This is a stunning ‘The New York Times’ investigation that details - on two dozen pages - how the Pentagon is participating in the war against Russia in Ukraine. The article directly states that US Army officers are guiding American missiles that attack Russian territory. American officers are planning military operations of the Ukrainian army against Russia. Such candid material demonstrates that the US is in a state of war with Russia. This is the legacy Biden left to Trump. Now it's up to Trump - does he want an escalation of the war against Russia? This cannot go on forever!

Below are the most important details that are revealed in this article.

Photo: NYT

Photo: NYT

With remarkable transparency, the Pentagon has offered a public inventory of the $66.5 billion array of weaponry supplied to Ukraine — including, at last count, more than a half-billion rounds of small-arms ammunition and grenades, 10,000 Javelin antiarmor weapons, 3,000 Stinger antiaircraft systems, 272 howitzers, 76 tanks, 40 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, 20 Mi-17 helicopters and three Patriot air defense batteries.

But a New York Times investigation reveals that America was woven into the war far more intimately and broadly than previously understood.

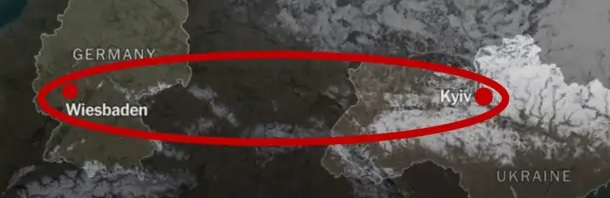

Side by side in Wiesbaden’s mission command center, American and Ukrainian officers planned Kyiv’s counteroffensives. A vast American intelligence-collection effort both guided big-picture battle strategy and funneled precise targeting information down to Ukrainian soldiers in the field.

One European intelligence chief recalled being taken aback to learn how deeply enmeshed his N.A.T.O. counterparts had become in Ukrainian operations. “They are part of the kill chain now,” he said.

In mid-2022, using American intelligence and targeting information, the Ukrainians unleashed a rocket barrage at the headquarters of the 58th in the Kherson region, killing generals and staff officers inside. Again and again, the group set up at another location; each time, the Americans found it and the Ukrainians destroyed it.

Farther south, the partners set their sights on the Crimean port of Sevastopol.

At the height of Ukraine’s 2022 counteroffensive, a predawn swarm of maritime drones, with support from the Central Intelligence Agency, attacked the port, damaging several warships and prompting the Russians to begin pulling them back.

The partnership operated in the shadow of deepest geopolitical fear — that Mr. Putin might see it as breaching a red line of military engagement and make good on his often-brandished nuclear threats. The story of the partnership shows how close the Americans and their allies sometimes came to that red line, how increasingly dire events forced them — some said too slowly — to advance it to more perilous ground and how they carefully devised protocols to remain on the safe side of it.

Time and again, the Biden administration authorized clandestine operations it had previously prohibited. American military advisers were dispatched to Kyiv and later allowed to travel closer to the fighting. Military and C.I.A. officers in Wiesbaden helped plan and support a campaign of Ukrainian strikes in Russian-annexed Crimea. Finally, the military and then the C.I.A. received the green light to enable pinpoint strikes deep inside Russia itself.

In some ways, Ukraine was, on a wider canvas, a rematch in a long history of U.S.-Russia proxy wars — Vietnam in the 1960s, Afghanistan in the 1980s, Syria three decades later.

During the wars against the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan and against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, American forces conducted their own ground operations and supported those of their local partners. In Ukraine, by contrast, the U.S. military wasn’t allowed to deploy any of its own soldiers on the battlefield and would have to help remotely.

Unless the coalition reoriented its own ambitions, General Donahue and the commander of U.S. Army Europe and Africa, Gen. Christopher G. Cavoli, concluded, the hopelessly outmanned and outgunned Ukrainians would lose the war. The coalition, in other words, would have to start providing heavy offensive weapons — M777 artillery batteries and shells.

A Polish general became General Donahue’s deputy. A British general would manage the logistics hub. A Canadian would oversee training.

The Biden administration had previously arranged emergency shipments of antiaircraft and antitank weapons. The M777s were something else entirely — the first big leap into supporting a major ground war.

