The impressive victory scored in last spring’s parliamentary elections in India by Prime Minister Narendra Modi inspired numerous comments about the start of a new stage in the development of one of the largest countries around. However, the spate of dramatic events that have since happened in India has drawn attention to the negative trends in the world’s second most populous nation.

Since its coming to power in May 2014, the current Indian leadership has set itself ambitious and long-term goals aimed at strengthening both the country's authority in the world, its status as a “serious global player” and creating new opportunities for its accelerated development and economic growth.

“Over the past five years, Modi has sought to regain India’s lost strategic position in South Asia and ensure its recognition as a regional leader according to the country's de facto role in the region,” said Dattesh Parulekar, vice president of the Forum for Integrated National Security (FINS). In its effort to overcome the growing imbalances in development, the Modi government launched a number of large-scale economic administrative, financial and social reforms. Moreover, authorities still declare their intention to bring the national GDP to $5 trillion by 2024. [i]

Another important goal being pursued by the government is centralization of the state and national consolidation, which it considers vital for the country’s further development and sway, including in international affairs. From the standpoint of domestic policies, it is primarily about encouraging the growth of Hindu national and religious identity. Hence, as many foreign observers believe, the elimination by the Modi government in August 2018 of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, then the country’s only predominantly Muslim administrative unit. The decision was fully in line with the ultimate goal pursued by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the forces supporting it, i.e. the proclamation of India as a Hindu nation. Playing to the sense of ethnic identity of most of the country's inhabitants already brings political dividends with the BJP winning 37 percent of votes in the last parliamentary elections, compared with 31 percent it had in the previous legislature. Narendra Modi’s party has also been quickly strengthening its hand in state power structures, including through “defections” from rival parties.

On the other hand, the government’s policy of centralization, above all consolidation of the state and society, is inevitably contributing to the radicalization of the country’s ethnic minorities, primarily Muslims, whose number, according to recent estimates, now exceeds 200 million. Last year saw a spate of Muslim protests. In the summer of 2019, the BJP-led government of the northeastern state of Assam established, under the pretext of combating illegal immigration, a National Register of Citizens. Of the state’s 32 million residents, 2 million, mainly Muslims, were recognized as “non-citizens.” In August 2019, the central government revoked the status of limited autonomy granted to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, with local media reports putting the number of protesters under lockdown at “thousands.” [ii]

Finally, a new version of the Indian Citizenship Act, which critics accused of discriminating against Muslims and of being an attempt to undermine the secular underpinnings of the Indian state, was adopted in December, 2019. The new-look Act raised a new wave of protests among the country’s Muslims. As a result, the ethno-religious issue can also become a convenient tool in the hands of Narendra Modi’s opponents.

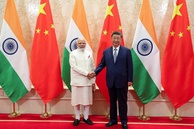

Finally, with the government boosting the country’s national self-awareness, it becomes almost inevitable that it will take a tougher stand vis-à-vis India’s traditional opponent, Pakistan, and its strong economic competitor, China. The escalation of military tensions with Pakistan that happened in February 2019, showed how quickly these two traditional foes can actually come to blows. Moreover, the dispute between Beijing and New Delhi over the ownership of the Aksai Chin Plateau, a region on the border with China, Pakistan and India, indirectly enmeshes Beijing in the territorial problems of Kashmir.

According to Indian observers, “unable to stand up to the inevitable large-scale industrial and infrastructure offensive by China through the Himalayas and the sea routes of South Asia, which are the traditional sphere of India’s influence,” New Delhi needs to implement “a counterbalance strategy.” [iii] However, despite its undoubted foreign policy and diplomatic achievements, which have contributed to Narendra Modi’s popularity inside the country, India has increasingly been lagging behind China in economic terms. Therefore, fundamental financial and economic problems threaten to become India’s Achilles heel.

The relatively slow pace of India’s socio-economic development remains the main obstacle to strengthening the country’s position in Asia and the world as a whole. The country is subject to all the standard “developmental diseases” that always come with accelerated economic and social transformations. The modernization of Indian society is also hampered by vestiges of traditionalism. Intense discussions continue “regarding the sustainability of the current models of socio-economic development.” [iv]

The Economist singles out environmental degradation [v], serious problems in the field of education and a crisis in public administration as the three main challenges to India’s development.

