Dear Geoff,

It was a genuine pleasure to read your Zona. Indeed, The Stalker disturbs, as do Christian truths. It may come as a shock therapy in that it makes people think of Life Questions. The reflection can produce different outcomes, none of them absolute or comprehensive. Since you invite comments, I dare share with you some ideas that hopefully will address some of the loose ends of your narrative. Your essay is primarily about the impression Andrei Tarkovsky’s film makes. So, I’ll try to keep to that ground which allows maximum freedom. I will not distinguish between what is subjective or objective, conscious or subconscious or just formative in respect of the film and its director’s design.

* * *

You on purpose leave religious beliefs outside your analysis. But those seem to be absolutely central to the very plot of the Stalker. The Mirror and, particularly, Andrei Roublyov (originally named Andrei Passion) provide enough grounds for such an approach. To a person, who if not religious, but at least is conscious of those issues, the Zona may constitute an incarnation of living omnipresent God, who relates to human existence through what is supposed to be conscience or moral law.

Such a view would be premised upon continuity of the Russian literary tradition, of which A.Tarkovsky’s works were part and parcel. Our literature of the XIX-th century, though to a great extent a product of the modernization drive, launched by Peter the Great had Christianity as a source of inspiration. In that sense we took up the torch that was slipping off the Western hands.

Of importance in that regard is Oswald Spengler’s analysis in his Decline of Europe. It is a culturological treatise that, too, shuns topics of religion and morals. He tried to compile cultural evidence to support Germany’s claim to leadership of the West. That was a wishful thinking. He would live long enough to see why: the Nazi experiment would make him sever ties with the Nietzcshe foundation. But his method proves to be a very fruitful one. It reveals, from within, the cultural roots of what happened to the West, starting with the French Revolution and especially in the XX-th century and is still happening now (Brad Gregory in his Unintended Reformation traces the origins much deeper in history).

Oswald Spengler makes a distinction between culture and civilization, the former a living thing, capable of development, the latter static, having lost that potential. There are other views on the difference between the twain. For example, Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev gives this definition to culture: “Culture means processing material with an act of spirit, a victory of form over matter”.

According to O. Spengler, Baroque was the last great style of the Western culture, including music. Beyond that it lost its residual source of inspiration, and thus couldn’t be a reflection of something that had ceased to be, i.e. harmony in the human soul, the latter being une chretienne (sorry, the English doesn’t have a gender for it, but both in the Russian and French it is feminine). It may impart some additional meaning to the famous phrase of Taleyrand: “The one who didn’t live in the XVIII-th century, hasn’t lived at all.” (The exact quote is: «Qui n’a pas vécu dans les années voisines de 1789, ne sait pas ce que c’est que la douceur de vivre ». (“Those who have not lived through the years around 1789 cannot know what is meant by the pleasure of life.”).

Ivan Tourgenev missed a lot this last creative gasp of the European culture, as noted Leonid Grossman (a leading literary critic of the first half of the XX-th century). For him, it was the purist expression of ever-victorious power of beauty which rules the world. He wrote that “Venus of Milos is more unquestionable than Roman law and principles of 1789.” (By the way, my daughter’s classmates - eleven-year olds of multicultural background - could appreciate the beauty of P.Tchaikovsky’s Autumn Song, which sort of raised her rating in the band.) The nostalgia for the XVIII-th century art (the Wallace Collection?) was symbolized for him in a portrait of a woman, that he called Manon Lescault (he even translated the novel into Russian). Maybe, that could be explained by the fact that it rendered what was left of the lost harmony of human existence. And it may well be that Bethoven’s music, as much as pianoforte, timely and forcefully marked the start of a new world. By the way, Mumu’s author, always depressed by thoughts of his nation’s future, at the end of his life came to believe that it was impossible for death to prevail where creative values of highest order had shone.

Our turn-of-the century philosopher and poet Vladimir Solovyov made this distinction between a life that happens to be and a life that ought to be, between the crude force of the existing and the spiritual faith in the truth and good. Like O.Spengler, he told civilization from culture. In his view, people of the fact live other people’s life, but life is created by people of faith. For him, F.Dostoyevsky was the first author to preach a life that ought to be.

The powerful image of Malena (Monica Bellucci), when she returns to her town with her husband, proves this point: no dirt, she had had to go through, did stick to her. Her humanity and beauty prevail over a life that happens to be. Prince Myshkin says to Nastassya Filippovna: “you have emerged pure from such a hell”.

