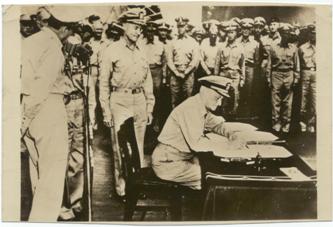

Asiatic-Pacific front. Korea, 1945. The Japanese Imperial army had been defeated. The Korean peninsula had just been divided along the 38th Parallel into two zones of influence: American and Soviet. The Allies guarding the border were so close to each other; the mutual interest was as intense as at the Elbe in Europe, though it was not as broadly publicized.

Caption on the back of this photo: "Meeting between troops of the 7th Infantry Division and the Russian Border Patrol, just a few feet of the 38 degrees Meridian." (Photo is borrowed from the US National Archives)

The National Archives stores a photo, taken in Korea on September 12, 1945. It shows soldiers and officers from the American and Soviet armies: smiling happy people are shaking hands and hugging each other. All those encounters, whether accidental or arranged by a cameraman, were indeed very cordial. Soldiers and officers from the Allied forces were very curious about each other. What do the folks on the other side look like? Are they friendly? What kind of people are they? There was a lot of meaning to those interactions; on the background of global historical events, they were so very personal at the same time.

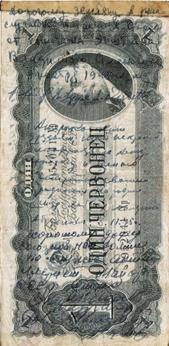

Those who were lucky to meet face to face showed their enthusiasm to the fullest. They shook hands, cried and laughed, hugged and patted each other on the shoulders. They exchanged little souvenirs – whatever they happened to have – pieces of their military insignia, belt buckles, wrist watches, even wedding rings. Some would use a paper money, a dollar or a ruble, to write down their names, addresses, and best wishes. There was meant to be a meeting, a correspondence, a personal contact. Indeed, years after the war, Alexander Silvashko and Nikolay Andreev met with Bill Robertson; Ivan Numladze met with Byron Shiver; Vladimir Kabaidze met with Frank B. Parent. As a matter of fact, V. Kabaidze and F. Parent exchanged paper currency where they wrote down their names and addresses. That's how they found each other in 1987.

The Korean paper bill, both sides.

Here is the story unveiled by a Korean paper bill, signed by four American officers on November 3, 1945. (What happened on November 2-3, 1945, was told by late Vladimir Epstein, a Soviet Army officer who served in Korea at that time. He was then commander of a Soviet Infantry regiment patrolling the area.)

It was a gloomy morning of November 2, 1945, at the 38th Parallel just north of the Korean region of Yang Yang. Commander Vladimir Epstein heard the rattle of an airplane engine. A small airplane was circling a clearing in the woods, looking for a landing. The plane was not Soviet, and Vladimir Epstein ordered the soldiers to quickly surround the area. When the plane landed and four Americans stepped out of it, the whole incident became a matter of a friendly visit! Commander Epstein invited the Americans to follow him.

He led the guests to a small house in a peach orchard. Soviet soldiers quickly laid the table. The Allies raised their glasses to the long-awaited Victory and the long-lasting friendship between the two great nations. The next morning the Americans toured the barracks of the Soviet soldiers. Neatly made bunk beds and stacks of shiny rifles produced a favorable impression on the guests. After lunch they all went to see the shooting exercises at the range.

Standing by the airplane just before their departure, Americans gave Epstein something that he would keep for the rest of his days: two pieces of paper currency which happened to be an American paper dollar stamped "Hawaii" and a Korean bill with a traditional floral design on one side and a portrait of a historical figure on the other. On it, all the Americans wrote down their warm wishes and signed their names. Commander Epstein, in his turn, gave the Americans Russian 5-ruble bills that had a picture so appropriate for the occasion: a pilot standing next to his war-time airplane. Someone from Epstein’s group came up with more Soviet currency which was signed by those present and given to the Americans.

The plane with the American friends slowly steered around the opening to get more room for take-off; a minute later it was airborne. While still visible, it rocked side to side, as if waving good-bye and disappeared in the direction of Seoul.

Vladimir Epstein with his wife Tatyana. 1945.