After he came to power in 2014, Narendra Modi had to tackle multiple problems that had remained unsolved for decades. His government is trying to combine federal programs to help the country’s poorest, who account for up to 22 percent of the country's population, with initiatives such as “Make-in-India” and “Startup India” designed to stimulate economic and business development. Experts say that “although no special breakthroughs in these areas have yet occurred, the secret of Modi’s popularity is that he at least started these programs.” [vi]

They also point to the government’s traditional (and growing) appetite for playing a strong directive role in the economy.

In November 2016, the government took out a hefty 86 percent of all cash out of circulation as part of an experiment to root out corruption only to face a liquidity crisis. Combined with a campaign against “shadow economy,” the measure seriously undermined production and employment, slowed down the pace of economic growth, "and also reduced tax revenues." A sweeping reform of the national tax system, undertaken in 2017, provoked a months-long “collapse” of the taxation sphere and sparked mass-scale protests. According to HSBC, India's GDP growth rate has been steadily declining since mid-2017. According to Bloomberg and the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the volume of new investment projects in India has also been declining since 2015. The downturn began a year after Modi came to power. Amid the continuous growth of the Asian countries’ role in the global economy, finance and trade, the current slide of the region’s second largest economy appears very contradictory and illogical.

Narendra Modi and his opponents are fiercely arguing whether the current economic downturn is cyclical or structural. Economists are also debating on this issue. “The government apparently believes the recession is cyclical.” Modi’s critics argue that despite "consistent cuts in interest rates" and a budget deficit "of 102 percent in 2019," the economic slowdown has been going on for several years now, Asia Times wrote. [vii] Mounting problems in the economy even forced New Delhi to withdraw from negotiations on the Comprehensive Regional Economic Partnership (RCEP) after seven years of talks, “literally just a step away from signing the agreement.” According to Indian business publications, RCEP, which was negotiated between ASEAN and the bloc’s six free trade agreement partners, “will now be dominated by China. India’s membership in RCEP would have been tantamount to a trade agreement with China; something Indian industry is unprepared for now.” [viii]

Leading Indian economists believe, however, that pulling out of the RCEP agreement will benefit the Indian economy only if the government “immediately” starts to reform the land, labor and capital markets. New Delhi should also focus on encouraging competition, deregulating the economy and facilitating market access if it doesn’t want to see its regional commodity circulation seriously falling behind China’s, and its capital and technology exports, as well as state financing of domestic companies’ overseas projects, remaining significantly inferior to Chinese.

Russia’s chances of playing an important role in the positive transformation of its long-standing strategic partner look pretty good. In geopolitical terms, we are talking about the dialogue between the leaders of Russia, India and China, which resumed in December 2018. All three parties consistently emphasize the partnership nature of their relations as well as their shared interests and goals “in the field of development.” [ix]

Economy-wise, the Russian Council on Foreign Affairs believes that Moscow can do a lot in terms of helping its Indian partners on issues ranging “from high technology and defense, to building modern infrastructure and poverty reduction.” This, however, requires a qualitative improvement in the existing model of interaction to bring it fully in line with the realities of 21st century global politics, all the more so amid attempts being made by a number of countries, primarily the US, France and Israel, to sidestep Russia on the Indian track.

Right now, it looks like India could be one of the first major world powers to solve a super-complex dilemma of successfully dovetailing the priorities of security and national development. Despite all the shortfalls of his first term in office, Narendra Modi and his team have managed to even expand their support base among voters from across the country’s political spectrum. The government now has to prove its ability to kick start the country's long-term internal development, while simultaneously move toward making India a system forming power in South Asia.

The views of the author may not necessarily reflect the position of the Editorial Board.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

[i] In 2019, the IMF estimated India’s nominal GDP at $3.113 trillion.

[ii] https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/09/detained-in-kashmir/

[v] According to The Economist, 12 out of the world’s 15 “most polluted” cities were in India (autumn 2019).

[vi] https://carnegie.ru/commentary/79204

[vii] https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2797440.html

[ix] http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/59278

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:17 14.01.2020 •

10:17 14.01.2020 •