Aerial View of Haifa oil refineries.

Photo: Couterpunch

“Why, I wondered, would Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the Biden administration risk their standing in the world and ignore calls for a ceasefire? Did they have an unspoken agenda?” – writes Peter Beinart, editor of Jewish Currents.

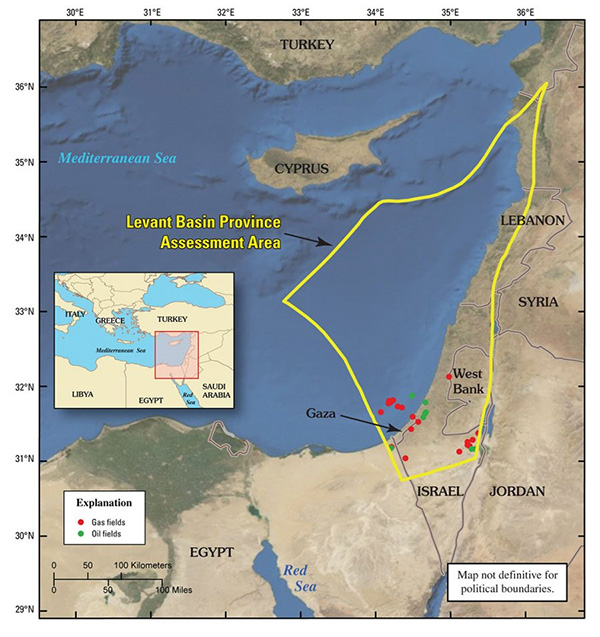

As a chronicler of the endless post-9/11 wars in the Middle East, I concluded that the end game was likely connected to oil and natural gas, discovered off the coast of Gaza, Israel and Lebanon in 2000 and 2010 and estimated to be worth $500 billion. The discovery promised to fuel massive development schemes involving the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Also at stake was the transformation of the eastern Mediterranean into a heavily militarized energy corridor that could supply Europe with its energy needs as the war in Ukraine dragged on.

Here was the tinderbox waiting to explode that I had predicted in 2022. Now it was exploding before our very eyes. And at what cost in human lives?

Map of the Eastern Mediterranean region showing the area included in the USGS Levant Basin Province assessment:

The year 1975 was my last in beautiful, cosmopolitan Beirut, Lebanon, before it descended into 15 years of brutal civil war, killing 100,000 people.

As a journalist for the Beirut Daily Star, I began reporting on the escalating tensions among the ruling Maronite Christians, Shiite Muslims — located primarily in southern Lebanon not far from the border with Israel — and the Palestinians caught in between.

Those three years of reporting in the Middle East gave me a rare lesson in how oil was turning desert sheikhdoms into modern city states, and Beirut into a refuge for the rich — but also a refuge for displaced Palestinians, which ultimately would not be tolerated.

By the mid-1990s, I was drawn back to writing about the Middle East, which was always in my heart, having been born in Beirut and having attended high school there — which was the beginning of my political awakening. But this time I was on a personal mission. I decided to investigate the circumstances behind the plane crash that killed my father. I was six weeks old at the time. Daniel Dennett had just completed a top secret mission to Saudi Arabia in March 1947.

As head of counterintelligence for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and its successor, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), his assignment was to determine the route of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline (aka Tapline) and whether it would terminate in Haifa, Palestine, soon to be Israel, or nearby Lebanon.

His last report stated that US oil executives were upset with Syria, which was refusing to let the pipeline cross Syrian territory.

This was remedied in 1949, when the CIA removed Syria’s democratically elected president, Shukri al-Quwatli, and replaced him with a Lebanese army officer who gave the green light to the pipeline crossing over Syria’s Golan Heights and terminating near the southern Lebanese port of Sidon.

Saudi oil, and the Trans-Arabian Pipeline which carried it to the Mediterranean Sea, was important to American ambitions in the Middle East. The New York Times, on March 2, 1947, carried a full page story about it entitled: “Pipeline for US Adds to Middle East Issues: Oil Concession Raises Questions Involving the Position of Russia.”

The article, written by President Harry S. Truman’s future son-in-law, Clifton Daniel, was a treatise on the “Great Game for Oil.” “Protection of that investment,” Daniel wrote, “and the military and economic security that it represents, inevitably will become one of the prime objectives of American foreign policy in this area, which already has become a pivot of world politics and one of the main focal points of rivalry between East and West.”

The East, of course, was the Soviet Union. And the US’s exclusive concession in Saudi oil would soon elevate it into becoming a world power, much to the consternation of not only the Soviets, but also the British and the French. Our erstwhile wartime allies were all quietly trying to undermine US interests in the Middle East.

