Donald Trump was complimentary when he received Shigeru Ishiba in the White House this year, but there are rising fears that the US president and Japanese prime minister are not seeing eye to eye.

Pic.: FT montage

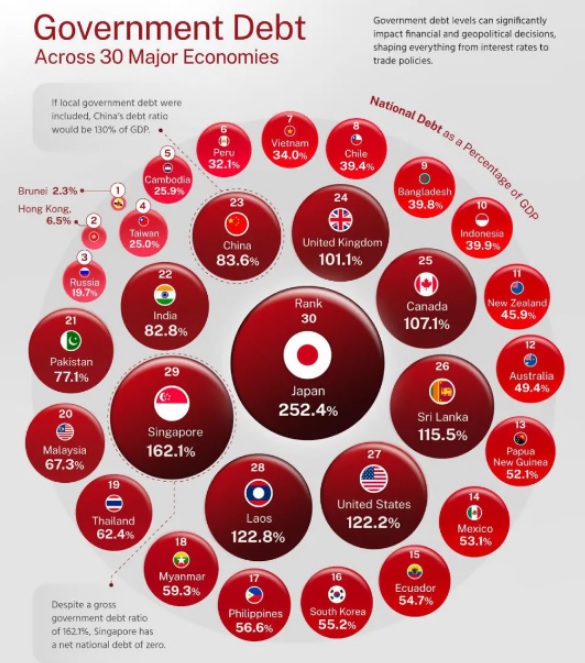

At the start of July, days before the US was due to impose large tariffs on $150bn of imported Japanese goods, President Donald Trump vented his frustration with America’s biggest direct investor, its largest host of military forces and the biggest foreign holder of its debt, ‘The Financial Times’ writes.

“I could send [a letter] to Japan. ‘Dear Mr Japan, here’s the story…’,” Trump told a television interviewer, after months of negotiations had failed to yield the quick, amicable and example-setting trade deal both sides initially thought possible.

For senior officials in Tokyo, the “Mr Japan” line jarred horribly with the “we love Japan” rhetoric with which Trump had welcomed Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba to the White House just a few months earlier.

But some fear it symbolises a descent into the worst crisis in a quarter-century for a bilateral relationship that has helped underpin the postwar global order.

There have been rough patches in that alliance before: Richard Nixon’s courting of China, US lawmakers smashing Toshiba radios on the steps of Congress after the company sold submarine technology to the USSR, and the 1990 Gulf war.

But suddenly, there are signs of a more fundamental fragility. Trump’s hard-headed approach and Japan’s failure to adapt to it present a rising risk, say senior officials on both sides, of a destabilising conflation of security, trade and currency issues.

“The challenges go deeper than any single figure in the administration,” says Christopher Johnstone, a former White House official now at The Asia Group consultancy. “There is a sense in Japan that for the Trump team, nothing is sacred and everything is transactional.”

The absence of any preferential status in trade talks was confirmed on July 7, when Trump posted his trade terms letter to Japan on social media before it had even reached Ishiba.

The missive was largely identical to ones sent that day to the leaders of 14 other countries, including relatively peripheral ones such as Kazakhstan, Laos and Serbia. There was no recognition of Japan’s status as a key Pacific ally, no reward for being first to the negotiating table. It was, said Ishiba, “deeply regrettable”.

Japan should have seen that coming, according to one person close to both sides of the trade negotiations. Japan lobbied for a total exemption from tariffs, a stance that critics of Ishiba say ignored Trump’s underlying agenda of trade rebalancing and his core belief that foreign trade surpluses are evidence of intrinsic unfairness.

Fears are growing that the escalating trade crisis will directly affect the balance of security across the Asia-Pacific region. “The strategy is you isolate the isolator — China — and you do that by having no daylight between the US and Japan,” says Rahm Emanuel, who served as US ambassador to Japan under the Biden administration.

“So why create unnecessary daylight? If Japan and the US are aligned, all the other pieces — India, South Korea, Australia, the Philippines, New Zealand and others — quickly join up, leaving China as the odd man out,” he adds.

Dozens of current and former officials on both sides have told the FT, that the alliance as an institution will survive — but that an era-defining reset is now inevitable, and it will be a litmus test of what it means for anyone to be a friend of the US in 2025.

“US-Japan relations are in their worst state perhaps in a generation, going back as far as the late 1990s when there was intense trade friction and fundamental questions about the shape of the alliance after the cold war,” says Johnstone.

The sudden uncertainty around the US-Japan relationship has coincided with a moment of unusually acute peril for Ishiba’s Liberal Democratic party, which has dominated Japanese politics since the end of the second world war.

Inflation, immigration and trade uncertainty are all weighing heavily on Ishiba. The LDP lost its majority in the lower house of parliament last October, leaving it dependent on coalition partners and putting the prime minister’s job at risk. It could lose its majority in the upper house after elections on July 20.

Attempts to redress that impression, at home and in Washington, have produced some unusually vehement rhetoric. “We need to make more efforts to become less dependent on the US. It would be a problem if we came to regret that they were telling us to do what they say because of that dependence,” Ishiba said on national TV last week.

But the country looks increasingly unable to fight for its national interest on anything other than Trump’s terms, say veterans of previous US-Japan trade negotiations.

When it comes to Japan, Trump may be unpredictable in his tactics, but he is remarkably consistent in his doctrine. In a now famous 1987 interview with Larry King, Trump the real estate baron elucidated his resentment of the way Japan had been “ripping off” America.

Trade was not free, said Trump, despite appearances to the contrary, adding that friends of his trying to do business in Japan faced “impossible” challenges. The positioning of military bases on Japanese soil, he added, meant Americans were in effect paying to defend the “wealthy money machine” of Tokyo.

“By the way, I like the Japanese very much… I like them very much but they laugh at us,” said Trump, whose comments came at a time when US concerns about a weakened currency helping to drive Japan’s soaring exports were still acute.

Four decades on, many of those views appear intact: Trump has pushed Japan to raise its defence spending, regards its $68.5bn trade-in-goods surplus with the US as hard evidence of unfair trading practices and non-tariff barriers, and has described the country as “spoiled”.

“What is happening to Japan highlights the way that Trump looks at the world,” says David Boling, the Japan and Asia trade director at Eurasia Group. “Trade deficits are more important to him than whether you are an ally. Trump 2.0 is Trump 1.0 on steroids, and the president is taking a long-held view on tariffs to the maximum.”

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

9:09 16.07.2025 •

9:09 16.07.2025 •