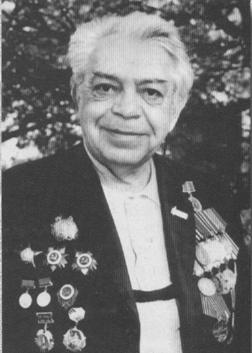

Vladimir Epstein.

For Vladimir Epstein it was his fifth year of war. Born in 1922, he faced his first battle in June 27, 1941 at the age of 19. He was wounded twice. He fought at five major fronts in Europe, and later was relocated to the Pacific. For his personal courage and resolute leadership as a battalion commander in Korea, Captain Vladimir Epstein was decorated with the honorable Order of Alexander Nevsky. It was the fifth military award of a 23-year-old commander. It is a fact that out of 100 Soviet soldiers and officers born in 1922, only two survived the war. Captain Epstein was one of them.

Vladimir Epstein was brave, decisive, and untraditional in many ways. In 1945, when the fighting at the front was over, he delegated one of his soldiers to the Siberian city of Kemerovo where his wife Tatiana lived and worked as a bookkeeper. His "orders" were to bring Tatiana to him in Korea. For seven days in a row Tatiana was refusing to go. But the soldier was not leaving, repeating the Commander’s words, "He said, don’t come back without my wife." On day 8, the woman gave up. Their daughter Irina, 70, says with a shy smile, "I was conceived in Korea…"

The wartime passed. Vladimir Epstein got back to his home in Moscow, USSR. He knew that he needed a civil profession, so he went straight to school. Having graduated from the Moscow Printing College, he worked for several newspapers and the magazine Border Patroller. He was a talented person with excellent writing skills and a great sense of humor. All this put together made it possible for Vladimir to write libretti for several musical comedies that were played on stage in the theatres of the Russian cities of Novosibirsk and Yakutsk, as well as in Lodz (Poland) and Varna (Bulgaria).

Alexander Nevsky medal.

Vladimir Epstein lived a long and full life. He had a charismatic outgoing personality and had lots of friends. He was very active in the organization of the Veterans of the 323 "Bryansk" Infantry Division and was its Vice President. He put together and edited a book of memoirs of the WWII soldiers "There March the Soldiers…" which was published in 1993. In the 1990s he was among the founders of the Union of the Alexander Nevsky Order.

Vladimir Epstein never forgot his war time friends; he kept and cherished the Korean bill with four signatures on it. He wanted to learn about the fate of the four men whom he met back in 1945. In 1990, a 68-year-old veteran asked for assistance at the American Embassy in Moscow. A secretary at the Embassy was nice to Vladimir; she listened to his story, made a photocopy of the Korean banknote, and promised to help. Now, having spent three years in research, the authors of this article know how naïve it was then to expect any positive results of the search. It could not be quick, it could not be easy. The Internet was just emerging. The Embassy employee could not do anything; she only gave hope.

Veteran Vladimir Epstein. 2000s.

All this time since the War, Commander Epstein carefully and lovingly stored the Korean bill and the American dollar. He never did learn about the four men. This is our attempt to fill the gap and write an unwritten page in history.

Vladimir Epstein passed away in 2004 and was buried at the Donskoy Cemetery in Moscow, leaving behind his second wife Galina Prokopchuk, a retired operetta singer, his daughter Irina Nikiforova, the head of a laboratory at the Electro-Mechanic Research Center in Moscow, and his granddaughter Natasha, a clothes designer.

Vladimir Epstein told this story to Alexey Abramov, his friend in college, where they both studied after the war. It made a deep impression on Abramov. Five years after Epstein passed away, Abramov published the story in a Russian magazine. I got a chance to read it. The story struck me as being one of those we don’t hear often about the war. It was not about powerful advances of huge armies, flying cannon balls, treacherous torpedoes and sinking ships. It was certainly not a scenario for an action movie. It was about actual people who constituted those armies and contributed to the Victory, but whose identity was often swallowed by the enormous size of the military machine in action.

My other thought was that this story ought to be translated into and published in English, because four American officers are part of it. If I am lucky, the publication may find its way to the veterans themselves, or to their families, friends. It is never too late to say warm words of love and gratitude to our veterans.

I got in touch with Mr. Abramov by phone. He resides in Moscow, Russia. He is a passionate and dedicated historian and a WWII veteran himself. He gave me the permission to translate the article into English and use the electronic image of the Korean bill. The longer I looked at the bill, the more I realized that there is more to it than just translating Abramov’s original text. I felt I had to at least transcribe the signatures. From that time on this story and the signatures took over my life – for almost three years!

