Pic.: Discovery Alert

Pic.: Discovery Alert

The White House has told companies they must rebuild Venezuela's crude-pumping infrastructure if they want compensation for assets seized by Caracas.

American oil companies have long hoped to recover the assets that Venezuela’s authoritarian regime ripped from them decades ago.

Now the Trump administration is offering to help them achieve that aim — with one major condition.

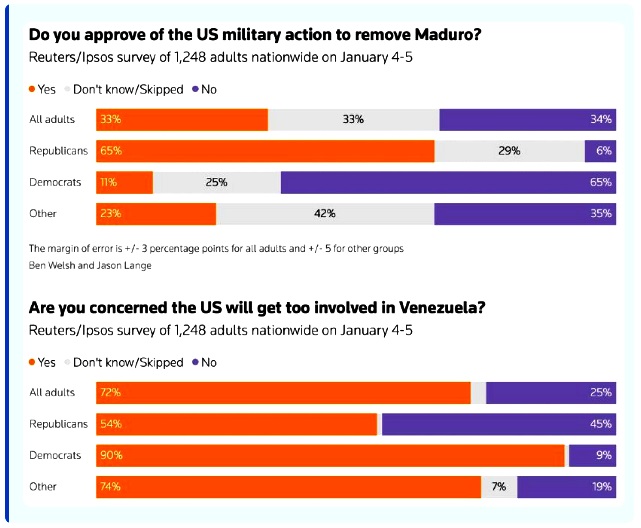

Administration officials have told oil executives in recent weeks that if they want compensation for their rigs, pipelines and other seized property, then they must be prepared to go back into Venezuela now and invest heavily in reviving its shattered petroleum industry, two people familiar with the administration’s outreach told POLITICO. The outlook for Venezuela’s shattered oil infrastructure is one of the major questions following the U.S. military action that captured leader Nicolás Maduro.

The people in the industry are not so optimistic as Mr.Trump

But people in the industry said the administration’s message has left them still leery about the difficulty of rebuilding decayed oil fields in a country where it’s not even clear who will lead the country for the foreseeable future.

“They’re saying, ‘you gotta go in if you want to play and get reimbursed,’” said one industry official familiar with the conversations.

The offer has been on the table for the last 10 days, the person said. “But the infrastructure currently there is so dilapidated that no one at these companies can adequately assess what is needed to make it operable.”

President Donald Trump suggested in a televised address Saturday morning that he fully expects U.S. oil companies to pour big money into Venezuela.

“We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure, the oil infrastructure and start making money for the country,” Trump said as he celebrated Maduro’s capture.

It’s been five decades since the Venezuelan government first nationalized the oil industry and nearly 20 years since former President Hugo Chávez expanded the asset seizures. The country has some of the largest oil reserves in the world, but its petroleum infrastructure has decayed amid years of mismanagement and meager investment.

A central concern for U.S.

A central concern for U.S. industry executives is whether the administration can guarantee the safety of the employees and equipment that companies would need to send to Venezuela, how the companies would be paid, whether oil prices will rise enough to make Venezuelan crude profitable and the status of Venezuela’s membership in the OPEC oil exporters cartel. U.S. benchmark oil prices were at $57 a barrel, the lowest since the end of the pandemic, as of the market’s close on Friday.

The White House did not immediately reply to questions about its plan for the oil industry, but Trump said during Saturday’s appearance at his Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida that he expected oil companies to put up the initial investments.

“We’re going to rebuild the oil infrastructure, which requires billions of dollars that will be paid for by the oil companies directly,” Trump said. “They will be reimbursed for what they’re doing, but it’s going to be paid, and we’re going to get the oil flowing.”

However, the administration’s outreach to U.S. oil company executives remains “at its best in the infancy stage,” said one industry executive familiar with the discussions, who was granted anonymity to describe conversations with the president’s team.

“In preparation for regime change, there had been engagement. But it’s been sporadic and relatively flatly received by the industry,” this person said. “It feels very much a shoot-ready-aim exercise.”

Venezuela’s oil output has fallen to less than a third of the 3.5 million barrels per day that it produced in the 1970s, and the infrastructure that is used to tap into its 300 billion barrels of reserves has deteriorated in the past two decades.

Chevron, the sole major oil company still working in Venezuela under a special license from the U.S. government, said in a statement Saturday that it “remains focused on the safety and wellbeing of our employees, as well as the integrity of our assets.

Promoting U.S. investment in Venezuela

Richard Goldberg, who led the White House’s National Energy Dominance Council until August, said the Trump administration could offer financial incentives to coax companies back into Venezuela.

Promoting U.S. investment in Venezuela would keep China — a major consumer of Venezuela’s oil — out of the nation and cut off the flow of the discounted crude that China buys from Venezuela’s ghost fleets of tankers that skirt U.S. sanctions.

“There’s an incentive for the Americans to get there first and to ensure it’s American companies at the forefront, and not anybody else’s,” said Goldberg.

It’s unclear how much the Trump administration could accelerate investment in Venezuela, said Landon Derentz, an energy analyst at the Atlantic Council who worked in the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations.

Many consider Venezuela a longer-term play given current low prices of $50 per barrel oil and the huge capital investments needed to modernize the infrastructure, Derentz said. But as U.S. shale oil regions that have made the country the world’s leading oil producer peter out over time, he said, it would become increasingly economical to export Venezuelan heavy crude to the Gulf Coast refineries built specifically to process it.

“Venezuela would be a crown jewel if the above-ground risk is removed. I have companies saying let’s see where this lands,” said Derentz, who served in Trump’s National Security Council during his first term. “I don’t see anything that gives me the sense that this is a ripe opportunity.”

María Corina Machado dreams of revenge. But Trump is against it

The Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado has vowed to return to the country as soon as possible and rejected the authority of the interim president backed – for now – by the US after it forcibly removed Nicolás Maduro from power.

Many in Venezuela and abroad had expected Machado to take charge of the country after Maduro’s detention on Saturday, but Trump sidelined her and gave his backing to Maduro’s former vice-president, Delcy Rodríguez.

The industrial engineer, 58, also said she had not spoken Trump since 10 October, the day it was announced that she had won the Nobel peace prize.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Trump had decided to back Rodríguez after CIA analysts briefed him that Machado and her electoral candidate, the retired diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia, “would struggle to gain legitimacy as leaders while facing resistance from pro-regime security services, drug-trafficking networks and political opponents”.

The Washington Post, however, reported the decision may have been more personal, that Trump may have been irritated that Machado accepted the prize. “If she had turned it down and said: ‘I can’t accept it because it’s Donald Trump’s,’ she’d be the president of Venezuela today,” a source told the paper.

Trump has said he wants to work with Rodríguez and the rest of Maduro’s former team provided that they submit to US demands on oil. He has poured cold water on the idea that a vote could be held within the next 30 days.

The Venezuelan government made public a “state of external commotion”

On Monday the Venezuelan government made public a decree dated Saturday and signed by Maduro – who was arrested at 2.01am – declaring a “state of external commotion”, effectively a state of emergency, and ordering the “immediate search and capture of anyone involved in the promotion or support of the US armed attack”.

Beyond the pursuit of those accused of supporting the US attack – a task made more complex by the widespread belief that senior government figures, including the acting president, may have provided crucial information leading to Maduro’s capture – the decree orders the mobilisation of the armed forces, mandates the militarisation of all public service infrastructure, the oil sector and basic state industries, and suspends the right to public assembly and protest.

At least 14 journalists and media workers, including 13 linked to international outlets, were detained in Caracas on Monday. Thirteen were later released, one of whom was deported.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:29 10.01.2026 •

10:29 10.01.2026 •