Is Britain ready to fight with Russia? Hardly… But it wants this war! Therefore, as is usually the case, London is using Russophobia as a tool to set other European countries and their peoples against Russia. This is how they act in Ukraine and other sites.

‘Financial Times’ published another article pushing countries that are on Russia's borders to a military clash with it. Doing dirty work with someone else's hands London believes that in the event of a war the island of Britain will remain intact. Hardly again…

And this is a false and provocative claim that Russia is preparing for war with NATO. But they in London have no other more meaningful pretexts.

A pathetic parody of Britain's former might that has been irretrievably consigned to history…

A pathetic parody of Britain's former might that has been irretrievably consigned to history…

Pic.: ‘The Telegraph’

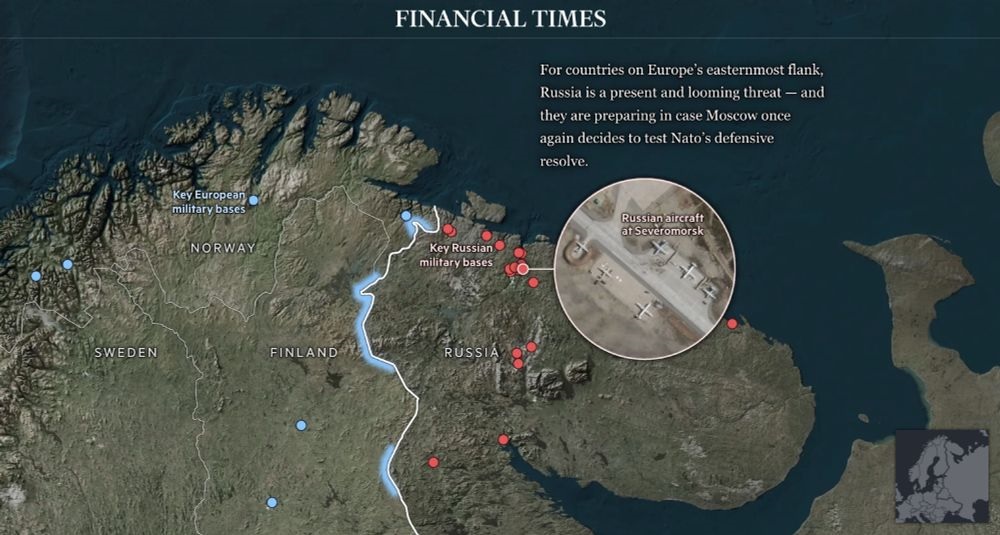

For countries on Europe’s easternmost flank, Russia is a present and looming threat — and they are preparing in case Moscow once again decides to test Nato’s defensive resolve.

With Russia strengthening its military presence in the region and US commitment to the European defence pact wavering, the alliance and its members are racing to build defences.

Countries are bringing back conscription, acquiring more weaponry and fortifying their borders. Finland has accelerated construction of a 200km fence and boosted surveillance and patrols.

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are building a Baltic defence line made up of concrete bunkers and anti-tank ditches along a 600-mile stretch of border with Russia and its ally Belarus — the most exposed part of NATO’s eastern frontier.

Lithuania is particularly vulnerable. It is bordered to the south by the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad and the Suwalki gap — the only territory connecting the Baltic states to the rest of NATO.

Poland is constructing €2.3bn worth of defences to form an ‘East Shield’ — the largest attempt to strengthen the country’s eastern border since 1945.

The outcome there will determine what Moscow does next, warns ex-NATO head Anders Fogh Rasmussen. ‘If Putin gets any success in Ukraine, he won’t stop there.’

The camo-clad attackers swarm through the dense Finnish forest, rifles cocked. A frontline order is quickly given to call in an artillery strike, and then pandemonium breaks out in this wooded area close to the Russian border.

The scene is a war game, like dozens of others playing out every month, taking place this spring between conscripts for Finland’s Border Guards.

“In Finland, defending your country is a really important value,” says Milja Sandhu, a rare female conscript. “Everyone has requested to be here and motivation is really high. It might be more realistic in times like these.”

Her platoon companion, Kasperi Luoto, describes it as “a calling”. “Finland has a really strong willingness to protect itself,” he says. “The war in Europe has changed the way people want to serve.”