F.Dostoyevsky, in fact, shared that view of static Europe as “dear stones”. Material culture inspired by Christianity, of which we didn’t have much, probably was what he meant by our European nostalgia. Indeed, one of the flaws of Russian life was lack of shape/form, it was too fluid. That’s why even dandyism of the late XVIII - early XIX centuries (George Brammel, Scarlet Pimpernel etc.) was a welcome trend in Russia’s cultural life. After all, it somehow shaped our existence, given “general gaseousness of Russia” (Ivan Tourgenev). Pushkin, Griboyedov, Chaadayev, Lermontov, all great names of our literature of the time paid homage to that cultural trend. In literature, those were Onegin and Pechorin. For them it was, first of all, about elegant manners. But that may also be viewed as an attempt to prolong the dying XVIII-th century, the loss European society wouldn’t be able to get over for more than a century.

It is difficult to deny that this phenomenon of European spirit had a lot to do with human dignity. It is still the form, including your great tradition to dress for dinner, that makes a stronger part of Britain today. It was a losing battle of the form that had lost substance and became an empty shell. So, D.H.Lawrence was, perhaps, right to change the topic, trying to make sense of life where it belonged beyond reasonable doubt.

The Silver Age of Russian poetry was also an homage to the trend. But beyond that, as Alexander Blok and Anna Akhmatova prove, it helped preserve not only the precious little thing of culture, but also great spiritual values.

The trend in the life of Soviet youth in late 50-ies to early 60-ies, which got the name of stilyagi (it coincided with Nikita Khrushchev’s Thaw), makes the same point. It represented a protest against the life that happened at the time. Maybe, you’ll be interested to watch a recent film Stilyagi, which renders that phenomenon of young people wearing drainpipe trousers and kipper ties and dancing to American tunes, and being persecuted for that. It also leads one to conclude that The Beatles did more to inspire change in the Soviet Union, than the US with their arms race or the Saudis with their bringing the world price of oil down to the rock bottom. That was the time of the British soft power at its highest point, when Britain needn’t take part in foreign wars to claim international influence and relevance, for it was about culture, which passes genuine judgements of history and defines nations’ destinies.

It is ultimate in the arts, when form equals substance. Like poetry, with its rhyme and music, it provides a convincing testimony to the truth. Thus, style equals beauty, which, in its turn, equals the truth. To follow up, does a search for the truth equal a search for beauty? How does feeling beauty relate to knowledge of the truth? If the sense of style of the establishment did, indeed, save Britain from fascist temptations, then it proves precisely that. Like W.Churchill’s instincts and strength of character, which seemed suspect to many at the time, proved to be the right phsychological and emotional framework for the nation’s response to the challenge of Nazi Germany.

Gustave Flaubert dreamed of writing a novel representing nothing, but style. It is appropriate to mention that such a novel had been written by then. It was Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls. It constituted the greatest misunderstanding in the whole of our literature. The critics of the time, and in fact everybody, thought it to be a satire (and even convinced the author of that), although it was neither realistic nor fantastic. And only Vassily Rozanov saw in it both the truth and the unique creative method (Vladimir Nabokov came close to that opinion in his lecture on Gogol, singling him out in Russian literature as the purest expression of creativity/imagination, a pure flight of inspiration). To him it exposed, through its style, a rotten style in the Russian life, which was easy to destroy when the time came for Alexander II’s Great Reforms. By its enormity, this phenomenon in literature can only compare to the mystification represented by the W.Shakespeare authorship question.

Maybe, that is why one feels like watching, time and again, the films, that are about style as substance, like The Scarlet Pimpernel (without prejudice to the cause), The Bondiana (with a less convincing, ideological cause), The Pride and Prejudice etc.? They follow the trend of the pure style, set by The Mother Goose rhymes. Kate Winslet in The Reader is quite convincing in how literature, including A Lady with a Lapdog, accomplishes an individual’s ascension to humanity, which assumes, among other things, repentance and redemption.

