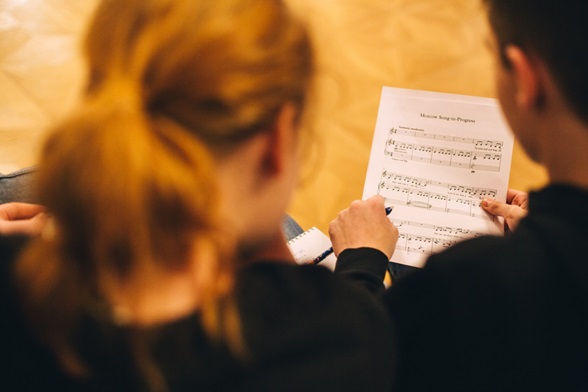

James Garner with the studio participants at MAMT

The year 2020 made us reconsider many familiar concepts, and it is hardly the end of the game. While the second wave of the pandemic sent much of Europe into another round of lockdowns it has become clear that transformations in many areas will continue. Culture and the arts are not an exception. We were not only deprived of the usual forms of communication with art, but also offered many new formats, even if they are not always familiar. In springtime the leading musical, and many drama theatres, conducted free broadcasts of their performances, soloists of ballet companies danced in home decorations, not to mention numerous educational platforms and courses, online exhibitions, fairs and online auctions. The audience has expanded to unprecedented sizes, and some figures are amazing. For example, during the first 3 months of the pandemic alone, performances of the Mariinsky Theatre were watched by 72 million spectators.

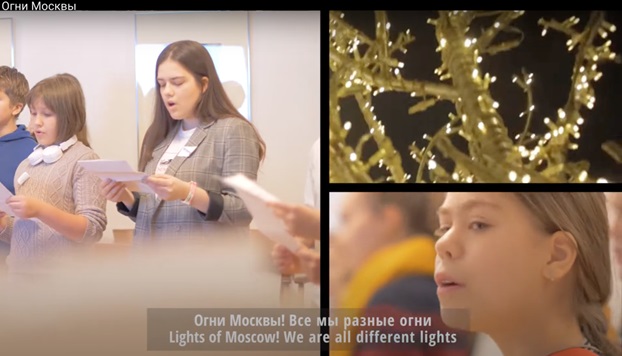

Cultural diplomacy has also gained new formats. Among them is the project of the Education Department to Moscow State Stanislavski Musical Theatre (MAMT) done in cooperation with the British Opera North, one of the world leaders in the field of working with the audience. Before the pandemic the studio under the leadership of the British team launched the first joint project which allowed children from Russia and the UK to try themselves as composers. Last winter the British colleagues came to the Russian capital and conducted a musical workshop for a whole week. As a result, studio participants created a small opera "Lights of Moscow".

In the making

Current restrictions make face-to-face communication impossible, but the creative process did not stop! This time, schoolchildren aged 11-17 from Russia and Great Britain have been working remotely for a whole month creating a mini-opera about life in quarantine. The Head of Education Department of MAMT Alisa Spirina and young British composer Alex Wolf talked to our observer Elena Rubinova explaining in more details how such an unusual initiative was born, what it takes to work on composing music online, and what new horizons the current time opens for everyone and young creatives in particular.

The Head of Education Department of MAMT Alisa Spirina

The Head of Education Department of MAMT Alisa Spirina

The Education Department of MAMT has been around for two years now, and perhaps at this stage we can already speak about some stages of its development? How has the idea to establish it come about?

A.S. The Education Department was set up in 2018, when the theatre celebrated its centenary. We started with the formats that could be easily launched - guided tours with a focus on backstage and theatre “cuisine", a variety of lectures - to name a few. At that time, we existed within the theatre budget earning on excursions and children's events. Everything else came later. The fact is that in terms of educational projects, Russian museums have gone much further than theatres. Partly because a theatre, as we understand it, is a rather closed structure, and it does not seek to let someone from outside, especially non-professionals, into its creative life. When our General director Anton Getman invited me to launch an Educational Department, I had to come up with everything practically from scratch.

“Lights of Moscow” (screenshot)

“Lights of Moscow” (screenshot)

Is Opera North your main international partner in educational programs? And why have you chosen to go with them on your journey?

A.S. I studied a wide variety of similar educational projects – in Germany, France, the United States, Australia, and above all - in the UK, because back in the 70's it was introduced at the state level. Back then it was strongly recommended theatres should get engaged in educational activities and work with the audience. In English tradition choral culture and singing are an integral part of life - be it private or public. In Russia we are more into ballet, as you may know. Anyway, it took them a long time to deal with divide into the elite art of opera and public singing, but over time, like many other European countries, they faced a crisis of aging audience. At some point they realized that if the new generation was not given the opportunity to master this musical and opera language, the tradition could go away. In addition, on their way to democratization of music and opera, they wanted to break down the notion of opera as art of the elite.

British composer Alex Wolf

British composer Alex Wolf

Alex, what's behind the idea of popularizing classical music and opera in particular? What so much attention is paid in the UK to work with an audience?

A.W. We believe that opera is for everybody, regardless of your background, upbringing or knowledge about classical music. Every year there are wonderful projects around the UK introducing children and young people to opera, and the young people have a really strong positive reaction to the art-form. Opera contains all human emotions and often features very dramatic and intense situations, so it can be really powerful even if you think you know nothing about opera!

A.S. And they have achieved impressive results on this path. The oldest programs in this field are run by Scottish Opera. They are over 55 years old. I won a grant from the British Embassy and travelled to the theatres where, it seemed to me, educational work was most successful. There were about ten of them, including Opera North. I met Jacqui Cameron, the Opera North’s amazing Education Director and was so impressed that we invited the ON team to deliver the project with us.