I started working with the image of the bill. The words have faded with age. The signatures are even harder to read because of the darker and uneven background of the bill itself. I spent hours, days, weeks examining the signatures with a magnifying glass, playing with the possible letter combinations. Eventually I got stuck seeing the same characters – whether or not they were right. I started asking for "a fresh pair of eyes" anybody who would listen to me. Some people would try, but nobody, just like me, could guarantee the accuracy of the results. Many a time I lost hope to regain it again and again. Months of seemingly never-ending effort finally yielded the names under the short messages – one by one.

It took a long time to decipher the name of the person whose energetic note "Good Luck, Captain!" gave this article its title. I owe this discovery to my friend, an elementary school teacher Celia Anklesaria and her hard-to-match patience and painstaking attention to details. At first she figured that the line read "John J Gh--gher Jr", but the letters in the middle were still a puzzle. However, it was obvious that the stubborn letters were short: their elements did not go either above or below the line. Celia was putting together possible combinations of two letters, consisting of over a dozen of "graphically short" characters of the alphabet. She ran the results against the Internet search. The effort finally brought a breathtaking hit. She sent me an e-mail, "I think I found the officer’s son. His name is John J. Ghingher III!"

John J. Ghingher, Jr.

The web page stated: John J. Ghingher III, Attorney in Baltimore, MD. It was so unbelievably close and, at the same time, almost surreal! Feeling a bit nervous, I picked up the phone and dialed. The secretary answered the phone and asked what kind of business I had. I replied that it was a private call and left my phone number. Mr. Ghingher kindly returned my call at the end of the day. I introduced myself and offered him what I would consider to be a very unusual question. "Is it possible that your father was in Korea in 1945?" "Yes" was the short answer, the answer I longed for, and yet it proved to be shocking. I was so happy that I found that living thread connecting today with the events of November 1945!

John J. Ghingher, Jr. June 1942.

I explained to Mr. Ghingher that in my possession I had a Moscow-published article, the content of which I wanted to share with him. It was, – I went on, – about four American officers that flew a small plane, landed just north of the 38th parallel, and eventually made friends with a Soviet officer. Mr. Ghingher readily answered that he remembered his father talking about this episode, and that the four men did not expect such a warm welcoming: at first were even afraid that they would be apprehended. To their surprise, it turned out to be a wonderful celebration of friendship between the allies. Unfortunately, his father, Mr. John J. Ghingher Jr., had passed away.

Mr. J. J. Ghingher III kindly gave me his email address and I forwarded the image of the Korean bill to him. His answer came back almost immediately, "I recognized my father’s signature right away!" The following day he emailed the text of the article and the image of the Korean bill to his brothers and sisters who got very interested, too. Unfortunately, neither Mr. Ghingher nor his siblings could provide more information about that day in 1945, or the names of the other three officers.

Major J.J. Ghingher is receiving the Bronze Star Medal. Korea, 1952.

Now that I found a live thread, the Ghingher signature obtained a special aura. I became engulfed by the story; it took over me. I started on a journey along the Internet roads, some paved, some barely seen. I went to local libraries and the National Archives. And every time I made a discovery, the abyss of the unknown looked deeper and wider. Deciphering the signatures no longer was my destination. I wanted to know about those four men; with every little step of mine they became more and more real to me. I kept on going.

What I learned from the public sources about the Ghinghers, made me believe that John J. Ghingher, Jr. (1916-1980) may have inherited his inner strength and fearless attitude towards life from his father John J. Ghingher (1893-1967) and grandfather Jacob Ghingher (1849-1923). Even my modest-scale research showed that both the father and the grandfather had a great deal of character and personal courage.

From the US Censuses of 1860-90s I learned that Jacob Ghingher (grandfather) was born in England in 1849, and at the age of 6 was brought to the United States. He came from a farming family, and soon after his arrival to the U.S. started working on the farms of Caroline County in Maryland. He knew hard work, and did not mind it. He also knew how to read and write. On January 3rd, 1893, a 43-year-old Jacob and his 35-year-old wife, Araminta (Minnie), had a baby boy and named him John Jacob.

