It's not every day you spot an armed robber or pirate in the distance. That's exactly what happened to a seafarer as a cargo ship slowed through the choke point of the Phillip Channel, which links the Malacca Strait to the South China Sea.

"We have seen a massive increase compared to last year," said maritime security expert Maximilian Reinold, ‘ABC’ edition from Australia writes.

From January to June this year, 95 incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships in Asia were reported — up 83 per cent compared to the same period last year.

That's according to The Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP), the biggest institution gathering data on these maritime attacks.

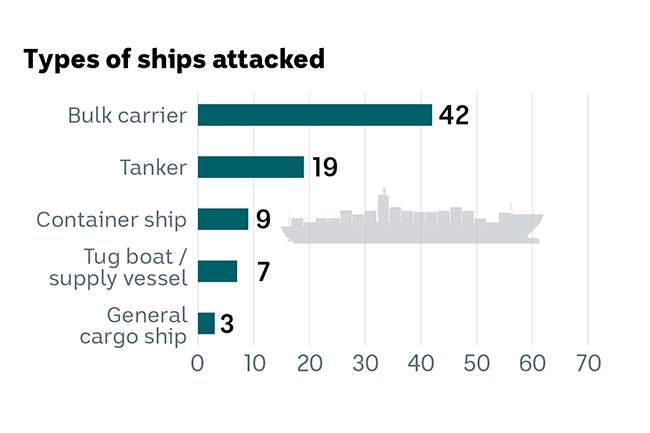

"The typical pirate here is mostly targeting bulk ships, it's usually two, maybe four people in small and relatively fast boats, but it's not like the typical crime you see off Somalia of hijacking," Mr Reinold, from the Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, said.

How important is the Malacca Strait?

Most of these crimes are committed in the straits of Malacca and Singapore, which are among the world's busiest shipping lanes.

Recent sea robberies and pirate attacks aria. (ABC News)

Recent sea robberies and pirate attacks aria. (ABC News)

Roughly two-thirds of Australian exports pass through these narrow waterways between Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, including precious commodities like coal and gas.

China and Singapore also rely on the straits for fuel supplies to run their economies.

"When the industry body JWC declares a change in status of a waterway such as a 'war-risk area', insurance fees go up," Daniel Ng from Vanguard-Tech. said.

The Joint War Committee (JWC) is a London-based administrative body responsible for identifying areas where there is a heightened risk of things like war, terrorism and piracy.

Although there has been a rise in sea robberies, the Malacca Strait has not been placed on its high-risk list.

But Mr Ng said a similar wave of pirate attacks in the mid-2000s prompted insurers to classify the strait a "war-risk zone", doubling premiums and increasing costs across the supply chains.

Who are the pirates?

The narrow and busy waterway of Phillip Channel, off Indonesia's Pulau Cula, has been a particular hotspot for pirates this year.

"The pirates and sea robbers tend to be low-level opportunists from the remote islands in Indonesia's Riau Islands," Thu Nguyen Hoang Anh, a PhD candidate in public policy at the National University of Singapore, said.

"They usually are armed but rarely violent."

The Malacca Strait is a choke point on the route between the Middle East and the energy-hungry economies of East Asia

The Malacca Strait is a choke point on the route between the Middle East and the energy-hungry economies of East Asia

Piracy is escalating in the Phillip Channel. (ABC News)

She said the labyrinth of remote islands made it easy for a quick getaway for the little boats after robberies.

For now, most incidents cause little harm beyond stolen goods.

No hostages, no guns, just quick grab-and-go raids.

Experts agree that the spike is driven by economic hardship, but there is debate over who is behind it: struggling locals or organised gangs.

Mr Ng said many suspects likely came from Bintan or Batam, islands south of Singapore still struggling after the pandemic devastated tourism.

"Their living conditions are very difficult, so to survive they commit these petty crimes," he said.

But recent arrests in Indonesia suggest the picture is complicated, with the suspects tied to organised crime rather than opportunistic fishermen.

Evidence is inconclusive, yet analysts said it was likely that offenders possessed maritime backgrounds.

Coordination for attacks

Mr Ng said he saw evidence of organised crime.

He said gangs coordinated attacks after obtaining shipping data and organising "foot soldiers" in WhatsApp groups to conduct the raids.

"Let's go to party" was code for robbing a boat, according to Mr Ng's sources.

"The guys who will go on the ships are like the foot soldiers," Mr Ng said, estimating they earn a few hundred US dollars per operation — enough to live on for months in Indonesia.

He said he believed the lure was making quick cash on the black market.

"They are stealing spare parts that are easily sold in the market, so it can be used by shipyards or any other companies that require such spares," Mr Ng said.

"There is an ecosystem here where there is a [syndicate] coordinator for how they are going to sell off stolen items."

Source: ReCAAP ISC Half-Yearly Report 2025

Source: ReCAAP ISC Half-Yearly Report 2025

Donald Rothwell, an expert in international law from the Australian National University, said one of the thorniest problems in tackling piracy for South-East Asian states was jurisdiction.

"Let's take the example of the Singaporean police and coast guard witnessing an active sea robbery in the Singaporean territorial sea," Professor Rothwell told the ABC.

"As soon as that vessel crosses into the Malaysian or Indonesian territorial sea, the Singaporean authorities have to stop."

For now, the burden to control piracy on these routes falls on Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia, whose waters generate billions in revenue from international shipping.

Mr Rothwell said there were examples of treaties, such as one between Australia and France which allows the two nations to chase illegal fishing vessels into each other's waters near their sub-Antarctic islands.

But he warned that the strait states remained sensitive to outside involvement.

"They very much say this is their responsibility, their burden, their obligation," he said.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:59 26.09.2025 •

10:59 26.09.2025 •