implies that being preoccupied with disproving one's marginal status is indicative of actually living with it.

As for Galicia, it has to be admitted that, for the most part, the province used to be of marginal importance to big-league politics, only fleetingly – and only within a limited strategic scope - taking a bigger role in the game played by such heavyweights as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Russia. Invariably, Galicia ended up drifting back into relative obscurity and staying in that condition for ages. Mastering Galicia did not prevent Poland from subsequent partitions or the Austro-Hungarian Empire from falling apart. At the moment, Galicia is in Ukraine, but the country faces a major instability and still crumbles. Moreover, the ardently nationalist Galicia's tendency to communicate anti-Russian vibes to the surroundings, especially in the direction of the Russian frontier, is the root cause of the crisis which is sure to have irreversible consequences for the immature Ukrainian statehood.

Galicia being notoriously conservative, the flavor explainably permeates the writings of its conservatives Tomashevsky and Krevetsky. It has to be taken into account in the context that Galicean conservatism narrowly cites the Austrian legacy which has no appeal whatsoever across the rest of Ukraine. It is fair to say that Galicia, which cherishes its Austrian heritage from the Habsburg era and is chronically wary of any alternatives to this cultural and ideological framework, remains a mostly isolated phenomenon in Ukraine.

Dictating ideological trends, which is the mission Ukrainian nationalist authors entrust Galicia with, would clearly take a lot more than the province can accomplish. For that, the province would have to prove being capable of projecting its influence on the nationwide scale, which cannot happen due to profound reasons. Ukraine beyond Galicia takes no interest in the Habsburg legacy, and the citizens of the country, far from being inspired by Galician invectives, simply face Kyiv's uninvited policy of promoting and aggressively enforcing Galicean concepts of Ukrainian history.

Altogether, Galicia fails to cope with the geographic dimensions of Ukraine. Pretending to be an anti-imperial stronghold, the province de facto invented by the Habsburg empire blew the task which empires normally tackle on the go, namely, that of spreading their political, cultural, and ideological influences far beyond the original ethnic confines. The writings of Galicean nationalist authors represent an attempt to squeeze the real history of the region into a one-dimensional, deliberately anti-Russian scheme. Tomashevsky and Krevetsky, for example, opposed Galicia's pro-Russian movement which, by all means, was a legitimate component of the history of the province on pars with its pro-Ukrainian counterparts.

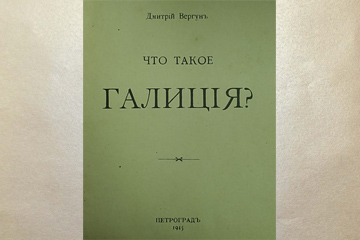

Prominent writer and Pan-Slavist Dmytro Werhun (1871–1951) offered a much more nuanced picture of the Galicean history. A contemporary of Tomashevsky (1875-1930) and Krevetsky (1883-1940), Werhun stressed in his “What is Galicia?” [2] the connection between Galicia and the wider Rus', and looked boldly beyond the temporal and geographic bounds of the Principality of Galicia–Volhynia. Drawing an explanation of Galicia's character from the history of Galicia–Volhynia, Tomashevsky grossly overstated the Galicean historical singularity and ignored the bonds which existed naturally between Galicia and the Russian world. He also overlooked the negative impact the latter suffered as a whole when the bonds had been severed militarily and politically by Western powers.

The myth of Galicia's centrality to European history is not going to collapse, considering that serious political forces exploit it to their own ends and will keep reinflating it. In contrast, the Ukrainian statehood which has been supposed to be energized by the Galicean myth throughout the past 23 years is collapsing, and this is a process we are witnessing at the moment.

- Oleg Bagan, “Geopolitical and Civilizational Role of Galicia in the Early XX Century Genesis of Ukraine”. D. Dontsov Research and Ideology Center.

- Dmytro Werhun, “What is Galicia?” . St. Petersburg, 1914

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

22:12 04.08.2014 •

22:12 04.08.2014 •