Further research of the publically available documents revealed that John Jacob Ghingher (father) received a much better education, having obtained a Law Degree. At just over 20 years of age, he already worked for the State of Maryland as a bank examiner, then a commissioner at a bank, rising later to the position of a Second Vice-President of a bank and later, in 1942, a member of the Board of Directors of the Central Insurance Company in Baltimore, MD. As an attorney, he also argued many cases in Maryland Courts in 1930-40s.

Bronze Star Medal.

On December 6, 1916 he and his wife Ida had a son, whom they called John J. Ghingher, Jr. Their son followed his father’s footsteps. After high school he went to the University of Maryland School of Law where he exceeded both in studies and sports. In 1941, at the age of 25 he graduated with a Degree of Bachelor of Laws.

In June 1942, John Jr. put on a military uniform. He chose to be in the artillery. The war, following its course, picked him up in its whirlpool with millions of others. In 1945 John Jr. was fighting at the Asiatic Pacific front, helping bring down the power of the Japanese Imperial Army and freeing Korea. That’s where on November 2nd he and three other American officers flew just North of Yang Yang and had that unexpected encounter with the Soviet officer Vladimir Epstein. The episode was memorable: the veteran remembered it.

John J. Ghingher, Jr. went to war twice. During the Korean conflict of 1950-1953 he was back in Korea again. The National Archives store pictures of him in 1952 as Lieutenant Colonel, a staff officer of the 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd US Infantry Division. On June 30th 1952 John J. Ghingher, Jr. received his Bronze Star Medal "for bravery, acts of merit, or meritorious service" and was given orders to rotate back to the U.S.

Back at home, John J. Ghingher, Jr. practiced law in Baltimore, MD. He acted as an Assistant City Solicitor in the "Stadium Case" in 1948. He served as a General Counsel for the Baltimore Metropolitan Transit Authority, creating a chapter in Maryland Manual 1967-1968. He worked as an attorney in the United States Court of Appeals, dealing mostly with cases concerning large industrial and recreational properties. He and his son also worked together on a number of cases and projects, including a manual A Contemporary Appraisal of Condemnation in Maryland, which was published in 1970 and was highly praised among the specialists.

John J. Ghingher, Jr. passed away in 1980 at the age of 64.

The other side of the bill has one note, "From one Friend to another. Philippe J. Durette."

Philippe Durette.

Reading this name was much less of a problem. The first name left no doubt as it was spelled out so eligibly: Philippe. The last name definitely had the letters D---tt-, maybe Durett-; as to what the last letter could be, there were very few possibilities. Duretti? Duretto? Durette! The first page of the Google search on "Philippe Durette" brought his... obituary.

Purple Heart Medal.

The obituary outlined the life of this man. It mentioned that he was a WWII veteran; he was born in Fall River, MA and died in Swansea, MA. He had two daughters, Diane and Christine, and six sons: Richard, Gerald, Daniel, Roger, Albert and Michael. Hence, the next leg of my search brought me to the Massachusetts online White Pages. I was looking for the Durettes in the neighborhood of Swansea and Fall River.

The first phone number I found was that of Philippe’s son Gerald. Gerald’s wife Marie answered my call. I am very thankful to her for being so nice and open with me. Later in her email she wrote to me that she located Philippe’s Purple Heart medal and copied the accompanying information: "Purple Heart GO# 214 Hq 7th Div. 22 Nov. 45 Asiatic Pacific Theater Campaign, Ribbon Victory Medal." It also stated that it was awarded for the battle for Ryukus. This confirmed that indeed Philippe Durette served in the Pacific: with the 7th Division he was fighting the Japanese for the Ryukus Islands, where the major American offensive in the spring/summer of 1945 was taking over Okinawa. Maybe the other three Americans also belonged to the 7th Division? Just a guess... Meanwhile, Marie suggested I call Durette’s daughter Diane St. Laurent.

Philippe Durette, September 1944.

Conversations with Diane were extremely pleasant and fruitful. She shared many precious memories with me. She recollected that Philippe did not like to talk about the War. They say that many veterans, who have gone through tough and gruesome situations, avoid these conversations. Those memories can be too vivid and too emotionally disturbing. Diane was always interested in her father’s past. She even visited Fort Ord in California where he had his boot training, and later went to see Pearl Harbor. By doing this she proved to her father how genuine her interest was. At times, Philippe would mellow and talk to her. She said that he did mention Korea on the 38th Parallel: the episode passed the test of time, his memory retained it!