In 1944, my father wrote in a declassified document that his mission for the OSS was “to protect the oil at all costs.”

After World War II, the US would replace a much-weakened Britain as the overseer of what was to become Israel.

In 2000, significant natural gas fields were discovered off the coast of Gaza and Israel. The Palestinians claimed that the gas fields off its coast, known as Gaza Marine, belonged to them. Arafat, now settled in the West Bank, hired British Gas (now the biggest energy supplier in the UK) to explore the fields. He learned they could provide $1 billion in badly needed revenue. “This is a Gift of God for our people,” Arafat proclaimed, “and a strong foundation for a Palestinian state.”

The Israelis thought otherwise. In 2007, Moshe Yaalon, a military hardliner (who would become Israel’s defense minister from 2013 to 2016) rejected claims by former British Prime Minister Tony Blair that the development of Gaza’s offshore gas by British Gas would bring badly needed economic development to the area. Although proceeds of a Palestinian gas deal could amount up to $1 billion, Yaalon asserted in a paper for Jerusalem Issue Briefs that the revenue “would not likely trickle down to an impoverished Palestinian people.” He insisted that the proceeds would “likely serve to fund terror attacks against Israel.” It is clear, he added, that, “without an overall military operation to uproot Hamas’s control of Gaza, no drilling work can take place without the consent of the radical Islamic movement.”

One year later, on December 27, 2008, Israeli forces launched Operation Cast Lead with the aim, Haaretz reported, of sending Gaza “decades into the past,” killing nearly 1,400 Palestinians and 13 Israelis. But it did not result in Israel gaining sovereignty over the Gaza gas fields.

In December 2010, prospectors discovered a much larger gas field off the Israeli coast, dubbed Leviathan. The field offered enough energy to supply Israel’s needs, but also presented Israel, according to the Hazar Strategy Institute, “with one of its greatest challenges: protecting the new offshore gas infrastructure in the Eastern Mediterranean which is vital to its energy security and therefore to its economic security.”

In the summer of 2014, Netanyahu launched a massive invasion of Gaza with the aim of uprooting Hamas and ensuring Israeli monopoly over the Gazan gas fields, killing 2,100 Palestinians, three-quarters of them civilians. Journalist Nafeez Ahmed, writing for The Guardian, claimed “resource competition has increasingly been at the heart of the conflict [in Gaza], motivated largely by Israel’s increasing domestic energy woes.” He continued, “In an age of expensive energy, competition to dominate regional fossil fuels is increasingly influencing the critical decision that can inflame war.”

After the 2014 invasion, the Gazan economy went into a free fall, exacerbating concerns about growing unrest.

Netanyahu has succeeded so far in averting questions about how Israel’s much vaunted security apparatus could have been taken by surprise by the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023.

He insists on calling October 7 “Israel’s 9/11,” even comparing how the Bush administration, like Israel, was “caught by surprise” by the terrorist attacks that day (in fact, Bush had been forewarned of an impending attack). Now Netanyahu had a pretext for justifying Israel’s latest and most brutal invasion of Gaza.

News has seeped out, however, that he was forewarned by Egyptian intelligence that Hamas was on the verge of orchestrating attacks in Israel. In fact, he was repeatedly warned by Israeli intelligence that the political turmoil surrounding his advocacy for changing the Israeli judiciary threatened Israeli national security.

Much of northern Gaza has been reduced to rubble, and it is his goal to obliterate southern Gaza as well. Perhaps he is thinking that only then, after destroying Hamas and forcing Palestinians out of Gaza, can he convince international lenders to support his long-held scheme of turning Israel into an energy corridor.

Netanyahu — and possibly President Joe Biden — are likely taking the “long view,” convincing themselves that the world will forget what happened once economic development takes off in the region, powered by Israel’s abundant offshore natural gas in the Leviathan Field and Gaza Marine. Work has already begun on another infrastructure project: building the so-called Ben Gurion Canal, from the tip of Gaza south into the Gulf of Aqaba, connecting Israel to the Red Sea and providing a competitor to Egypt’s Suez Canal.

The Canal Project will also connect Israel to Saudi Arabia’s $500 billion futuristic Neom tech city. One plan envisioned by the Abraham Accords involved normalizing relations with Israel, and tying the signatories — the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco — into vast development projects in the name of peace.

Ironically, at least for me, this involves a revival of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, only with its terminal point in Haifa, instead of Lebanon.

On the positive side, much of the world is now recognizing that there can be no development project, no peace process, that does not guarantee the military security of Palestine as well as Israel, and recognize the right of Palestinians to live free of occupation, with the same rights, dignity, and peace as their Israeli neighbors, stresses Peter Beinart.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:10 24.12.2023 •

10:10 24.12.2023 •