The contradiction between cultural and spiritual aspirations of human soul and the crude life on the ground, a reality aggravated by the Industrial Revolution, might have contributed to the ultimate denouement of the XX-th century, starting with the First World War. Like Percy Blackney’s double cravate couldn’t trump la Grande Terreur, this enormous secondary simplification (according to Konstantin Leontyev) of European society couldn’t reintroduce the lost harmony into European life. Perhaps, that is why the obsession with, sort of insistence on, contemporary/modern art, maybe, as a way to delude oneself, to prove that harmony is, after all, not lost forever.

Karl Jaspers acknowledged the human averaging as a real problem of European society and history. In Russia, we resisted the averaging of personality and human soul, which seems to be a fundamental product of civilization, making people more predictable and, thus less interesting and less creative. This narrows the range of the ways in which individuals express themselves, which may be good since it eliminates extreme low points of human behavior, but at the price of making highest points unattainable either. Certainly, in all of our history we suffered from this inability to go average. Still, that made us capable of destroying the Nazi Germany’s war machine, when there was nobody else to do the job (Russia’s treatment by Europe in the last two centuries reminds me of R. Kipling’s Tommy).

Life, hopefully, is not about living average lives, but utterly individual ones. Certainly, we wouldn’t have been less human, had there been no revelations like Shakespeare or Dostoyevsky. But our humanity, frail at all times, would have been less obvious, which would have made a big difference at a critical junctures of history. Nikolai Berdyaev wrote that “Dostoyevsky is the greatest value which the Russian people will justify its existence in the world with, which it will point to at the Judgement of nations”.

* * *

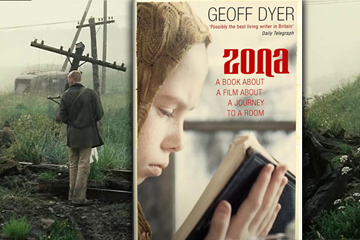

The choice of a love poem by Fyodor Tyutchev passed without your comment (though, perhaps, intuitively this was by far compensated for by bringing the image of the girl reading it to the book’s cover, its implicit poignancy well appreciated). This is one of the translations of this poem, one of very few by its intimacy in our literature:

Dear one, I love thine eyes, amazed

By their quick play and brilliancy;

When of a sudden they are raised,

It is as if the whole wide sky

With heavenly lightning burned and blazed.

But stronger magic doth inspire

Those eyes when suddenly cast down

In fevered moments of desire;

And through the drooping lids ‘tis shown

Passion has lit her smouldering fire.

(Translated by Maud F. Jerrold)

Fyodor Tyutchev was not only a great poet, but also a philosopher and political thinker. The depth of his philosophical poetry was appreciated by Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy. To a great extent he was Dostoyevsky’s predecessor. It was not by chance that in his Pushkin speech (June, 1880) Dostoyevsky cites Tyutchev’s poem These poor villages to support his idea of the Russian people’s panhumanity. Those lines read as follows (in word-for-word translation): “Burdened with the weight of the Cross/All of you, my native country,/In a slave’s image the heavenly Tsar,/Have walked the length and breadth of, while blessing you.” The point he was making was why, given that, “Russia cannot embrace His word, for it is not about the glory of sword and science, but fraternity of people, panhuman cohesion”, the proof of which he saw in universal responsiveness of Pushkin’s works (especially in his Little Tragedies, all of them on European themes, with The Feast at the Time of Plague, a scene from English history, among his most powerful verse). Thus, it was not in terms of power and control that he defined Russia’s mission in history. By the way, this culture-based argument is increasingly coming to the fore of the present-day intellectual and political discourse. Georgy Adamovich (our leading émigré literary critic) wrote: “Russia, made wise by her experience, has learnt many things, that the West has never known at all”.

It is worth mentioning that F.Tyutchev (in his unfinished treatise Russia and the West) saw a fateful flaw of the Reformation in the Protestants’ making themselves judges in their own case, starting along the road leading to a man-God and ultimately to F.Nietzsche. Francis Fukuyama in a recent article (IHT, 4 May 2010) wrote that the Western political thought has not, till now, overcome this denial of equality of human dignity, the core idea of Christianity. It was a terrible implication of F.Nietzsche’s notion of the death of God. Whatever the sins of the Church of Rome, her Indulgences were replaced with a single blanket indulgence, written out by men to themselves. It also meant collectivization of individual responsibility. The burden of Christian freedom as an imperative to choose between good and evil has, thus, been shared. So, the Bolsheviks were not the first to embark on this slippery road.

