The record of Slovakia's Rusyns seems to occupy a modest niche within the general framework of the history of Rusyns of Transcarpathia or Hungary, which is explainable considering that for centuries both Transcarpathia (also known as Uhorská Rus) and Slovakia used to belong to Hungary and, therefore, the country held sway in the Rusyn affairs. There is no reason to overlook the dramatic, albeit local theme of the Rusyns of Slovakia whose existence over various epochs was rich in inspiring developments and bitter disappointments. All of the milestones of the past of Slovakia's Rusyns are impossible to mention is a brief paper, and what follows is essentially an attempt at an overview of the important part of the West-Russian history reflected in the story of Slovakia's Rusyns.

You will hardly find another branch of Russian life as distant from the stem of it as Presov (Priashiv) Rus'. The name can be traced back to the 1920ies, the time when the Rusyns of Slovakia thus christened their lands centered around Presov as they were separated by country borders from the rest of Uhorská Rus. Preserving their distinctiveness and language was a key challenge for Rusyns in Slovakia no less than in Hungary where switching to the Magyar identity was commonplace and, in fact, a whole new term “Magyaron” was coined to describe non-Hungarians fully adopting the Hungarian ways. Consensus has not been reached till, for example, whether Hungarian poet Sándor Petőfi was a Slovak or a Serb turned Hungarian, but it is clear that, in either case, he was not a Hungarian in the ethnic sense.

Rusyns in Serbia where Ruski Krstur was the epicenter of the Rusyn culture similarly struggled to keep their original language. The town is chiefly known as the homeland of Protopresbyter Gabriel (Havriil) Kostelnik, a Uniate priest who returned to the Orthodox Church and an ecclesiastic leader, theologian, philosopher, religious publicist, poet, playwright and prose-writer remembered for urging all Uniates to reunite with the Orthodoxy. Fr. Gabriel was assassinated in 1948 in Lviv by a terrorist from the Ukrainian Rebel Army (UPA). The killer committed suicide immediately after the deadly assault, apparently out of fear of justice being delivered by chance witnesses of the crime. Up to these days, there is still no memorial sign at the site of Fr. Gabriel's martyrdom, while monuments to UPA guerrillas are ubiquitous in Lviv.

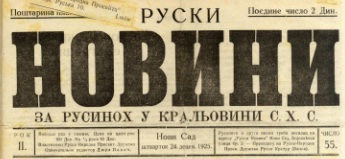

Ruski Novini newspaper, 1925, (The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes)

While Rusyns in the Soviet Union had to resist Ukrainization, the pressure on their brethren in Czechoslovakia was in fact double as two identities – Ukrainian and Slovakian – were being imposed on them simultaneously. Explaining the motivation behind the policy, Carpathian-Russian historian A. Gerovski cited Czechoslovakia's education minister Vavro Srobar as saying that no Rusyn would agree to switch from literary Russian to Czech or Slovakian, but competing against Ukrainian was a completely realistic objective [1]. The situation had the same contours in Transcarpathia where Rusyns were en masse listed as Ukrainians or even Slovaks in public records. Slovak origin was ascribed to Rusyns who did not even know the Slovakian language but had been born in Slovakia, the result being that, in some cases, children of the same parents became people with officially different nationalities.

The policy of slapping either Ukrainian or Slovakian identities on Rusyns persisted into the Communist era in Czechoslovakia. The treatment was the likely reason why Rusyns in the country largely welcomed the 1968 Soviet invasion and opposed Prague rather than Moscow. The Soviet policy of Ukrainization certainly stayed on the Rusyn's grievances list, but their traditional loyalty to Russia outweighed all other regards.

An opportunity to move to the USSR opened up to Slovakia's Rusyns starting in 1940. Those who seized it oftentimes ultimately felt that they had made a huge mistake as the Soviet government accommodated the incoming Rusyns on the western rim of Ukraine where Ukrainian nationalism was pervasive and the population proved to be quite unfriendly. Pro-Russian and critical of all brands of radical nationalism, Rusyns were bound to meet with a hostile reception in this new homeland, and, till the very 1960ies, some of them trickled back into Slovakia where, at least, they were not exposed to insults or threats for Russophile leanings.