Here is what I learned from my phone and email conversations with Diane St. Laurent about her father Philippe Durette.

Philippe Joseph Archilles Durette was born on January 1, 1921. In 1944, at 23 years old, he was a married man, had a son, and his wife Yvonne was expecting for the second time. Philippe was driving a truck for a living. He was sure that he would be drafted and was afraid he would end up on the water, with the Marines. So he and his half-brother Adrille Boucher decided to join the army.

Unidentified American soldiers. Okinawa, 1945.

Photo is borrowed from the Internet.

On September 25, 1944 Philippe Durette enlisted in the Army. On the same day his photo was taken. His newborn baby-girl Diane was just 10 days old. Her mother placed a photograph of Philippe on the piano, and every time they would pass it, she would point to it saying it’s Papa. Two years later, when Philippe Durette returned home, Diane refused to go to him, though her mother kept saying he was her Papa. "He is not. There's my Papa," objected little Diane, pointing to the photo on the piano.

After the military training at Fort Ord, CA, Philippe Durette was deployed overseas, to the Asiatic Pacific Front. His route went via the transitional base in Hawaii, where he spent a couple of days. Diane remembers that he mentioned how much he wanted to see the island, but there was neither time nor opportunity.

New circumstances of life brought new acquaintances. Durette was a man with a happy disposition, and he quickly made friends with two other men, Donovan and Donnelly. The three men were referred to as the "three Ds." During the assault on Okinawa in the spring/summer of 1945 the 7th Infantry Division was in the heart of action. One day the "three Ds" were under fire and were running for shelter, when suddenly a Japanese soldier jumped out from the woods and fired at Philippe’s two best buddies. They both died. Durette got shrapnel wounds in his legs. Crippled by the agony of pain, he still managed to shoot down the enemy. On November 24, 1945 he was awarded the Purple Heart medal. At that time he was already in Korea, where three weeks earlier he and three other officers had a memorable encounter with the Soviets at the 38th Parallel.

Philippe Durette with his wife Yvonne, 1990s.

In 1946 he was discharged from the army and returned home to see his family: his wife Yvonne, his son Richard and his two-year-old daughter Diane. He got back to his job as a truck driver at the former Hemingway Trucking Company where he worked for over 30 years till he retired in 1974.

Philippe Durette fought his last battle with cancer and passed away in his home in Swansea, MA on November 8, 2005 at the age of 84. He left behind a large family: two daughters, six sons, a brother, nineteen grandchildren and twenty-seven great-grandchildren. Mr. Durette’s obituary says that he was a communicant of Saint Michael Church in Swansea and was a Marion Medal recipient in1985, member of the Teamsters Local 251 in East Providence, RI American Legion Post #303 in Swansea, Swansea Police Association, Swansea Volunteer Fire Department Company # 3, Association of Canadian Americans, and Saint Anne Court chapter. He was buried with Military Honors at Notre Dame Cemetery in Fall River, Bristol County, Massachusetts.

Let me take you to another note on the Korean bill that was written by a person with a great sense of humor, "The American who by mistake came to Yang Yang North of 38° but now is sorry to return to his own army. Charles Ernest, Major U.S.A."

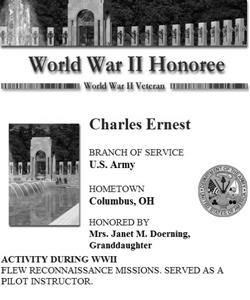

Charles Ernest

To correctly read this name off the banknote was probably the least of a problem. To find a veteran with such a common name proved to be a major task. There were just a couple things I knew for certain about this man: Charles Ernest was a Major as of November 3, 1945, and at that moment he was in Korea. Using the information off Philippe Durette’s Purple Heart medal, I assumed that all the men may have belonged to the same military unit, that is: 7th Division, 10th Army, XXIV Corp. They may have gone together through the battle for the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa) in the Pacific.

The result of the White Pages search was overwhelming. After talking on the phone to a couple of dozen namesakes of Charles Ernest and not finding a trace of the one I needed, I gave up: sifting through hundreds of names without any reference to people’s age or veteran status was akin to looking for a needle in a haystack.

