Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron and Jean-Luc Melenchon.

Pic.: ‘The Article’

According to Article 12 of the French Constitution, "a new dissolution cannot be carried out in the year following these elections"…

Could France be led by a coalition government, minority government or technical government? In the absence of a clear absolute majority in the Assemblée Nationale, there is a risk of deadlock, ‘Le Mond’ writes.

Who will govern France? That's the burning question on everyone's lips after the surprise second round of France's snap parliamentary elections, in which the left-wing Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP) alliance came out on top, albeit far from having an absolute majority in the Assemblée Nationale, which would enable it to claim power uncontested. What are the next steps expected in the wake of the elections? Could the country be heading for deadlock? Here are some key elements to answering these questions.

1. When does a new government have to be appointed?

Prime Minister Gabriel Attal stepped down on Monday, July 8, following the loss of a majority of seats in the Assemblée Nationale. "The fact that a government resigns after legislative elections is a convention," noted Benjamin Morel, a public law lecturer at the Paris-Panthéon-Assas University. However, President Emmanuel Macron has asked Attal stay on as prime minister "for the moment". With less than three weeks to go before the Paris 2024 Olympic Games, and no immediate clear-cut successor, Attal had already said on Sunday he was prepared to remain in the premiership "as long as duty requires" – in other words, until that successor is found.

There is, therefore, no formal timetable that requires Macron to either ask the current government to resign or appoint a new one. The president announced on Sunday that he preferred to "wait for the new Assemblée Nationale to be structured before taking the necessary decisions," in accordance "with the republican tradition."

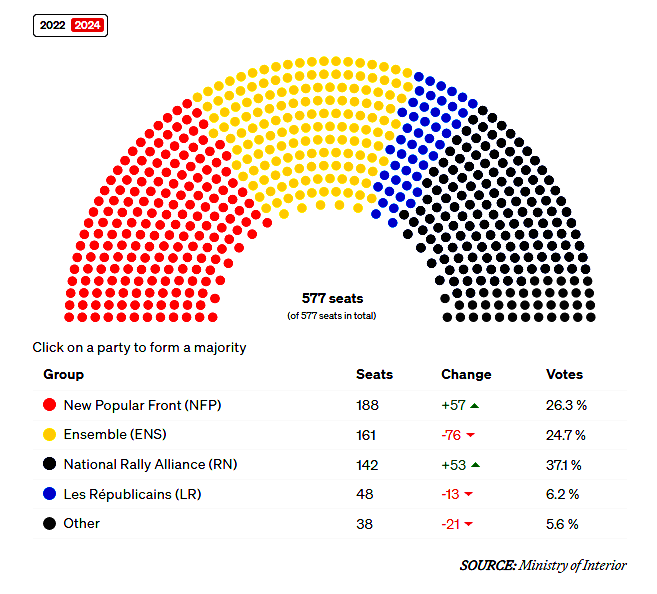

Nevertheless, Macron cannot completely ignore the new political landscape that has emerged as a result of the elections. A government based on the support of a minority in the Assemblée Nationale faces the threat of a motion of no confidence, which could be introduced as early as the first session of the new Assemblée Nationale – scheduled for July 18, as per Article 12 of the French Constitution. This motion of no confidence would have a good chance of being passed, since the presidential coalition now has only 168 seats out of 577, and it would lead to the immediate dismissal of the Attal government.

2. How is the French prime minister chosen?

Theoretically, the president has the power to appoint whomever he wishes to Matignon, the office of the prime minister. However, he cannot override the opinion of the majority of members of the Assemblée, because a government running counter to the chamber's will could be subjected to a motion of no confidence. He is therefore expected to choose a candidate likely to receive the support of a majority – or, at least, one unlikely to be rejected by a majority.

When a political bloc obtains an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections (at least 289, out of the 577 seats in the Assemblée), the situation is simple: A prime minister drawn from its ranks must be appointed, even if they hail from a party that is opposed to the president, as was the case during the "cohabitations" under former presidents François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac.