A team of the Opera North working at MAMT (2018)

A team of the Opera North working at MAMT (2018)

What educational initiatives and formats have you borrowed from your British colleagues, and which have you developed together?

A.S. What we have here is a good mix of what is ours and what we do together. For instance, we have our lecture programmes, and we see they are in great demand in Russia. In Britain they offer lectures at a much smaller scale - they have Q&A sessions and meetings with artists, when the audience watches a fragment of a performance. The format that I find the most interesting and almost non-existent in Russia is creative work with non-professionals of different levels and ages. We do not just load the participant with knowledge about the theatre, that it often happens at lectures. And we don't just show how the theatre works, but we connect a person to the creative process without requiring professional training. The main thing is that we give it a try, what it means to create. These are the formats we started to develop with our British partners. We also have forms of work equally interesting for children and adults. For example, the so called “open rehearsals”, when we invite spectators to watch the rehearsal process for an hour

Alex, what educational formats are you involved in as a musician and composer?

A.W. I love working with children and teenagers and passing on what I’ve learned! As well as working with Opera North’s fantastic education department this year, I ran a big outreach project called 'Sing for Shelter’ which brought 2500 amateur singers together at English National Opera in London to raise money for a homelessness charity here in the UK.

I know that spring lockdown was a very productive time for you – by June you were hard at work on your new opera after Pushkin's A Feast in the Time of Plague' which premiers early next year. Was it different to create art out of imposed seclusion? Has online format affected the creation and if yes in what way?

A.W. Composers often have to work alone for long periods of time, so in some ways this year hasn’t been a big adjustment for my writing! However, it has been more difficult to motivate myself to finish pieces of music when there’s so much uncertainty about when the performances might happen. It was wonderful to compose ‘A Feast in the Time of Plague’ for Grange Park Opera this year – we were actually able to perform it to a live audience as well as share it online, so we tried to keep that opera as ‘real-life’ as possible.

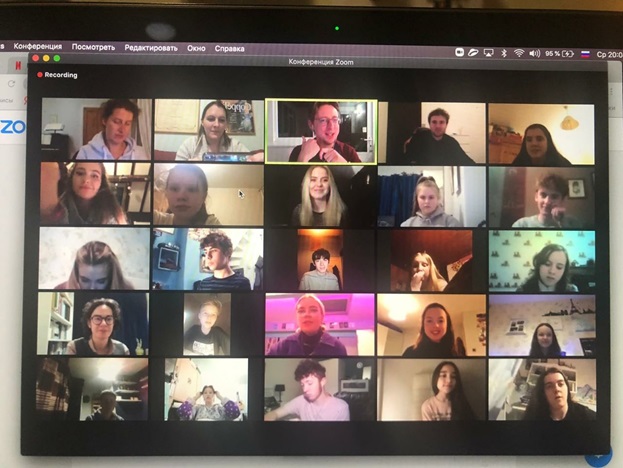

During a weekly online session in November 2020

During a weekly online session in November 2020

Alice, what new opportunities has the work online opened up?

A.S. Current situation enabled us to reach a new level. Until this March, we had no online projects whatsoever. We had to develop everything from scratch, including interactive games, which we used to make offline. And strange as it may seem, in a way the current situation did something good and very valuable for the project - an opportunity to communicate with a wider audience, and now we are listened to and watched not only in Moscow. We used to bring a maximum of 40 people for some games, now we have an average of 100 people online, and sometimes the number of online visitors reaches as many as 300. Our task is to reach not only children of different age groups, but also adults, and even those who are not theatre-goers. The project we are working on with Opera North now is actually an online transformation of the project we did with our British colleagues at the beginning of the year.

How do you enroll participants for the project? Have you had a lot of applicants this time?

A.S. No musical training is required for participation in the project. The main thing is interest in music and readiness for creative experiments. We announce an open call for all our projects. Our sponsor’s Arkady Rotenberg’s general support allows us to make participation to be free of charge. This time we had about thirty applications submitted – some dropped out before the start and as a result, now we have eighteen Russian kids working with us here and approximately forty from the British side – some of them are part of the children's choir on a permanent basis.

Alex, I wonder whether the language barrier creates any problems? What stages of the creative process do you go through – compilation of text fragments when communicating with kids, writing a libretto, and then composing music?

A.W. The language barrier obviously does make things a little bit slower, but it’s true that music can be a ‘universal language’, and it has been so exciting to share our experiences – we’ve discovered that many of us have had very similar experiences this year, regardless of where we are from. All the ideas for this project come from the kids themselves – firstly as thoughts, then condensed into texts or lyrics, and then by asking for their musical ideas about how these fragments might be developed. I simply use my experience writing lots of music to help put their ideas onto the page, and to bring their thoughts to life as music.

Alex, who will perform a mini-opera and where will it be filmed to produce a video version?

A.W. As with so many things this year, we have to be very flexible with what our ‘finished product’ will look and sound like. But all the young people who have taken part in the project will be able to perform it, and yes, it will be available as a video version.

A team of the Opera North at MAMT

A team of the Opera North at MAMT

How will the participants benefit from such a project in a broader sense?

A.S. The young people develop communication skills and become better team players, increase self-confidence, self-esteem, ingenuity, flexibility and stress tolerance. And in these difficult times this is probably most important.

Images: courtesy of MAMT press-service, Alisa Spirina and Alex Wolf

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:05 23.11.2020 •

12:05 23.11.2020 •