In his Notes from the Underground (they preceded his great novels, starting with The Crime and Punishment) Fyodor Dostoyevsky explores the issue of what the person of the era of religious consciousness’ crisis is like. So, it is still about our time. The crux of the matter, to him, is that a person “wishes to live by his own stupid will”, even against his self-interest, enlightened or not. And the space of human freedom is defined as a gap between his will and the flat fact of two-by-two-makes-four. Is the latter determinism the true source of the unbearable lightness of being? Is it also about something that makes economics not an exact science?

The idea of progress and human rights became a surrogate for what had been lost in the European translation of the New Testament, which was pushed aside like another fairy-tale. There is another notion I would like to cite: nothing is more human than anticipation of miracle (to me, it is perfectly rendered in The Nativity, at Night by Geertgen Tot Sint Jans). The trick of money begetting money, though fascinating, seems to be a poor substitute. Overall, some mystery seems to be an essential part of human nature and existence.

It is, indeed, the sense of weakness, rather than strength, which explains part of that difference. Weakness is very human and strength superhuman. Chekhov is almost entirely about human weakness. He is indulgent towards people and doesn’t demand much of them. To me, one of his best stories is Rotschild’s violin: it goes infinitely far in understanding life’s truth. In his Dead Souls N.Gogol wrote: “Everything may happen to man.”

It is not about an external coup, quite often a violent one. It is, as said in the Bible: “Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God» (Jonh 3:3). “Before asking a question “what to do?” one has to heal himself,” wrote V.Solovyov. What is the point of a crowd of blind, deaf, physically handicapped, possessed people asking “what to do?” Sorry, said in 1882, it is politically incorrect today, but it is figurative. The first step towards salvation is to feel one’s weakness and lack of freedom. And according to him and F.Dostoyevsky, an integral part of the Russian nature was consciousness of our sinfulness. Here, too, drawing conclusions from Nazi experience, Karl Jaspers agreed, when wrote that genuine freedom can only be a function of a changed man. The belief that salvation can be achieved without repentance and redemption, is, probably, the greatest European illusion, which the West had in common with the Soviet Union. It is no wonder, that D.H.Lawrence created an image of a perfect sacrificial lamb in his England, my England, meaning that there was something, after all, that was to be redeemed through WWI. The Great War was, among other things, a function of the plain thing of projecting colonial attitudes of the previous era on to the European turf. This process started at the time of the Crimean War and is, probably, continuing now under the guise of a debate on comparative productivity of nations within the European Union.

The mystery, lack of clarity (and clarity smacks of finitude) leaves room for doubt/selfdoubt and faith, but also freedom as opposed to any determinism. This idea is rendered by the words of the Bible: “…For now we see through the glass, darkly” (I Corinthians, 13:12). You remember Nastassya Filippovna in The Idiot, when she meets Prince Myshkin for the first time and says that she had vaguely seen him somewhere before. So, doubt and uncertainty are compatible with faith. More than that, they define the space of human freedom. Otherwise, there wouldn’t have been a choice to make.

Maybe, the ultimate test of any claim to the truth is whether it strikes a chord with the mystery of our nature that we carry within us. Short of that, life becomes lonely and barren. Barren (you used this word once) is a favorite word of D.H.Lawrence, when he speaks of antithesis of life. It is also something that makes personalities flat, when whatever you see is all to it. That lack of depth and inner freedom is in stark contrast with, for example, the main character of Ivan Bunin’s Ash Monday. This loneliness is felt in Albert Camus’ Premier Homme, which, for some, represents a search for a fatherly figure, some higher authority, if not God.

Both liberal capitalism and communism introduce a simplistic world of certainties with the overarching idea of God’s kingdom on earth a real possibility. Short of that, there wouldn’t have been the Soviet Union, nor the global empire of the West. That is why Francis Fukuyama’s end of history remark wasn’t a slip of a tongue. Vladimir Mayakovsky in his Left March in 1920-ies called to ride the old nag of history to death. That certainty and setting ultimate/final objectives in societal development were the things that communism and liberal capitalism had in common, though the formulas and languages differed. In both cases it required a measure of totalitarian control, albeit differently exercised. But the outcomes were pretty similar, making George Orwell’s organization of society around trough somewhat universal, with some being more equal than others.