The Library of Congress website looked promising: its Veterans History Project provided information on military personnel for the period of World War II. In this database, three people had the combination of "Charles" and "Ernest" in their names. One of them took my breath away: he served in the same 7th Division, 10th Army in (among other places) Japan, Okinawa Island (Ryukyu Islands). However, his highest rank by the time of his discharge from the Army was Private First Class. Wrong person.

WWII Memorial Registry

The Census of 1930 shows a Charles Ernest born in 1920 in South Carolina. A different snapshot states that Charles Ernest was missing in action in 1945 in Germany. Is it the same person?

The Second World War Memorial downtown Washington, D.C. honors millions of Americans who served in the Armed Forces, hundreds of thousands of those who died, and all those who supported the war efforts back at home. Here, among the sixty-one entries with the last name Ernest, two veterans also shared the first name, Charles. The information in the Memorial Registry, scant as it is, states that one of them "flew 50 missions out of Southern Italy over enemy territory" while the other "flew reconnaissance missions and served as a pilot instructor." The person I was looking for could be either of them.

A week spent in the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, cleared a lot of uncertainties and the kaleidoscope of information started to look like pieces from the same puzzle.

Charles Ernest, 1952.

Charles Ernest was born on August 10, 1907 in Columbus, Ohio. During the Second World War he was a Field Artillery pilot, flying air observation post aircraft for the field artillery. In the Southwest and Central Pacific Area (Okinawa) in 1945 artillery air officers were instrumental in bringing up a few important innovations to air observation posts. The process and its impressive results are described by Dr. Edgar F. Raines, Jr. in his book Eyes of Artillery. The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War II. The artillery fire and its accuracy were observed and directed by artillery air pilots who were flying reconnaissance planes over the battle field. Before the troops gained any shore area to build landing strips, the planes had to be based at sea. The large air carriers could not approach the shores close enough. Dr. Raines writes, "At the very opening of the ground campaign, Tenth Army introduced a major innovation in air-observation-post operations, at least as far as the U.S. Army was concerned. Selected pilots used a Brodie device to provide observed fire during the landings." A Brodie device was a complex combination of wires, cables, poles, a hook, a trolley, and a trapeze.Originally, for practice purposes, it was built on land. It was meant to send the planes into the air and also to catch those at the end of a mission without having the wheels touch the ground or the deck of an aircraft carrier. Later the Brodie device was mounted on a landing ship tank LST-776, which allowed for a relatively smaller floating vessel to come closer to the shore and "permitted Field Artillery planes to observe fire continuously during a landing. It eliminated the dependence on aircraft carriers to transport light aircraft to the landing area […]."

Brodie device installed and in action on LST 776. 1945. Photo is borrowed from the Internet.

Charles Ernest brought his expertise, skills, and personal courage into the picture. Dr. Raines continues, "The XXIV Corps artillery air officer, Major Charles Ernest, had learned to fly off a land-based Brodie rig […]. He began training selected pilots in its use. […] Ernest and most of his men received the intense training needed to operate such complex gear. When XXIV Corps landed in Okinawa on April 1 1945, the Brodie device and the pilots using it functioned almost flawlessly, making twenty-five takeoffs and landings until engineers could prepare strips ashore."

Charles Ernest operated small reconnaissance planes, probably L-4, also known as Piper Cubs or Grasshoppers. It may have been one of those planes that he and his army fellows flew on November 2, 1945 to land on a forest clearing just north of the 38th Parallel.

After the Second World War, Ernest was stationed in Camp Polk, Louisiana. In July 1952, while at Camp Polk, 45-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ernest received orders assigning him to the Far East again, to Korea. This extraordinary man’s passion was flying. The National Archives hold several photos of Charles Ernest. They are all about flying or teaching others to fly. There, among other duties, he served once again as a pilot instructor, teaching Korean students of the Army Aviation School.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Ernest passed away on January 15, 1965 at the age of 57 and was buried with military honors at the Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, CA.

The note in Russian says, "As a memento from a US Army officer Naum Kreiman to the comrade from the Soviet Union. November 3, 1945" ("На память от офицера армии США Наума Креймана товарищу [из] Советского Союза. 3/XI-45 г.").

