The isolated Thule Air Base in Greenland is the only U.S. outpost that can monitor all of Russia’s missiles, but thawing permafrost is undermining the station, writes “Inside Climate News”.

Located just 900 miles south of the North Pole, Thule Air Base is now facing its most critical military role since the end of the Cold War, but global warming is hindering its mission: rising Arctic temperatures are thawing the permafrost on which it was built seven decades ago. From cracks in the 10,000-foot runway to the slanting of the floor in its banquet hall, the air base is crumbling.

Thule is the northernmost U.S. military base in the world and the first outpost that would detect an imminent attack by Russia on the United States. It is the only U.S. operation that can monitor all of Russia’s missile activity, sending a warning within 60 seconds to decision-makers at the Pentagon in Washington and bases in California and Colorado.

Constructed as a follow-up to a secret American mission in the region during World War II, Thule Air Base housed 10,000 personnel at its peak in the early 1960s. Today the total is at 650, a small number of dedicated Air Force and Space Force personnel who run the base’s radar and satellites. Scientists dip in for months at a time to conduct research.

Over the last seven decades, Thule has been through countless iterations.

In the beginning, it was a Strategic Air Command Installation, designated as a testing site to observe how weapons responded in extreme weather.

Later it became the stage for radio communications, and in 1959, the host for materials for a nearby top secret nuclear project called Camp Century.

The Ballistic Missile Early Warning System was added in 1961, and Thule became an Air Force Space Command base overseeing an array of U.S. satellites, launchings and cyberactivity in 1982.

Spanning 264 square miles, the base consists today of several dozen buildings, 65 miles of unpaved roads and the 10,000-foot year-round runway.

Russia’s emergence as a top player in the Arctic has stirred strategic concern, especially as the Kremlin’s military decision-making came to be seen as more volatile and dangerous. In 2014, Russia began expanding the construction of airfields in the Arctic and refurbishing older sites.

Greenland also sits within what is known as the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom Gap, a triangular strategic route that the United States has monitored by submarine, satellite and other means since the advent of the Cold War. The area comprises a 200-mile stretch of ocean between Greenland and Iceland and a 500-mile gap between Iceland and Scotland.

The GIUK Gap is currently the main point of entry into the Atlantic Ocean for Russia and China, and the only thing standing between Russia’s powerful naval fleet and North America. Thule plays a key role in securing those approaches to North America: Any move the Russians make, the base is watching.

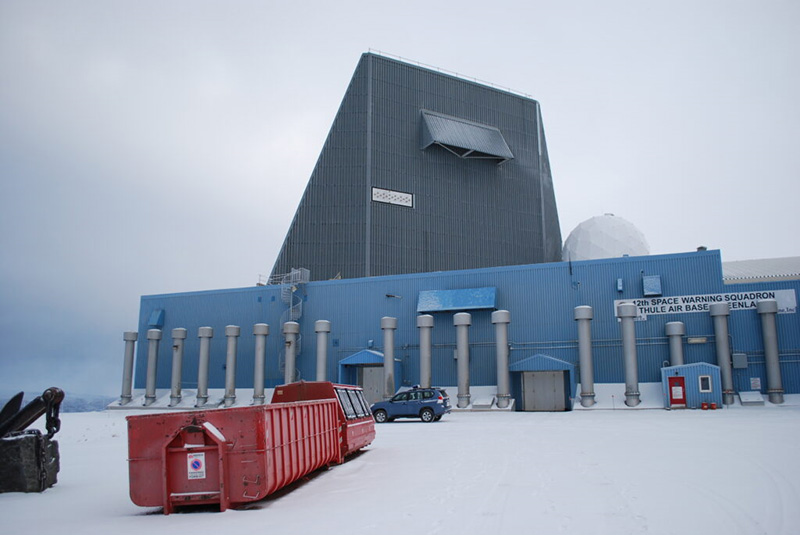

Thule Air Base’s 12th Space Warning Squadron, where ground-based radar is used for missile warning, missile defense and space surveillance.

Thule Air Base’s 12th Space Warning Squadron, where ground-based radar is used for missile warning, missile defense and space surveillance.

Photo: Inside Climate News

“We cover the entirety of Russia,” said Lt. Col. April Foley, who oversees the radar at Thule. “We need defenders at all times.” “Defenders,’’ a popular Air Force moniker invoking that branch’s mission readiness.

Thule has been critical to American security since 1953. Constructed in just 60 days, it was touted as an engineering masterpiece: Buildings were drilled into the ice, with the permafrost serving as a substitute for cement.

Over time, problems began to emerge. The base’s buildings had been designed to minimize any thawing effect from the heat within them: Structures that had to be at ground level, like aircraft hangars, had two stories with cold air circulating between them, and the others were well above ground. As long as the 1,600-foot-thick permafrost stayed frozen, the buildings were safe.

But the engineers could not anticipate how dramatically climate change would affect the permafrost. In 2009, the summer’s unprecedented heat caused some buildings to sink into a slushy mix of water and gravel, and vehicles became trapped on the base’s soggy unpaved roads. Last month, new research showed that the first decade of the 2000s was the warmest 10 years on record in Greenland in at least 1,000 years.

Building on permafrost involved “a lot of experimentation,” said Col. Brian Capps, the base’s commander. “The facilities we’re seeing with sinking foundations and things like that is because we were experimenting.”

Problems can take months to fix. Over 60 miles from the nearest town, the base is so remote that all of its supplies must come in by aircraft or through the port, open from just July to August every year.

Last April, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a report lambasting leaders at its six Arctic and sub-Arctic military bases for failing to carry out climate contingency planning as required by U.S. law. Those leaders, investigators found, “did not comply with requirements to identify current and projected environmental risks, vulnerabilities and mitigation measures.”

Base leaders were too focused on current conditions, it continued, and failed to analyze long-term climate threats. The report also faulted the Pentagon itself for providing inadequate guidance and resources for assessing the implications of climate change.

The Department of Defense manages over 1,700 global military installations along coastlines, areas that have already suffered the effects of climate change.

Second only to Antarctica in scale, Greenland’s ice sheet covers 80 percent of the country and is up to two miles thick. Scientists believe the ice may be 18 million years old. Antarctica excluded, the ice sheet is four times the size of all of Earth’s other ice and glaciers combined.

According to the World Meteorological Organization, however, Greenland lost enough ice on one day alone last summer to submerge the entire state of Florida in two inches of water. Already the largest single contributor to rising sea levels, with a millimeter added every year, the island’s melting ice is expected to increase the global sea level by at least 11 inches by the end of the century. If the entire ice sheet melts, it would add 24 feet of water to the sea level, flooding every major coastal city in the United States, from Miami to San Francisco.

Based on a reading of publicly available base contracts, Thule is its most expensive overseas base to operate, a drain of more than $100 million a year. That is 10 times the amount needed for the average Air Force base. Much of the expense is associated with the remote location, given that all of Thule’s supplies must come in by aircraft or the port open a few months a year.

With the United States now making up for lost time on the climate challenge, the cost is set to soar.

…Hmm – even the climate is against USA.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:46 02.03.2023 •

10:46 02.03.2023 •