Direct or indirect, coercion translates into conformism, which means giving up on freedom of expression and, most importantly, freedom of thought. The most important of A. de Tocqueville’s observations seems to be the one dealing with conformism, including in the form of aggressive parochialism, strangling life where it starts, i.e. in one’s head (a point left out by Niall Ferguson in his fourth Reith lecture on the BBC Radio 4). Conformism has been, traditionally, a mortal sin in Russian liberation movement and dissent, that attitude quiet often brought to the bitter end, including the assassination of Alexander II and the tragedy of 1917. One of the poignant moments in The Stilyagi is the episode when one of their company returns from the US and says that there are no stilyagi in America. Of course, Ken Kesey and J.D. Salinger had written their famous books by then, but they had not yet been read in the Soviet Union.

* * *

I completely agree (all the more so, that in Russia literature was, for the most of time, the only space for political thought and debate) that literary truth quite often is more compelling than political or philosophical analysis. Since Russia is a widely accepted case in that regard, I’d like to refer to books like One Flew Over Cuckoo’s Nest and The Catcher in the Rye (I remember what a hit it was in the Soviet Union, when it was published there in mid-60-ies). These books were a prophecy, which has been coming true over the past 30 to 40 years. They were more convincing on the state of American society, its limitations of existential nature, than the critical part of A. de Tocqueville’s analysis (its merit due to use of much broader categories, than, say, narrow bounds of the Cold War ideological debate). Similarly revelatory are films like Dr.Strangelove, Pulp fiction and Forrest Gump, (my daughter’s favourite since age of six) providing a narrative of life universally understood, which makes it possible for others to connect with America.

It is also easy to assume then, that suspected anti-Americanism of Nabokov’s Lolita is real and deliberate. Consumerism, the very essence of American life/dream is in direct opposition to what the Russian culture and spiritual values have always been about. Pitirim Sorokin, as a matter of fact, foresaw both the Soviet Union’s and the West’s demise precisely on those grounds. His prophecies coming true, are there any other explanations for this deep-down affinity and commonality of fates?

Tourgenev’s nostalgia is akin to Marcel Proust’s bidding farewell to la Belle époque symbolized in the image of the femme elegante. Not always in style, that life somehow bore resemblance to the XVIII-th century, its lost sense of the world, made obviously impossible by what Zb.Brzezinski called a mass political awakening. The European society’s contradictions led to WWI at another turn of the century which draw the line under previous experience, including horrors and human cost of the Industrial Revolution (it was a major breakthrough in terms of dehumanization of European society). Dostoyevsky visited London for the World Fair in 1863. It is there, in Hay Market, that he saw a girl of six years of age, in rags, who “walked with an air of such grief, such definitive despair in her face, that even to see this poor creature was unnatural and awfully painful”. That experience, as wrote Vassily Rozanov, strengthened Dostoyevsky’s last temptation, he would never overcome, that of rejection of innocent suffering.

Overall, in terms of the Industrial Revolution the uniqueness of Britain is understated. In comparison to it, the experience of the Empire comes as a distant second in terms of the self-inflicted suffering which scarred the British society and may explain the universal significance of English literature. This sublimation of suffering is the thing our two literatures have in common.

It is not only a matter of enclosures and Vagrancy laws, but a measure of denial of the lower classes’ humanity, which helped to diminish fellow human beings to mere labour as a commodity subject to the force of market element. What was more, labour was imparted a subliminal sense of guilt for its own condition.

The Industrial Revolution was, indeed, dehumanizing. True, the Pre-Raphaelites responded to its brutality and materialism with their art. Its destructive impact upon life was a recurring concern of D.H.Lawrence. In his Lady Chatterley, Horse-trader’s Daughter, Sun and other things he sort of finds Paradise lost, juxtaposing things tangible to the tactile and living warmth (the sweater Stalker never parts with). For sure, he would agree with the Stalker’s post-industrialism, as well as love in the Biblical sense of the word, maybe, as a miracle or a testimony to it. Leo Tolstoy said: “God is where love is”.

Our bard Vladimir Vysotsky had this line in one of his best songs: The sky is reflected in woods like in water. Marcel Proust’s personality is, for sure, reflected in his Young Girls in Bloom or a sleeping Albertine (naturally, the self-portraits of Louise Vigée Le Brun and Zinaida Serebriakova come to mind, followed by Gustave Courbet’s La Belle Irlandaise, and for that matter, the symphonies by James Whistler). In a similar way, that of Stalker is reflected in the postindustrial landscape. It is worth mentioning that O.Spengler thought that the spread of the English landscape park on the continent (maybe, as something that is more in harmony with nature) at the turn of the XIX-th century was a sign of the shape of things to come, i.e. the oncoming Anglo-Saxon domination within the West.

