For a time after the cold war the world seemed to move towards an international rules-based order with less conflict, more democracy and open trade. Lawyers looked forward to “universal jurisdiction” — a borderless fight against impunity. But the order, always imperfect, is breaking up because of intensifying geopolitical rivalries — and efforts to uphold it may only expose its weaknesses, notes ‘The Economist’.

America, the chief architect of the system, undermined it with the excesses of its “war on terror”, not least after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Now critics accuse it of being complicit in atrocities by supporting Israel’s war on terror. Israeli forces have killed tens of thousands of Palestinians in an attempt to destroy Hamas, which killed or kidnapped some 1,400 Israelis on October 7th.

China and Russia mock the “rules-based international order”, a phrase intoned by President Joe Biden, as a cloak for American dominance. The fuzzy term is similar in meaning to “liberal international order” (a more common phrase that can confuse Americans, for whom “liberal” means left-wing. Antony Blinken, his secretary of state, says it is the broad system “of laws, agreements, principles and institutions” to manage relations between states, prevent conflict and uphold human rights. Critics reckon America avoids referring to “international law” so as to preserve its freedom to use force.

International law has long recognized states’ sovereign immunity, which protects them from legal action in foreign courts. But their use of violence at home or abroad is circumscribed. The un Charter of 1945 forbids the use of force in international disputes except in self-defence. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 enshrines individual rights to life, liberty and the security of the person. The Geneva Conventions of 1949 regulate war and protect non-combatants. Further conventions ban genocide, torture and more.

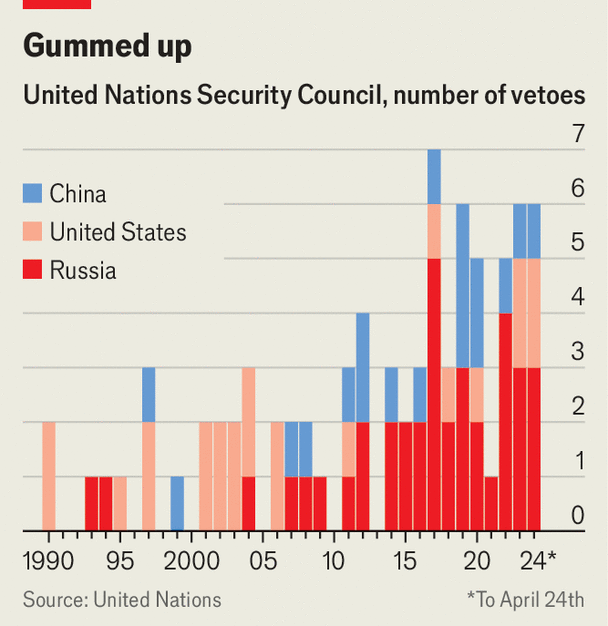

International courts punish breaches. But there is no global policeman to enforce their rulings. Worse, the UN Security Council, the pinnacle of the system — which can authorize force to maintain peace and security — is all but paralyzed by the power of veto held by its five permanent members (see chart).

America increasingly aims to preserve the liberal order through military alliances in Europe and Asia. It regards the g7 as the “steering committee” of the world’s advanced democracies. Some foresee a dual order: a liberal one dominated by America and an illiberal one centred on China.

Even so, human-rights lawyers are trying to preserve the idea of universal rules, and are working through international courts given the UN’s impotence. The system has many gaps, in jurisdiction and enforcement. It is “a broken-down car that somehow keeps moving”, says Harold Koh of Yale University.

The International Criminal Court (ICC), more like a criminal court, investigates people rather than states. But it can prosecute a broader range of offences — not only genocide but also crimes against humanity and war crimes. Independent prosecutors decide whether to issue arrest warrants, but rely on states to enact them. The ICC can investigate a fourth crime, of “aggression” — regarded as the “supreme international crime” that leads to other atrocities — but only if suspects are citizens of state parties. The ICC’s work is thus limited because dozens of countries have declined to join the court — among them America, Russia, China, India and Israel.

Confronted with an “epidemic of inhumanity” the ICC chief prosecutor Karim Khan has argued, the world must “cling to the law” more tightly. The unspoken danger is that, should he and others fail to curb the horrors, the law will collapse and there will be little left to hold onto.

The British magazine is literally crying because the world dominance of the Anglo-Saxons is disappearing before our eyes…

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:08 15.05.2024 •

12:08 15.05.2024 •