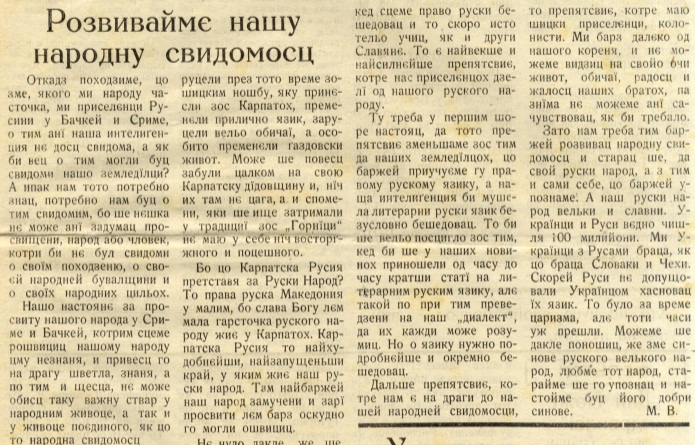

«Cultivating Our National Awareness» - a Rusyn newspaper published in The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes compares Carpathian Ruthenia to Macedonia, describes it as a deeply impoverished region, and says that Ukrainians and Russians are one nation

By design, the rampant Ukrainization across Presov Rus' helped to even out the non-Slovak component of the region's character. The Rusyn society split, with some accepting the status of Ukrainians and others staunchly rejecting it. The Russian-oriented Rusyns ended up being cut off from the sources of information in literary Russian, and the indigenous dialect of the isolated community increasingly evolved towards Ukrainian. The unintended linguistic drift seemed to warrant the policy of discounting the Russianness of the Rusyn mother tongue.

In the post-Soviet epoch, the administration of independent Ukraine invented a politically expedient concept of “Ukrainian Rusyns”, the truth being that absolutely no traces of the phenomenon can be discovered in real-world history. Even a fleeting glimpse of the map of Slovakia reveals a series of toponyms pointing to the Russian roots of their original populations – Ruský Potok, Ruská Bystrá, Ruský Hrabovec - but the adjective “Ukrainian” never pops up.

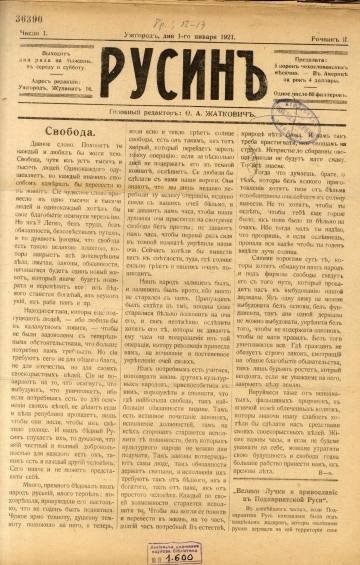

Rusyn, a newspaper published by Rusyn political activist F.A. Zhatkovich (Uzhhorod, 1921)

Will Rusyns succeed in reaffirming their identity of descendants of scattered ancient Rus' or will the ruthless machinery of Ukrainian nationalism grind them up as the pro-western Kyiv administration plans to? As of today, the Rusyns in Slovakia are in a considerably better position than in Transcarpathia. Presov Rus' maintains a system of schools and preschools with instruction in Rusyn, and even the relations between the Rusyn and Ukrainian communities in Slovakia, where the Ukrainians have not been brainwashed into radical nationalism and are not uniformly hateful vis-a-vis Rusyns, are a lot more normal than in Transcarpathia.

It says volumes that Rusyn schools function in Slovakia, Serbia, etc. but are nowhere to be found in Ukraine. There is every indication that for Kyiv Rusyns are an obstacle in its way, an ethnic disturbance which is to be averaged out.

[1] A. Gerovski, The Czech Government's Struggle Against the Russian Language (Routes of History Publishers), Volume II, p. 93-124

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

17:33 17.09.2014 •

17:33 17.09.2014 •