It is also striking that in different films (and books) on the post-war time, including the Soviet Union and Italy, there was some kind of common denominator of humanity. Maybe, it is because it was about simple, basic things of life, daily bread, bare necessities like providing for a family, having enough food for kids? This overall cultural and spiritual affinity with Italy is striking (Fellini’s Amarcord etc.). And was difficult life of the Depression years not more human than that of the 70 to 80-ies, when the Western society had never had it so good?

It seems that some essential quality of life was lost in the 60-ies on both sides of the Cold War divide, when, maybe true, all of us, in different ways, started to live in debt. But is it the reason for the present crisis or just a symptom of a deeper, more fundamental illness of our life gone astray? It is only proper, that the accusation most often leveled against political elites in the West is that the governments are rather about style than substance. And if the style is not about substance and the truth, but in their stead, then this is the real reason for where we are at the moment.

Globalization vs. reality is also and interesting subject. In the summer of 1917 Alexander Kerensky while seeing the troops off to the front talked about the things we now call globalization. But that couldn’t change the reality which was Russia’s inability or indisposition to fight. As a result of this gap, the Bolsheviks came to power.

Chekhov in his plays already spoke of some huge voids in life (for example, in Three Sisters). Vassily Rozanov in his Apocalypse of Our Time (immediately after the 1917 Revolution in Russia) came to the conclusion that those voids in human soul, which caused the Russian and European catastrophe, had been left by former Christianity. To him, like to Dostoyevsky, attempts to organize society outside/without God were clearly to blame. You mention W.H.Auden. He said (translation from Russian from Georgy Adamovich’s Solitude and Freedom): “It is impossible to build a human society upon what Dostoyevsky told us. But a society, that forgets what he said will not deserve being called human”.

The Room, its destruction or entering it, mean an end to human existence. Lost hope or fulfilment of innermost desires were equally frightening prospects. To be quite frank, we in Russia, somewhere deep in heart, have always had this vague fear of what to do next when we reach those prosperity and normality, intuitively suspecting that to be the end of the road. Consciously or not, we followed this maxim: “Look for God’s kingdom first and the rest will be rendered unto you.” As Vassily Rozanov put it, we didn’t read it vice versa. At least our history can be explained that way, if not justified. Dostoyevsky’s underground man writes: “Is it not that the man likes destruction and chaos so much that, instinctively, he is afraid of reaching the objective and finishing the construction of the building, which he may like from afar, but does not like living in it?”

* * *

On The Stalker’s language and method. It is no wonder that all great authors, who had something to say (Shakespeare, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, D.H.Lawrence), were in need of their own language to get their message across. The Stalker’s genre is very close, in its mix of words, images and sounds, to parables of the Bible. In the poem Silentium (around 1830) F.Tyutchev wrote: “A thought uttered is a lie”.

The method (Methodism?) follows Dostoevsky’s fantastic realism, i.e. an utterly artificial plot/construction to make characters bare their souls. This is a Transfiguration, which Dostoevsky himself experienced when waited for execution and then in Siberia. Stalker had had similar experience, which leads to a revelation. So, GULAG here is a means to an end, which is spiritual renaissance. He helps Writer and Professor to pass the same test, and it is easy to believe that their lives will never be the same. And it is the truth of human nature (human beings ourselves, we always recognize it when we come across it) that makes his works realistic. Stendhal also used this method, for example, in The Scarlet and the Black, to make his point.

Downshifting, when people leave the established economy to regain control of their lives, is a sign of our uncertain times, an almost universal response (from Italy to Ireland) to the present crisis. One doesn’t need reading Simone Perotti’s books to convert to this faith. In a sense, it draws a line under and a conclusion from our common history and experience of the past three to five centuries at least, and condemns all the progress we have achieved up to now. Perhaps, not progress per se, but the method which it has been achieved by. But it is the method that ultimately defines the outcome. It would be fair to say that for many Russians sort of downshifting has been a regular mode of existence, to a different degree at various times. That provides a fitting definition of Stalker’s life (by daily bread, among other things).