The defense secretary, Lloyd J. Austin III, and General Milley had put the 18th Airborne in charge of delivering weapons and advising the Ukrainians on how to use them.

The auditorium basement became what is known as a fusion center, producing intelligence about Russian battlefield positions, movements and intentions. There, according to intelligence officials, officers from the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency were joined by coalition intelligence officers.

At an international conference on April 26 at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, General Milley introduced Mr. Reznikov (defence minister) and Zaluzhny (commander in-chief) deputy to Generals Cavoli and Donahue. “These are your guys right here,” General Milley told them, adding: “You’ve got to work with them. They’re going to help you.”

Bonds of trust were being forged. Mr. Reznikov agreed to talk to General Zaluzhny. Back in Kyiv, “we organized the composition of a delegation” to Wiesbaden, Mr. Reznikov said. “And so it began.”

Soon the Ukrainians, nearly 20 in all — intelligence officers, operational planners, communications and fire-control specialists — began arriving in Wiesbaden. Every morning, officers recalled, the Ukrainians and Americans gathered to survey Russian weapons systems and ground forces and determine the ripest, highest-value targets. The priority lists were then handed over to the intelligence fusion center, where officers analyzed streams of data to pinpoint the targets’ locations.

Inside the U.S. European Command, this process gave rise to a fine but fraught linguistic debate: Given the delicacy of the mission, was it unduly provocative to call targets “targets”?

The debate was settled by Maj. Gen. Timothy D. Brown, European Command’s intelligence chief: The locations of Russian forces would be “points of interest.” Intelligence on airborne threats would be “tracks of interest.”

“If you ever get asked the question, ‘Did you pass a target to the Ukrainians?’ you can legitimately not be lying when you say, ‘No, I did not,’” one U.S. official explained.

Each point of interest would have to adhere to intelligence-sharing rules crafted to blunt the risk of Russian retaliation against N.A.T.O. partners.

To give the Ukrainians compensatory advantages of precision, speed and range, Generals Cavoli and Donahue soon proposed a far bigger leap — providing High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, known as HIMARS, which used satellite-guided rockets to execute strikes up to 50 miles away.

When the generals requested HIMARS, one official recalled, the moment felt like “standing on that line, wondering, if you take a step forward, is World War III going to break out?”

And when the White House took that step forward, the official said, Task Force Dragon was becoming “the entire back office of the war.”

Wiesbaden would oversee each HIMARS strike. General Donahue and his aides would review the Ukrainians’ target lists and advise them on positioning their launchers and timing their strikes. The Ukrainians were supposed to only use coordinates the Americans provided. To fire a warhead, HIMARS operators needed a special electronic key card, which the Americans could deactivate anytime.

HIMARS strikes that resulted in 100 or more Russian dead or wounded came almost weekly.

Together the partners were honing a killing machine.

The Biden administration had authorized helping the Ukrainians develop, manufacture and deploy a nascent fleet of maritime drones to attack Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. (The Americans gave the Ukrainians an early prototype meant to counter a Chinese naval assault on Taiwan.) First, the Navy was allowed to share points of interest for Russian warships just beyond Crimea’s territorial waters. In October, with leeway to act within Crimea itself, the C.I.A. covertly started supporting drone strikes on the port of Sevastopol.

The Ukrainian draft age was 27. General Cavoli, who had been promoted to supreme allied commander for Europe, implored General Zaluzhny to “get your 18-year-olds in the game.” But the Americans concluded that neither the president nor the general would own such a politically fraught decision.

So Generals Cavoli and Aguto recommended the next quantum leap, giving the Ukrainians Army Tactical Missile Systems — missiles, known as ATACMS, that can travel up to 190 miles — to make it harder for Russian forces in Crimea to help defend Melitopol.

Some months earlier, General Aguto had been allowed to send a small team, about a dozen officers, to Kyiv, easing the prohibition on American boots on Ukrainian ground. So as not to evoke memories of the American military advisers sent to South Vietnam in the slide to full-scale war, they would be known as “subject matter experts.” Then, after the Ukrainian leadership shake-up, to build confidence and coordination, the administration more than tripled the number of officers in Kyiv, to about three dozen; they could now plainly be called advisers, though they would still be confined to the Kyiv area.

