IN RECENT YEARS, much has been said about radicalism and its varied offshoots. True, the number of terrorist acts climbs up, the popularity of extreme right political forces grows, and the wave of left radical and anti-globalist movements, migration crises and international tension is rising. This is how everyday realities look in many countries of the world.

France is one of the European countries in which radical trends are only too obvious. At the 2017 presidential election, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, two radical politicians who represented anti-establishment political movements, reaped 41% and 51% respectively of the votes cast by young voters aged between 18 and 24. On the whole, the Fifth Republic is getting accustomed to violence against the law and order structures, destruction of material assets during rallies, protest acts that keep lyceums and universities blocked for a long time, and rejection of republican values that looked unshakable not long ago. Today, when fifty years separate us from the May 1968 events, we can talk about "banalization of protests" not only among the groups on the margins of society but also among its law-abiding part.

Late in 2015, after a series of terrorist acts in France a group of scientists, mostly sociologists of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) launched a large-scale research project to identify the factors responsible for the spread of radical ideas among the younger generation. In April 2018, the results were published in a monograph The Temptation of Radicalism one of the hits on the French book market.

The project is a unique one: for the first time, academic science turned its attention to the younger generation rather than to terrorist acts and those who commit them; it has become interested in the process of radicalization and the factors that plant the ideas of radicalism in the minds of high school students.

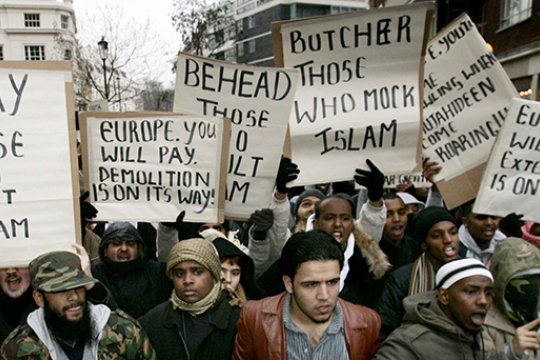

A vast, and most interesting, part of the book that deals with religious radicalism, one of the main objects of attention of the public and the media, offers two important conclusions that devalue the old and generally accepted opinions.

Sociologists have detected two component parts or two stages in religious radicalism: the "ideological" as devotion to the fundamentalist religious trends and "practical," the adepts of which are more than just religious fanatics - they justify violence for religious reasons.

The authors of the book under review who obviously prefer the term "religious absolutism" to "religious fundamentalism" have repeatedly pointed out that it is present in all world religions; the poll, however, revealed that religious absolutism was more typical of Muslim high school students.

Religion, or to be more exact, extreme Islamist trends combined with the male gender is the main factor of religious radicalization of the French youth.

This sociological study has demonstrated that the French national and confessional politics that for many years relied on the thesis that radicalization among the younger generation was caused by social and economic factors should be revised. This book made a great contribution to the broad and far from simple discussion of the place and role of Islam in French society, into which not only extreme right political movement are involved. In his speech of May 22, 2018, President of France "poured cold water" on the plan to shake up the banlieues devised by Jean-Louis Borloo. The president pointed out that more money poured into sensitive zones would not solve the main problem of radicalization.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

13:15 05.10.2018 •

13:15 05.10.2018 •