Pic.: businesspost.ng

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes — take Saudi Arabia pushing OPEC to boost production, seemingly to humble cartel cheaters, writes Javier Blas, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities.

If it sounds familiar, it’s just coincidence. I’m not talking about last week, but rather 1997, when an OPEC meeting in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta hiked output just as the Asian financial crisis was gaining momentum (and the week Indonesia’s rupiah cratered). Few anticipated how ugly the combination of extra production and slowing economies would be. A year later, oil prices had plunged below $10 a barrel, and the policy mistake lives forever in OPEC’s memory as the “Ghost of Jakarta.”

Today, we are only sowing the seeds of a global economic disruption. But there are many parallels, including the fact that the oil market was weaker than many wanted to believe. If history is any guide, we are far from the oil market’s bottom.

The situation is fluid and much depends on the next steps taken by the White House and the OPEC+ alliance. Still, we can draw a few tentative conclusions.

1) So far, both the White House and, crucially, Saudi Arabia appear to be happy with a more than 10% plunge in crude prices since Donald Trump announced the tariffs. So don’t bet either will step in. Trump needs lower oil prices to offset the inflationary impact of the trade war. And make no mistake, the will and intent of the Saudis last week was to push oil prices lower. Period. That’s why they scheduled an impromptu meeting to announce the production hike hours before Trump launched his trade war, knowing it would maximize the bearish message.

2) It would be a mistake to read 2025 throughout the very same lens of the last oil price war, fought in 2020 between Saudi Arabia and Russia. That price war, combined with the Covid-19 pandemic, sent oil prices below zero. For now, Riyadh isn’t replicating the same bullying tactics it deployed then. If in 2020 the kingdom launched the oil equivalent of a nuclear first strike, this time the military analogy would look more like a commando raid.

3) Oil demand forecasts are way too high at an annual growth of more than 1 million barrels a day for 2025. My guess is that they will be cut by between a third and a half. History is a guide: In 1998, after the outbreak of the Asian crisis, oil demand grew by just 400,000 barrels a day, less than half the pre-crisis run rate. The crisis affected several fast-growing economies that are today the very same targeted with the highest tariffs (think Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, China). Those nations are important because they are the engine of global oil demand growth, so an economic slowdown there has an outsize impact on petroleum demand.

4) With Saudi Arabia pumping more and global consumption growth weakening, supply-and-demand will need to rebalance the hard way via a slowdown in non-OPEC+ output growth. But that’s a process measured in quarters, rather than weeks or months.

Most of the rebalancing will fall on US shale companies. It’s been less than a week since the crash started, but my industry soundings indicate that not only are most shale companies already planning spending cuts, but a handful were warned over the weekend by their lenders that they need to reduce drilling immediately to avoid breaching loan covenants.

5) Finally, don’t forget psychology. The institutional memory of oil trading desks is firmly anchored in two oil price wars that brought ultra-low prices: The one the Saudis launched in late 2014 against the US shale industry, and the one in 2020 pitting the Saudis against the Russians. The first saw WTI dropping to less than $30 a barrel; the second saw it plunging to an all-time low of minus $40 a barrel. Unsurprisingly, everyone is today trying to hedge downside risk via put options, whose trading volume has exploded. With that historical background in mind, I don’t think many will try to catch a falling knife.

The market rout sparked by President Donald Trump’s trade war is touching almost every part of the economy. But there are probably few industries feeling more aggrieved right now than US shale oil, Bloomberg notes. Over the last 15 years, it has made America the world’s top crude producer, lowered energy costs and fueled a boom in petrochemicals and natural gas exports. It also contributed heavily to Trump’s election campaign.

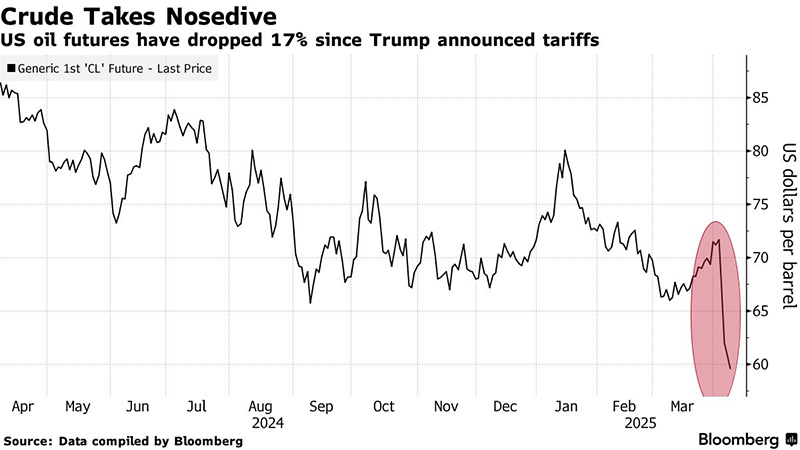

And yet half of the 20 worst-performing stocks on the S&P 500 Index since Trump announced his tariffs April 2 are in the oil, gas and petrochemical sector, while crude prices have plunged to the lowest in four years.

The growing unease reflects how Trump’s effort to re-write global trade rules is undermining his goal to supercharge US fossil-fuel production and achieve “energy dominance.” Executives are loathing to boost US oil supply with West Texas Intermediate down about 23% since Trump’s inauguration less than three months ago. It’s now hovering under $60 a barrel, below the level they say they need for new wells to break even, according to a survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Adding to their woes, OPEC and its allies last week pledged to triple a production increase previously scheduled for May. The cartel announced it hours after Trump unveiled his tariffs.

“Those two things together shocked the whole industry,” said Linhua Guan, CEO of Houston-based oil producer Surge Energy.

US crude futures fell for a fourth-consecutive trading session Tuesday, dropping to $59.58. It was the first time WTI closed below $60 a barrel since 2021.

If prices fall to $50 a barrel, production in the Lower 48 states could drop by more than 1 million barrels a day over the next 12 months, according to S&P Global Commodity Insights. That’s about 7% of the current US total.

Even if prices bounce back to $65, shale operators probably would shut down 25 drilling rigs and hold US oil production flat, Citigroup Inc. analysts warned last month.

The drop would be particularly damaging because output from shale wells declines much faster than conventional wells in the Gulf of Mexico or elsewhere, falling 60% or more during the first year they come online.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:09 11.04.2025 •

11:09 11.04.2025 •