Naum Kreiman

Certainly, Naum Kreiman was the one who acted as an interpreter during those two days. His well-established Russian handwriting suggests that he was fluent in Russian. On the Korean bill, he spelled out his name in Russian so clearly, that there was no doubt about it. I did not have to spend hours with the magnifying glass, struggling over each letter. But how did he spell his last name in English? Kraman? Kraiman? Krayman? Crayman? Creyman? Creiman? Did he modify his first name Naum to something else? Online telephone directories readily offer vast numbers of any of the given name; most offers are hidden behind the payment option. A friend of mine, a professional interpreter, suggested yet another spelling, Kreiman. This one added dozens of additional phone numbers to the impressive list I had.

I decided to first concentrate my search on the Eastern shore. A lot of Jewish immigrants traditionally settle down here. Having printed out pages of phone numbers, I started calling. Half of the numbers were wrong or disconnected. Once I thought I caught my luck by the tail. A Russian-speaking woman said that, yes, they had a WWII veteran by this name in the family. Immediately it turned out that he fought on the Soviet side. I needed an American officer.

Time passed by and I was about to give up when I stumbled over a website that promised tools to build a genealogical tree. I registered and started running the names of all those who signed the Korean bill in 1945. What I discovered blew my mind away. A name Naums Kreimanis on the passenger list of a ship leaving Latvia in 1939. An application for relief from military duty, signed by Naum Kreiman in 1942. Cindy Kreiman, old enough to be his daughter and residing in Virginia… I found her most recent address and wrote a note. Two weeks later I got a phone call. A gentle voice at the other end said, "Hi, I am Cindy Kreiman."

Naum Kreiman. 1945. From the family archive.

Naum Kreiman was born on June 2, 1920 to a Russian-speaking Jewish family in Riga, Latvia. By the time WWII broke out, he was a student. To be a Jew in Latvia in 1939, when the Nazis were rising, was quite scary for many. A lot of Jews fled to the West. Naum’s father was certain that nothing would happen to them: they had a small family business that could be beneficial for any regime. Naum’s mother was of a different opinion and insisted that Naum leave the country. So he did. On September 30, 1939, he got on the last trans-Atlantic ship that would go out; nobody could leave Latvia after that.

On October 14, 1939 the ship Kungsholm arrived in New York, NY from Gothenburg, Sweden. A 19-year-old student Naums Kreimanis was on it. On the Passenger List he was Number 13. In his immigration papers Naum stated that he was heading to Washington, D.C. His distant relative, a 70-year-old Nathan Kronman, lived there with his wife Mollie and three daughters. He would help Naum settle in.

Starting with the spring semester of 1940, Naum was studying engineering in Illinois. He did not know much of English, and school was not easy for him. Once there was an incident that his memory would not let go. In one of his classes he hit a language barrier and could not understand something important, so he asked for help. His fellow student brushed him off by saying, "Go back to your country, you […] foreigner." Naum never asked for help again. He learned English perfectly. On top of Latvian, Russian, and English, he knew German, Yiddish, and Latin. Several years later this knowledge of foreign languages would turn out to be a commodity that would greatly determine his fate.

Naum Kreiman knew the value of education. In order to have an uninterrupted course of studies, he applied for relief from the military services. He was an excellent student, and got his degree in record time – in two and a half years.

He did not have fears about going to war. He knew too well what Nazism was about. Back in Latvia things were gloomy and tragic. Naum’s brother was involved in the Jewish Underground. He was shot by the Nazis and died later of lead poisoning from the bullet wounds. His parents vanished. His uncle Abraham Kreiman, who was to be burned in the death camp’s ovens three times, miraculously survived the Holocaust.

Naum Kreiman was ready to join the War effort; he knew all too well the atrocities of fascism and he felt he had a moral obligation to help defeat the Nazis. At 25 years old, in 1945 he got his US citizenship and enlisted in the Army. His military service started on July 7, 1945. His knowledge of languages defined his military profession: he served in the Army Intelligence. He was deployed where the action was still going on, to the Pacific front.

Nuclear shadow similar to what Kreiman witnessed in Nagasaki. Photo is borrowed from the Internet.

On August 6th and 9th, 1945, the world witnessed the first two atomic bombings in Japan. About a week after the second bombing, Naum Kreiman arrived in Nagasaki. The devastation there was beyond comprehension. What stuck in his memory was a remnant of a street pole with a permanent "nuclear shadow," recollect Naum’s daughters Cindy and Simona. Such flash marks were produced on the asphalt by thermal radiation. A crow was sitting on top of the pole.