Maybe, now is the time to learn from static societies of the past, giving up on the paradigm of economic development, based on relentless growth and speed of operations, both of which reached the point of unsustainability and incompatibility with human nature. Perhaps, Japan, through its painful experience of the past 20 years, having been part of the West and now returning to its Asian roots, while building its economy down to preserve its identity, provides an example to follow.

It takes particular sensibility to hear something still alive buried in our soul under a heap of things and permanent lack of time to spare to contemplation and feeling. It helps to know or just suspect, that things like that exist in principle. Afterwards, they start acquiring flesh and blood of one’s own thoughts and experience. Watching The Stalker serves that end. In that regard this film was as subversive for the Soviet system, as for the Western one.

The categories of convergence and synthesis seem to be the way to answer all the problems of the European family, including Russia and Britain. Historically, it has always been the case in the postwar Europe, given socialization of its economy in response to geopolitical imperatives of the Cold War. Wrong conclusions were drawn after its end, which probably explains much of the present state of the Western societies, weighted down by the attempts of the XIX century capitalism to take revenge upon the XX century capitalism with a human face. That is why quite a few scholars believe that the present vacuum of ideas might be overcome through neoclassical synthesis of the products of European thought of 60-ies, including existentialism and developmentalism, on the basis of collective analysis of the combined experience of the Soviet Union and the West. For that, we have to go beyond narrow constraints of the Cold War ideological discourse.

To sum it up, it is against this background, distinctly Russian, but also European in many regards, that The Stalker may be looked at. I would call it an utterly timely reminder of our Christian roots, that we forgot and betrayed in different ways. The question is, if it is still possible to reconnect and how. Existentialism tried it in the 60-ies, but then was forgotten, especially with the end-of-history mood after the Cold War was over.

Overall, to me the film testifies to the single most important fact of Russia losing its distinctiveness, but for one thing, i.e. residual ability to ask Life Questions. Fyodor Tyutchev coined a very controversial phrase: “By the very fact of her existence Russia denies the West’s future.” (He, by the way, wrote in late 1840-ies that there was place in Europe for a Germany as federation, not as an empire, which would be, and was, disastrous for the continent.) It doesn’t sound that much aggressive nor chauvinistic now that we have seen the end of the Soviet Union and have been eyewitness to the present global crisis, which qualifies as a crisis of liberal capitalism or that of Western society. Karl Jaspers, in fact, somehow agreed with that, when he wrote in his “Origin and Goal of History” of Asia as “a necessary addition” to Europe, which “was not on the way of improving human nature.” That is why, it is not the West vs. the Soviet Union, since both were pretty much close existentially, but the West vs. the sense of the world that the Soviet Union tried to destroy. The Stalker makes the difference against the background of convergence and synthesis of the two parts of European civilization. Vladimir Solovyov made this point: synthesis in the realm of the moral equals reconciliation, which also means treating your enemy in a human way. Karl Jaspers thought that the human nature in its entirety can only be revealed in synthesis of all phenomena in which it expresses itself. Whatever the final outcome of the crisis, this ability to disturb conscience and mind might be helpful to us all.

F.Dostoyevsky wrote about a single reminiscence of childhood, that might save a person in his/her life (in fact, Chapter 10 “Boys” of The Karamazov Brothers covers this subject). What reminiscence of that type for Europe? Maybe, that of the age of Christianity. M.Albright (in her book The Mighty and the Almighty of 2006) wrote, that people in Islamic countries now “concern themselves with transcendent issues of history, identity, and faith. To be heard, the rest of us must address matters equally profound”. The very idea of progress will have, perhaps, to be redefined along those lines.

It is probably the time to subject the very foundations of our life to the ultimate test of whether they relate, and to what extent, to real needs of human existence. Maybe, the one-sided construction of human nature of a few centuries ago has proved to be wrong. After all, we cannot make judgment on a tree ignoring the fruit it bears. Everything was supposed to be built upon reason, common sense and common decency. Where are they? Have worn out?

Maybe, now is the time to find out what was lost in this translation of Christianity, that is still alive deep down in our soul and once in a while is dragged out to day light by people like Dostoyevsky and Tarkovsky, testifying to an utterly wanting definition of humanity, we have long resigned ourselves to living with.

Finally, thank you for your observation on watching people drinking in films. It is great.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

20:11 21.11.2013 •

20:11 21.11.2013 •