Pic.: publics

Nothing lasts forever: Every international order finds its end. Pax Romana stabilized the greater Mediterranean world, until decline set in. The British global order flourished in the 19th century but came apart amid two world wars in the 20th.

Today, in an unruly world led by an erratic America, it’s hard not to wonder if the US-led order is on its way out, Bloomberg writes.

China, Russia, Iran, North Korea are challenging a system they view as dangerous to their illiberal regimes and oppressive to their geopolitical ambitions. The Global South has become disillusioned with Western dominance. The US itself has seemed ambivalent, in recent decades, about world leadership. Threats to its economic and military supremacy have grown more severe.

Visit nearly any US ally, and you’ll notice conviction that American power remains necessary — and concern that the post-World War II order is slipping away. So how real is the danger? Let’s consider the three ways an order can come apart.

Losing a War

One path to failure runs through defeat or devastation in war. Nothing ruptures the authority of a hegemonic power like a humiliating beatdown on the battlefield. The Athenian empire collapsed after losing the Great Peloponnesian War. Britain won World War I, but never recovered from its costs.

For decades, America has been the sole superpower. As last month’s attack on Iran’s nuclear program reminded us, the Pentagon still possesses power-projection capabilities without peer. But anyone who thinks the US is militarily invincible hasn’t been paying attention.

The Pentagon faces a vexing military arithmetic problem. Several challenges — from Russia in Europe, Iran and its proxies in the Middle East, and China and North Korea in Asia — are stretching US resources. A superpower with a military designed to fight one war at a time is always at risk in a world of multiple, interlocking threats. But the danger of crushing defeat is most concentrated in the Western Pacific. The Chinese threat is real, “and it could be imminent,” Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth observed this year.

A US-China war would cause cascading economic carnage and bring serious risks of nuclear escalation. And if America lost — which is a real possibility — the damage to the US order would be profound. America’s alliances in the Indo-Pacific might fracture. A broken US military might struggle to police other parts of the world.

American military spending is below 3.5% of GDP, among the lowest levels since World War II, and could dip next year. Stockpiles of munitions and missile defenses are, reportedly, low, and have been depleted by recent scrapes in the Middle East.

With a moribund shipbuilding industry and a sluggish, fragile industrial base, America would struggle to replace assets lost in the opening phase of a fight. “You can’t AI your way out of material deficiency,” Paparo has argued: A country that can’t replace battlefield losses won’t win a grinding, great-power war.

An Economic Collapse

Orders don’t have to explode violently. They can also implode, when the leading power can’t — or won’t — sustain the economic arrangements that make the system work. The British order crumbled when two world wars bankrupted the empire. The American order has long rested on two economic pillars.

The first is simply the economic and financial wherewithal to sustain America’s global power — among other things, to pay for military capabilities that keep revisionist threats in check. The second pillar consists of economic arrangements that reinforce strategic commitments: the international economic leadership, the ties of trade and investment, that bind Washington to its allies and give them all a shared stake in preserving a US-led world.

Both pillars have been remarkably durable. For all the talk of decline, America’s share of global GDP is roughly the same as it was in the 1970s. The dollar dominates world trade and finance. Foreign investors have long been willing to support dollar dominance, and finance large US deficits, because those arrangements help Washington fund its alliance commitments and military muscle.

Three Real Challenges to the Order’s Economic Structure

There are, however, three real challenges to the order’s economic structure: Profligacy, protectionism and politicization. All are getting worse.

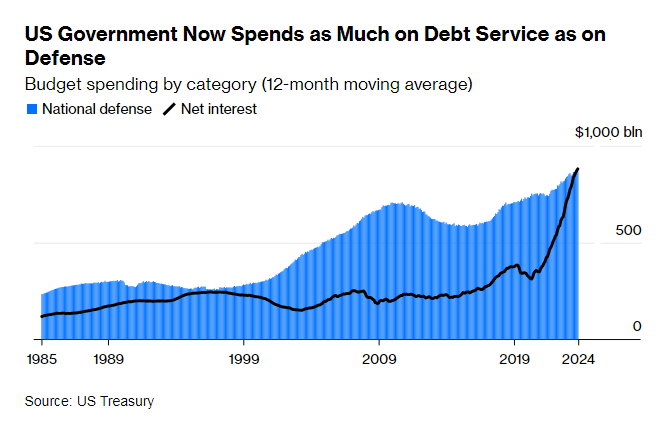

First, profligacy. A quarter-century ago, the US had a budget surplus. Now, it’s deficits without end. Publicly held US debt is around 100% of GDP. It will soon eclipse the 119% America reached at the close of World War II. And if the spending and taxation levels enshrined in Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill become permanent, debt could exceed 200% of GDP by 2050.

As debt and deficits grow, interest payments will increase and borrowing costs could rise, crimping growth and crowding out spending on defense. At some point, continued profligacy could undermine dollar hegemony, weakening America’s global power — its ability to wield sanctions, for instance — and compounding all its other economic problems.

There’s no reliable formula for determining where, exactly, that dangerous threshold lies — where persistent fiscal recklessness finally makes global leadership unaffordable or otherwise exacts a crushing geopolitical price. But the US seems intent on finding out.

Second, protectionism. The US has never been shy about renegotiating economic relationships with partners: Recall the brutal trade fights with Japan in the 1980s. But Trump’s extreme affinity for tariffs could have more lasting, corrosive effects.

US allies complain that those tariffs are making it harder to raise defense spending. The more the US brawls over trade with allies, the more it undermines the collective cohesion and resilience needed to outcompete a mercantilist China on everything from shipbuilding to AI.

Third, politicization. Trump’s campaign against the independence of the Federal Reserve threatens to undermine the apolitical, competent management of the US economy and weaken the Fed’s ability to act as global stabilizer in times of crisis. Trump’s willy-nilly use of tariffs in political disputes — over migration, drugs, or the legal woes of his illiberal fellow travelers — is making America a force for geo-economic upheaval.

Trump is playing fast and loose with the global economy. It’s hard to see many countries supporting that sort of superpower over time.

The End of the World as We Know It

President Bill Clinton used to say that a lot of people have lost money by betting against America. The same goes for the American order. In the early 1960s, no less a figure than Henry Kissinger argued that America and the system it had created were careening toward disaster. In the decades since, the end of the US order has often been predicted and consistently failed to occur.

The fact that the order has survived for generations reflects its great resilience, and the great exertions America and its allies have made to defend it when it is threatened. But don’t think that a good thing must go on forever, or that the US is immune from the dangers that brought old orders down.

That order could meet its end in a sharp, bloody clash in the Western Pacific. Or in a long crisis caused by accumulating profligacy and protectionism. Or in the sad slide into irrelevance that results from persistent erosion of rules. Or, perhaps, the demise of the American order will occur, someday, at the intersection of these three dangerous paths.

History tells us that there are many ways in which orders unravel. A worrying marker of our current moment is that America is courting all of them at once.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:59 04.08.2025 •

11:59 04.08.2025 •