Asked how the exercise has gone, he looks sheepish: “You get a little excited and run into enemy fire.”

The subtext of this war game is deadly serious. Finland’s entry into Nato in 2023 more than doubled the defence alliance’s border with Russia to almost 2,600km, stretching from the Arctic down to Belarus.

While Moscow is currently tied up with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many along this frontier expect Russian President Vladimir Putin to one day turn his attention to NATO’s eastern flank. The Russian economy is already geared towards conflict and Putin’s imperialist ambitions may mean it goes on to look for conquest elsewhere.

NATO secretary-general Mark Rutte warned last month that Moscow could be ready to use force against the alliance “within five years”. “Let’s not kid ourselves, we are all on the eastern flank now,” Rutte said in a speech.

While US President Donald Trump reassured allies he was “with them all the way” on arrival at the summit, he had spooked European capitals hours before with a suggestion that the military alliance’s mutual defence pact, known as Article 5, was open to interpretation.

His presidency has raised questions about how strong and long-lasting the American security guarantee will be, placing Europe’s defence capabilities under the microscope in a way not seen in decades.

Many of the eastern European NATO countries are rushing to increase their defence spending to fill gaps in military capabilities under the pressure of both Russia and Trump.

NATO allies reaffirmed their “ironclad commitment to collective defence” at the alliance’s summit as well as agreeing to increase defence spending to 5 per cent of GDP over the next decade, although there is some flexibility regarding how much will be committed to frontline defence. Spain secured a controversial opt-out by promising to meet the NATO capabilities goal at a lower cost.

But some question whether the extra investment will come quickly enough.

Military experts say Moscow’s interest in border states is different to how it views Ukraine. Rather than a full-scale invasion, Putin will likely test whether Nato would or could respond.

“For Russia, the strategic goal would be to break NATO; it’s not about acquiring a bit of land in the Baltics or elsewhere,” says Kristi Raik, director of the International Centre for Defence and Security in Estonia.

It is a different matter in the three Baltic states. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are seen as the most vulnerable region to a potential Russian attack.

It is only about 200km from the Russian border to the Baltic Sea, making a Finnish-style tactical retreat and bringing in reinforcements tricky. Then there is the 100km-long Suwalki Gap, which links Lithuania to Poland but is sandwiched between the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad to the west and Belarus to the east.

“Unfortunately, we are not so strategically deep as Ukraine, and this is a problem,” says Gitanas Nausėda, Lithuania’s president, explaining the differing geographies. “So we are talking about defending our territory for a certain period and then expect that reinforcement will come.”

Being in NATO for the past 20 years means that the Baltics feel safer than they have for a long time. “We are more secure than we have been for centuries because we have allies, because we have Article 5,” says one senior Baltic official.

Nato’s increasing presence in the Baltics can be seen at NATO’s large Pabradė training ground, close to the Russian border in Lithuania, with satellite imagery showing new structures built between 2022-25 and higher levels of activity.

Lithuania’s Nausėda says that the Baltics need to have a plan a, b, and c as questions swirl about the US commitment to Europe. A senior Baltic official is blunter: “The Americans are leaving. We all have to wake up to that and deal with it.”

The Baltics and Poland to their south are all busy reinforcing their borders with Russia and Belarus. The Baltic Defence Line, now under construction, consists of border fences, bunkers and dragon’s teeth — concrete blocks designed to stop tanks.

Each Baltic country is boosting its own military capabilities too: Lithuania wants to have a national division of 17,500 troops by 2030; Estonia has a wartime strength of about 43,000 troops; Latvia has reintroduced conscription. All three countries are also working together to develop joint mass evacuation plans.

Poland’s proximity to the war in Ukraine and its long border with Belarus make it a key bulwark against any future Russian aggression.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk has been one of the loudest advocates of increased military funding by EU member states and his country is currently proportionally the largest defence spender among NATO allies.

Tusk, who last month survived a vote of confidence in his leadership, has proposed more than doubling the country’s army to 500,000 troops and establishing a system of military training for all adult men by the end of the year.

Along with the Baltic nations, Warsaw has also been buying long-range missiles capable of striking targets inside Russia.

“It’s much easier to destroy the nest than kill the birds in the air,” says Estonia’s defence minister Pevkur.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:32 04.07.2025 •

11:32 04.07.2025 •