However, after this year's election, no political group can claim such dominance. The leading bloc, the Nouveau Front Populaire (NFP), has just 182 seats, to which could be added some 13 left-wing independent MPs, giving it a relative majority representing barely a third of the seats in the Assemblée.

3. What are the possible scenarios?

In the absence of a clear majority in the Assemblée Nationale, there is a real risk of institutional deadlock. France's Constitution does not impose any timetable for forming a government, but no legislative or regulatory text can be adopted without one. The negotiations that will take place over the next few days may, or may not, lead to the emergence of one of these situations:

a) A coalition government

Seeing as none of the major political blocs emerged from the parliamentary elections with a majority, discussions could be held to form a coalition capable of gathering more than 50% of the Assemblée's members behind a given prime minister and a governing agreement. This is what happens in some of France's neighbors, such as in Germany and Italy. It was also the idea floated by some political leaders before the second round of the elections, when they spoke of a "government of national unity" or a "provisional government."

For the time being, however, the deal seems to be off to a bad start. The main representatives of the left have already ruled out any prospect of an alliance with Macron's bloc and/or the right, refusing any "alliance of opposites" or any "arrangement." While Macron has yet to speak himself, the leader of his Renaissance party, Stéphane Séjourné, has warned that the presidential coalition will present "preconditions for any discussion" aimed at forging a majority. Macron's supporters have already ruled out any alliance with La France Insoumise (LFI, radical left), which has retained its position as the leading component of the left-wing bloc, with 74 MPs. Former prime minister and head of the Horizons (center-right, Macron- allied) party Edouard Philippe has also said he wants to "favor the creation of an agreement" excluding the Rassemblement National (RN, far-right) or LFI. Meanwhile, Laurent Wauquiez, one of the strongmen of the Les Républicains (LR, right) party, ruled out taking part in "negotiations, combinations, to put together unnatural majorities" backed by the 60 LR and right-wing independent elected members.

b) A minority government

A government could also be appointed and maintained without the explicit support of an absolute majority of MPs in the Assemblée. This was the case with the recent governments of prime ministers Elisabeth Borne and Attal. From 2022 to 2024, they were only backed a relative majority of 246 seats out of 577 (43%) in the Assemblée. The presidential coalition succeeded in keeping these minority governments alive for two years, as opposition parties on the right, left and far right never joined forces to topple them. The Macron-aligned governments had to secure majorities on a case-by-case basis to pass bills, and regularly resorted to using Article 49.3 of the French Consitution to force legislation through without a vote – they survived the ensuing votes of no confidence.

Such a scenario could theoretically allow the Nouveau Front Populaire to govern, but it requires that at least 94 MPs who were not elected under the left-wing alliance's banner would agree to offer it their tacit support. The presidential bloc could also stay in power, provided it could convince 121 MPs from the right or center-left to let it govern. By contrast, given their results, LR and RN have very little chance of securing the premiership in this way.

One thing is certain: In the absence of a clear, stable majority, a minority government would be faced with the constant threat of a vote of no confidence in the Assemblée Nationale, which could lead to several governments replacing each other in quick succession.

c) A 'technocratic' government

If the situation became deadlocked, the appointment of a "technocratic" government could come to be seen as a way out. This would involve appointing ministers with no party affiliation to manage day-to-day matters and implement certain reforms on a consensus basis, with the support of various blocs in the Assemblée on a case-by-case basis.

This is a configuration that Italy has experienced on several occasions, in times of crisis, but which has never lasted very long. Indeed, it is difficult for such a government to sustain itself over the long term, in the absence of electoral legitimacy.

4. Could there be new elections soon?

No. According to Article 12 of the French Constitution, "a new dissolution cannot be carried out in the year following these elections." The new Assemblée Nationale should, therefore, remain in office until at least the summer of 2025.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:35 12.07.2024 •

11:35 12.07.2024 •