Military spending is rising faster than at any time since the Cold War, but the retreat from diplomacy and foreign aid will come with a price, POLITICO notes.

One school of academic theory holds that era-defining wars recur roughly every 85 years, as generations lose sight of their forebears’ hard-won experience. That would mean we should expect another one anytime now.

And yet, as Andrew Mitchell, a former Cabinet minister in the British governmentб sees it, even as evidence mounts that the world is headed in the wrong direction, governments have lost sight of the value of “jaw-jaw.”

The erosion of diplomatic instinct is showing up not just in rhetoric but in budgets. The industrialized West is rapidly scaling back investment in soft power — slashing foreign aid and shrinking diplomatic networks — even as it diverts resources to defense.

At no point since the end of the Cold War has military spending surged as fast as it did in 2024, when it rose 9.4 percent to reach the highest global total ever recorded by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

By contrast, a separate report from the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found a 9 percent drop in official development assistance that same year among the world’s richest donors. The OECD forecast cuts of at least another 9 percent and potentially as much as 17 percent this year.

Diplomatic corps are also shrinking, with U.S. President Donald Trump setting the tone by slashing jobs in the U.S. State Department.

Global figures are hard to come by, and anyway go out of date quickly; one of the most extensive surveys is based on data from 2023. But authorities in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the European Union’s headquarters are among those who have warned that their diplomatic staff face cuts.

Analysts fear that as industrialized economies turn their backs on aid and diplomacy to build up their armies, hostile and unreliable states will step in to fill the gaps in these influence networks, turning once friendly nations in Africa and Asia against the West.

And that, they warn, risks making the world a far more dangerous place. If the geopolitical priorities of governments operate like a market, the trend is clear: Many leaders have decided it’s time to sell peace and buy war.

Selling peace, buying war

Military spending is climbing worldwide. The Chinese defense budget, second only to that of the U.S., grew 7 percent between 2023 and 2024, according to SIPRI. Russia’s military expenditure ballooned by 38 percent.

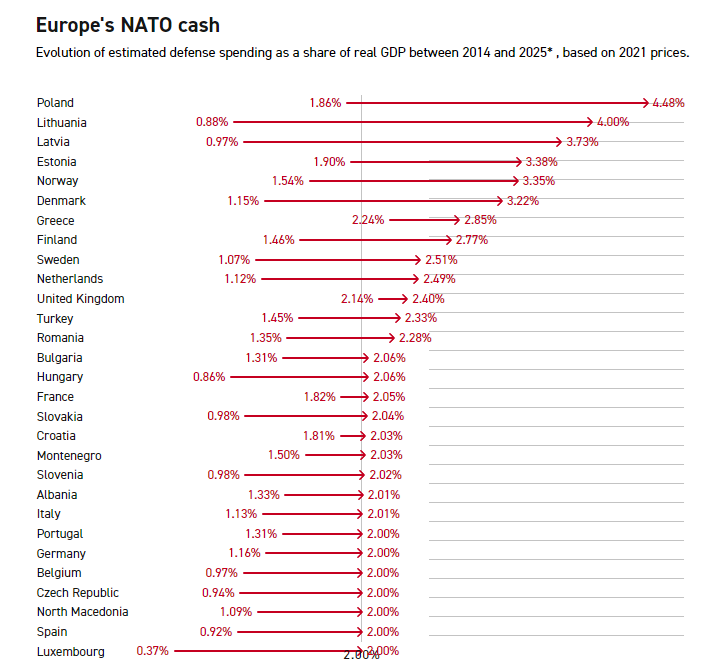

Spurred in part by fears among European countries that Trump might abandon their alliance, NATO members agreed in June to a new target of spending 5 percent of gross domestic product on defense and security infrastructure by 2035. The U.S. president — cast in the role of “daddy” — was happy enough that his junior partners across the Atlantic would be paying their way.

In reality, the race to rearm pre-dates Trump’s return to the White House. The war in Ukraine made military buildup an urgent priority for anxious Northern and Eastern European states living in the shadow of President Vladimir Putin’s Russia. According to SIPRI, military spending in Europe rocketed 17 percent in 2024, reaching $693 billion — before Trump returned to office and demanded that NATO up its game. Since 2015, defense budgets in Europe have expanded by 83 percent.

Military expenditure on the rise

One argument for prioritizing defense over funding aid or diplomacy is that military muscle is a powerful deterrent against would-be attackers. As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it when she announced her plan to rearm Europe in March: “This is the moment for peace through strength.”

Some of von der Leyen’s critics argue that an arms race inevitably leads to war.

Few serious politicians in Europe, the U.K. or the U.S. dispute the need for military investment in today’s era of instability and conflict. The question, when government budgets are squeezed, is how to pay for it.

Evolution of estimated defense spending as a share of real GDP between 2014 and 2025, based on 2021 prices:

NATO collected data until June 3, 2025. 2024 and 2025 data are estimates. In previous years, countries may have met the 2 percent spending target when using then-available GDP data.

Source: NATO /POLITICO

But Sweden’s international development cooperation budget, which was worth around €4.5 billion last year, will fall to €4 billion by 2026.

In debt-ridden France, plans were announced earlier this year to slash the ODA budget by around one-third, though its spending decisions have been derailed by a spiraling political crisis that has so far

Jaw-jaw or war-war?

Mitchell, the former British Cabinet minister, warned that the accelerating shift from aid to arms risks ending in catastrophe.

“At a time when you really need the international system … you’ve got the massive resurgence of narrow nationalism, in a way that some people argue you haven’t really seen since before 1914,” he said.

Mitchell, who was the U.K.’s international development minister until his Conservative Party lost power last year, said cutting aid to pay for defense was “a terrible, terrible mistake.” He argued that soft power is much cheaper, and often more effective, than hard power on its own. “Development is so often the other side of the coin to defense,” Mitchell said. It helps prevent wars, end fighting and rebuild nations afterward.

Many ambassadors, officials, diplomats and analysts interviewed for this article agree. The pragmatic purpose of diplomatic networks and development programs is to build alliances that can be relied on in times of trouble.

“Any soldier will tell you that responding to international crises or international threats, isn’t just about military responses,” said Kim Darroch, who served as British ambassador to the U.S. and as the U.K.’s national security adviser. “It’s about diplomacy as well, and it’s about having an integrated strategy that takes in both your international strategy and your military response, as needed.”

Hadja Lahbib, the European commissioner responsible for the EU’s vast humanitarian aid program, argues it’s a “totally” false economy to cut aid to finance military budgets. “We have now 300 million people depending on humanitarian aid. We have more and more war,” she told POLITICO.

The whole multilateral aid system is “shaking” as a result of political attacks and funding cuts, she said. The danger is that if it fails, it will trigger fresh instability and mass migration.

Countries that cut their outreach programs also face paying a political price for the long term. When a wealthy government closes its embassy or reduces aid to a country needing help, that relationship suffers, potentially permanently, according to Cyprien Fabre, a policy specialist who studies peace and instability at the OECD.

“Countries remember who stayed and who left,” he said.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:33 20.11.2025 •

11:33 20.11.2025 •