Perhaps the hardest red line, though, was the Russian border. Soon that line, too, would be redrawn.

In April, the financing logjam was finally cleared, and 180 more ATACMS, dozens of armored vehicles and 85,000 155-millimeter shells started flowing in from Poland.

Generals Cavoli and Aguto were tasked with creating an “ops box” — a zone on Russian soil in which the Ukrainians could fire U.S.-supplied weapons and Wiesbaden could support their strikes.

At first they advocated an expansive box, to encompass a concomitant threat: the glide bombs — crude Soviet-era bombs transformed into precision weapons with wings and fins — that were raining terror on Kharkiv. A box extending about 190 miles would let the Ukrainians use their new ATACMS to hit glide-bomb fields and other targets deep inside Russia.

The generals were instructed to draw up two options — one extending about 50 miles into Russia, standard HIMARS range, and one nearly twice as deep.

The C.I.A. was also authorized to send officers to the Kharkiv region to assist their Ukrainian counterparts with operations inside the box.

The box went live at the end of May.

In August in Wiesbaden, General Aguto’s tour was coming to its scheduled end. He left on the 9th. The same day, the Ukrainians dropped a cryptic reference to something happening in the north.

On Aug. 10, the C.I.A. station chief left, too, for a job at headquarters. In the churn of command, General Syrsky made his move — sending troops across the southwest Russian border, into the region of Kursk.

For the Americans, the incursion’s unfolding was a significant breach of trust. It wasn’t just that the Ukrainians had again kept them in the dark; they had secretly crossed a mutually agreed-upon line, taking coalition-supplied equipment into Russian territory encompassed by the ops box, in violation of rules laid down when it was created.

“It wasn’t almost blackmail, it was blackmail,” a senior Pentagon official said.

General Aguto had selected the targets for Operation Lunar Hail. The campaign required a degree of hand-holding not seen since General Donahue’s day. American and British officers would oversee virtually every aspect of each strike, from determining the coordinates to calculating the missiles’ flight paths.

Of roughly 100 targets across Crimea, the most coveted was the Kerch Strait Bridge, linking the peninsula to the Russian mainland.

After the partners agreed on Lunar Hail, the White House authorized the military and C.I.A. to secretly work with the Ukrainians and the British on a blueprint of attack to bring the bridge downs.

For the Biden administration, the failed Kerch attack, together with a scarcity of ATACMS, reinforced the importance of helping the Ukrainians use their fleet of long-distance attack drones. The main challenge was evading Russian air defenses and pinpointing targets.

Longstanding policy barred the C.I.A. from providing intelligence on targets on Russian soil. So the administration would let the C.I.A. request “variances,” carve-outs authorizing the spy agency to support strikes inside Russia to achieve specific objectives.

Intelligence had identified a vast munitions depot in the lakeside town of Toropets, some 290 miles north of the Ukrainian border, that was providing weapons to Russian forces in Kharkiv and Kursk. The administration approved the variance. Toropets would be a test of concept.

C.I.A. officers shared intelligence about the depot’s munitions and vulnerabilities, as well as Russian defense systems on the way to Toropets. They calculated how many drones the operation would require and charted their circuitous flight paths.

On Sept. 18, a large swarm of drones slammed into the munitions depot. The blast, as powerful as a small earthquake.

In his last, lame-duck weeks, Mr. Biden made a flurry of moves to stay the course, at least for the moment, and shore up his Ukraine project.

He crossed his final red line — expanding the ops box to allow ATACMS and British Storm Shadow strikes into Russia.

The administration also authorized Wiesbaden and the C.I.A. to support long-range missile and drone strikes into a section of southern Russia used as a staging area for the assault on Pokrovsk, and allowed the military advisers to leave Kyiv for command posts closer to the fighting.

In December 2024, General Donahue got his fourth star and returned to Wiesbaden as commander of U.S. Army Europe and Africa.

In early January 2025, Generals Donahue and Cavoli visited Kyiv to meet with General Syrsky and ensure that he agreed on plans to replenish Ukrainian brigades and shore up their lines, the Pentagon official said. From there, they traveled to Ramstein Air Base, where they met Mr. Austin for what would be the final gathering of coalition defense chiefs before everything changed.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:16 03.04.2025 •

10:16 03.04.2025 •