Pic.: ‘The Spectator’

Last month, after 21 years studying and teaching Classics at the University of Cambridge, I resigned. I loved my job. And it’s precisely because I loved the job I was paid to do, and because I believe so firmly in preserving the excellence of higher education, in Britain and beyond, that I have left, professor David Butterfield writes at ‘The Spectator’.

When I arrived in Cambridge two decades ago, giants were still walking the earth. Students could attend any lecture, at any level, in any department; graduate and research seminars were open to any interested party, and you could sit at the feet of the greats. Unforgettable gatherings of everyone from undergraduates to professors would discuss the big questions late into the night.

Cambridge became one of the best universities in the world. This is why its contribution to the arts and sciences outstrips any other institute of higher education.

A few years ago, Cambridge’s class lists became private. University administrators alleged grounds of ‘data protection’, after a minority of students campaigned under the banner of ‘our grade, our choice’. What was first an opt-out for students soon became uniform policy. No longer can undergraduates discover who did best (or worst) in their cohort, their subject, their college – even academics are given limited access to results, based upon their role. The desire to save students personal embarrassment has thus snuffed out much of the competitive spirit of the university. (The unofficial ranking of overall college performances, the Tompkins table, still circulates quietly, but only because a senior tutor leaks the data.)

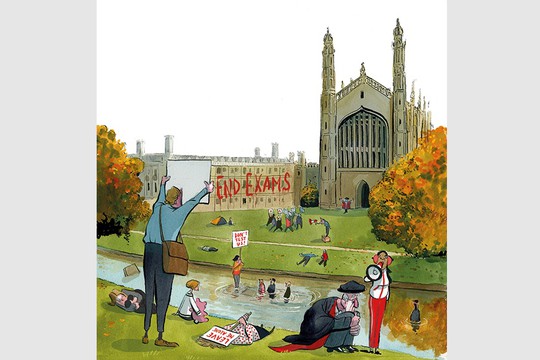

Now even the fate of examinations hangs in the balance. There is a strong push, from students, administrators and a clutch of academics, to reduce or remove the traditional closed-book exam, which tested knowledge, ingenuity and (where appropriate) rhetoric under the real pressures of time and circumstance. Not only have many exams become open-book exercises to be carried out from students’ rooms, but there has been a marked increase in coursework. Naturally this is less stressful for students, but few see the irony of having their final academic grade being based upon earlier, i.e. less learned, versions of themselves. Meanwhile, the university has no clue whatsoever about how to deal with the rampant use of illegitimate, but increasingly undetectable, AI software.

For various reasons declarations of disability have spiked dramatically. Over the past 15 years, disability at Cambridge has increased more than fivefold, and is now declared by some 6,000 students (roughly one in four). The two major areas of growth have been ‘mental health conditions’ and ‘specific learning difficulties’. Many students register anxiety as the cause.

Whatever the truth behind the much-discussed ‘mental health crisis’, it has ushered in developments that disrupt university life. Many students are now excused from writing essays and permitted to submit bullet points; deadlines are extended, and regularly missed without penalty; extra time is given for all examinations.

The pace of change over the past decade has been astonishing, driven on by three forces: an administrative class that wants to minimise complaints, a subset of academics who actively resent the no-nonsense traditions of the university, and a proportion of students who will take the easiest path proffered. The result is a steady infantilisation of education, whereby challenging workloads are reduced, and robust criticism of bad writing and bad thinking is avoided. And now there is the prospect of the intense eight-week term being divided in two by a ‘recovery week’.

An even sadder development is that lectures now have to be filmed and made available online after the event. This constrains both lecturer and student materially: the experience in the room is compromised by the unknowably large third party who can watch whenever they want. Since ever fewer students now attend lectures, the very esprit de corps of the cohort is fading, and one of the university’s most special environments is threatened.

The university boasts that it is more ‘inclusive’ by the year, but there is no clarity about what the goal is. No one has made the case that box-ticking protocols materially improve the academic activity or excellence of the cohort. Instead, there is a complete lack of curiosity about what ‘diversity’ actually means, and about why there is over- as well as under-representation of certain ethnic groups in the university. Other than increasing raw numbers – 39 per cent of undergraduate students at Cambridge are ‘non-white’, compared to 22 per cent a decade ago – there is no coherent sense of what is being aimed for.

The character of the college as a micro-community of academics is being doubly subverted: from within, by the rapid growth of bureaucratic roles taken up by professional administrators, and from without, by a university seeking to centralise control and elide differences among the colleges.

There is, unsurprisingly, a major disengagement of academics from the university’s growing central administration. It was telling that a few years ago the authorities silently closed down the University Combination Room, the 14th-century hall in which academics could freely convene outside their individual colleges.

More alarmingly, there is a deeper-seated loss of trust in what the essential character of the institution is: elite, selective, competitive, rigorous. I have even heard academic colleagues agonise about whether it is ultimately ethical or appropriate that some students do better than others in examinations – academics doubting the very principle of grading by degrees.

The cleverest students sense that they are part of a faded spectacle, and I feel for them. They have neither the voice nor the medium to express that regret. Their own JCR committees face ever-declining levels of student engagement, as their (usually uncontested) ‘officers’ pivot to promote less relevant topics. Students vent their frustrations through the anonymous ‘confession’ pages on Facebook, where countless staff members lurk in the hope of gauging what decisions to make to pacify the most unhinged student protests.

All this I say of Cambridge. But these issues go right across the university sector, if somewhat less obviously in Oxford. By my reckoning, between the 74 colleges of England’s two ancient universities, there remain nine or ten sound institutions. I hope they dig their respective heels in and preserve the great traditions before they are irrevocably lost.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:03 11.11.2024 •

11:03 11.11.2024 •