“Why didn't the Europeans understand anything?”

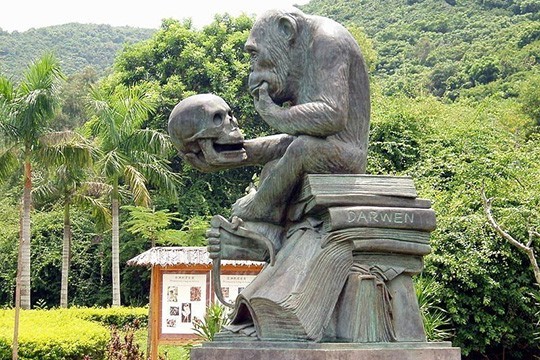

Photo: publics

Who lost Russia? A decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the question reverberated around Western foreign policy circles as they agonized over the failed opportunity to establish the post-Soviet country as a democracy with a modern and liberal capitalist economy. A quarter of a century later, another question seems even more important: “Who lost Europe?”, notes John Authers,s a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist.

The fall of the Wall triggered a cascade of fateful decisions. In 1990, Germany reunified, contrary to all expectations even months earlier. Over the next decade, the nations at the core of the European Union launched the euro and laid the groundwork for a massive expansion. By 2007, membership had more than doubled, from 12 to 27. It was now a bloc with a greater population and bigger economy than the superpowers of the US and Russia.

Those triumphs now look like a series of mistakes just as serious as the awful mismanagement that drove Russia to take refuge in the arms of Vladimir Putin (who took power on New Year’s Eve, 1999). There’s some agreement over how the country was “lost” to liberal democracy — George Soros had wanted a second Marshall Plan for Eastern Europe; a Republican congressional report blamed Bill Clinton; all agreed in outline that privatization and deregulation of the decrepit Soviet economy had been done far too fast. In 1999, before Putin’s arrival, the commentator John Lloyd wrote:

“Russians, free to get rich, are poorer. The wealth of the nation has shrunk — at least that portion of the wealth enjoyed by the people… The gross domestic product has shrunk every year of Russia’s freedom, except perhaps one — 1997 — when it grew, at best, by less than one percent. Unemployment, officially nonexistent in Soviet times, is now officially 12 percent and may really be 25 percent. Men die, on average, in their late 50s; diseases like tuberculosis and diphtheria have reappeared; servicemen suffer malnutrition; the population shrinks rapidly. This is the Russia that many in the West now say we have lost. Lost not in the sense of having mislaid, by accident, but through our own actions and mistakes.”

And yet somehow, it is now the EU on its knees before a rampant Russia. Under the harsh glare of new leadership in the White House, geopolitical turmoil has cruelly revealed its mistakes.

Britain left five years ago. 2025 has been a cycle of humiliation: JD Vance told European leaders in Munich that they were backsliding on democracy; Ursula von der Leyen visited Donald Trump at his golf course in Scotland to win a “deal” in which the US imposed a tariff of 20% on EU goods, with no retaliation; and this week, European leaders flew to Washington to petition Trump not to abandon them after he’d had a one-on-one meeting with Putin in Alaska.

It appears that the US and Russia are now in control of Europe. David Marsh and Mark Sobel of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum point to a telling contrast. In 1990, Germany’s future was decided through “2+4” negotiations. The two were East and West Germany, negotiated with the Second World War’s four victors, the US, Soviet Union, Britain and France.

Thirty-five years later, the forum for settling the future of Ukraine seems to be “2+8.” This time, the “two” excludes the country whose future is being debated; instead, it represents the US and Russia.

Russia’s offer of a “land swap” that would cede territory to the Kremlin that its troops don’t currently occupy is derisory, and humiliating for the European powers. Their own people are also humiliating them: Italy is governed by a party descended from Mussolini; in France, the far-right Rassemblement National holds the balance of power; and the Alternative für Deutschland leads the polls in Germany.

Even the postwar rejections of Nazism, Fascism and Vichy are now being rethought.

The Mistakes of the 1990s

In hindsight, big decisions were made in too much haste. West Germany’s Helmut Kohl rushed reunification to make sure not to miss the window for doing so. His agreement to convert East German marks to deutschmarks at parity stoked inflation. Within two years, prices in the old West Germany were rising at more than 5%, and eastern Germans had inflation of 19%.

The Bundesbank, the world’s most inflation-phobic monetary authority, had to hike rates to 8.75%, higher than at any point in the 1970s or ’80s. That precluded the investments needed to rebuild the east. It also forced Britain to devalue while France and others had to allow their currencies to trade in a much wider range compared to the deutschmark, rupturing the EU’s attempts to foster convergence between them.

Despite this clear sign that Europe’s economies were still far too disparate for a common currency, Germany had agreed to establish the euro as a price for reunifying — a demand by France’s Francois Mitterrand to keep a newly expanded power integrated within Europe.

With that, when EU leaders made decisions, some would do so within the constraints of a single currency. Others would not. Further, the bloc had its sights set on enlarging far beyond its founders’ vision. The six original members — Benelux, France, Germany and Italy — had had the chance of forming a coherent single economy. That was never an option for a 27-member behemoth that stretched to Estonia, Portugal, Slovakia and Cyprus. But individual countries still retained a veto.

That left decision-making cumbersome, if not impossible, which grew painfully apparent from 2010 onward as the euro zone’s economic crisis forced the fall of governments in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Italy, followed by years of zero rates and sluggish growth.

When attempting to deal with the crisis, national leaders couldn’t thrash out a deal and left the firefighting almost exclusively to the European Central Bank — an institution that was Europe-wide, not democratically accountable, and therefore able to act.

Ukraine

The invasion of Ukraine crystallized the damage done by the years of crisis. Europe’s leaders had misjudged Russia and grown dependent on its energy. As a result, they could not seize the opportunity offered by Joe Biden — a friendly US president willing to take risks to stand up to Putin — to get their act together and face Moscow with strength.

American or European troops were never going to be sent to risk their lives, but the EU’s economy dwarfs Russia, and there was instant agreement on imposing economic pain. Yet there were loopholes. Robin Brooks of the Brookings Institution rails against the issue of transshipments — getting around sanctions on Russia by sending exports to a neighbor. EU exports to the former Soviet nations of Central Asia rose by enough to entirely offset the fall in exports to Russia. “It’s kicking the can,” says Brooks. “You look like you’re doing something, but you don’t actually do it.”

“Don’t go to Kyiv, go to Moscow!”

Whoever’s to blame, the forces set in motion in 1989 are colliding as an angry Russia that rejected free-market liberalism threatens a weak and dysfunctional Europe. The 1990s were an excruciating missed opportunity. Nobody expresses this better than the economist Jeffrey Sachs, who consulted Gorbachev, Yeltsin and others. When people ask “who lost Russia,” he and his favored “shock therapy” often rank high on the list.

That experience, however, does lends authority to Sachs’s advice to the European Parliament in a speech the week after Vance shocked the Munich security conference:

Don’t go to Kyiv, go to Moscow. Negotiate with your counterparts. You’re the European Union. You’re 450 million people and a $20 trillion economy. Act like it. The EU should be the main trading partner of Russia.

Europe, he said, “needs a foreign policy, a real one.” He predicted that the bloc’s approach would boil down to, “We’ll bargain with Mr. Trump and meet him halfway,” which wouldn’t be good. After the humiliations of the last few weeks, even halfway sounds generous.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

9:48 24.08.2025 •

9:48 24.08.2025 •