Amiral C. Nimitz is signing the peace Instrument on board of USS Missouri. September 2, 1945. Photo is borrowed from the Internet.

On September 2nd, to document the surrender of Japan, the representatives of the Allied forces and Japan arrived on board the battleship USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. Lt. Naum Kreiman acted as an interpreter during this historic event. Those who were on that day aboard USS Missouri received a document commemorating it. Naum’s family treasures it to this day. It simply says, "Certifying the presence of Lt. Naum Kreiman at the formal surrender of the Japanese Forces to the Allied Powers." It is a small piece of paper, where the red sun – the flag of the Imperial Japanese Army – is drawn slightly off-center, a powerful visual message of defeat. It was signed by the commanding American officers of the Pacific front: D. MacArthur, S. Murray, C. Nimitz, and W. Halsey, Jr.

Later in the fall of 1945 the war machine brought Naum Kreiman to Korea, next to the 38th Parallel, where he and his friends met the Soviet officer Vladimir Epstein. Here, too, Naum was an interpreter.

Naum Kreiman with Gertrud and her family.

Germany, 1948.

Naum Kreiman was a man of great personal courage and was never afraid of unconventional decisions. After the war was over, Kreiman was stationed in Germany, a country sliced in two by the peace treaty. The following episode shows how bold and daring he could be. Naum’s aunt lived in East Berlin. To bring her to West Berlin was next to impossible. People were finding new and unusual ways to cross the border, but there were a lot of failures and even deaths. Naum decided to smuggle his aunt, a very small woman, in the trunk of his car. At Checkpoint Charlie all the cars were thoroughly inspected. When the truck in front of Naum’s car went through the inspection, and the gate opened to let it through, Naum noticed in his rear view mirror that his own trunk opened. He floored the gas pedal and zipped through the gate risking everything, including his aunt's and his own life.

While still in Germany, Naum Kreiman experienced another very emotional incident, which changed his life forever. Someone he knew was supposed to deliver a letter to a woman named Gertrud, but because he could not make it, he asked Naum to do so. Naum saw Gertrud, and it was love at first sight. In 1948 the two married, and in 1951 Naum brought her home, to the U.S. where their twins Cindy and Simona were born.

The Soviet paper bill with signatures dated by November 3, 1945. The Kreimans' family archives.

After the war, Naum Kreiman was a government employee. The Kreimans resided in Washington, D.C. Naum Kreiman passed away on May 30, 1991 in Boston, MA just three days short of his 71st birthday.

The Kreiman sisters cherish everything that was dear to their father’s heart: his medals, photographs and about half a dozen war-time paper bank notes from different countries. Most of them still have readable notes and signatures of those who eye-witnessed the end of the War. A Philippine one-peso bill has about twenty signatures of the people that Naum met in Japan between August 25th and 31st, 1945. Among those pieces of currency was also a ten-ruble Soviet bill, covered with hand-written text. The first note says, "To a dear fellow-countryman, in memory of this accidental meeting in Korea, from Captain Vladimir Semionovich Epstein. November 3rd, 1945." Below, there are signatures of Private Philippe J. Durette, Major Charles Ernest, and Major John J. Ghingher, Jr.

The circle is complete!

The U.S. veteran Naum Kreiman, just like the Soviet veteran Vladimir Epstein never parted with those simple but meaningful keepsakes, no matter where he lived in the years to come. Those tangible symbols of friendship and peace never faded.

This was meant to be a piece to fill in a gap of the unwritten part of our history, a portrait of a few individual faces of brave men in uniform on the canvas of the Big War. They spoke different tongues, but were united by a common enemy, a common goal, a common Victory.

Vladimir S. Epstein.

Naum S. Kreiman.

John J. Ghingher Jr.

Charles Ernest.

Philippe J. A. Durette.

A tribute to them.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks are extended to:

the Durette, the Ghingher, and the Kreiman families for sharing their personal memories and photographs;

Dr. Edgar F. Raines, the author of "Eyes of Artillery. The Origins of Modern U.S. Army Aviation in World War I" for his kind consultation;

Mr. Rich Boylan, a historian and a consultant at the National Archives, College Park, MD, for his extensive professional knowledge and outstanding effort to help;

Celia Anklesaria and Darya Soldatenkov for their time and effort in helping the authors with the search.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

20:43 22.03.2015 •

20:43 22.03.2015 •