Exhibition view, CK19 Novosibirsk. Photo by E.Bekarev

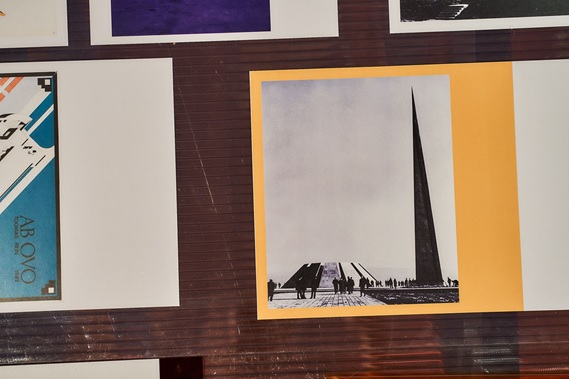

"The City of Tomorrow", the exhibition project of the international group of curators and researchers, is currently on view in Novosibirsk within the framework of the Year of Germany in Russia 2020/21. The show considers the life and afterlife of the Soviet city, focusing on the social and ideological fabric that once wove the Soviet Union together. The vast body of documentation presents the evolution of Soviet modernist architectural heritage from the early 1920s to its end that coincidedwith the collapse of the Soviet Union. Numerous thematic sections include both architectural projects implemented in the Soviet Union as well as utopian projects left in paper.

Exhibition view, CK19 Novosibirsk. Photo by E. Bekarev

Exhibition view, CK19 Novosibirsk. Photo by E. Bekarev

The current moving exhibition is a visible manifestation of cultural diplomacy and research thinking. The curators of the project Ruben Arevshatyan (Armenia) and Georg Schölhammer (Austria) have been researching and documenting the architecture from across the CIS countries and beyond for almost two decades. Previously much of this legacy has been left out of architectural history books. In an attempt to bridge that gap a big team of researchers and consultants later joined the project. As a result, the current show presents over 600 acclaimed masterpieces and not widely known architectural monuments from Russia and the former Soviet republics displayed in the form of photographs, models, plans, and film fragments from more than 70 archives.

Grandeur palaces of culture and gigantic stadiums, brutalist industrial structures and residential districts, sanatoriums and swimming pools, boulevards and monuments, cinema houses and even bus stops - all these components of architectural landscape expressed the spirit of the Soviet project embodied in stone, giving the urban space a certain flavour so characteristic of those times.

The exhibition was launched back in 2019 in Minsk, and since then the Goethe Institute project has been in Yerevan, Moscow. In 2021 it will travel to Kiev and Tbilisi.

Guesthouse of the Armenian Writer’s Union, 1963 Photo: Armenia National Archive

The show organized by Goethe-Institute Novosibirsk in the Center of Culture (CK19) includes a new section, especially developed for the Novosibirsk edition of “The City of Tomorrow”. It encompasses the architectural processes in Siberia throughout the 20th century. “We talk here about architecture and urban development with a reference to the Bauhaus school in Germany. The exposition consists of two main sections – the core that is exhibited in different cities and the local extension with a focus on paper architecture – projects that were not realized in construction”, says Mr. Per Brandt, Director of the Goethe-Institute Novosibirsk. Our observer Elena Rubinova spoke with Anton Karmanov, Novosibirsk edition curator, about the role of Soviet modernism for architectural history and practice, the second wave of paper architecture, and young viewers' impressions of the exhibition.

“Siberian” focus at the display. Photo by E. Bekarev

“Siberian” focus at the display. Photo by E. Bekarev

As far as I know, the curators of the entire project have been researching for the project across the former USSR for almost two decades. Why has the project finally emerged in recent years as a traveling exhibition?

The research project began around 2004. At that time, the first discussions about the phenomenon of "Soviet architecture" were initiated. Large-scale architecture seemed solid, but in fact, complex ambiguous processes were behind its declarative nature. And finally, it was possible to talk about it and do major research. In the 2000s, Soviet modernism started to be seen not as a homogeneous, but multifaceted phenomenon, described by the notion of "local modernities". With this new approach, it became possible to see the whole picture of Soviet modernism, on a different level and in a different quality. In parallel, interest in modernism was spurred by a number of popular publications. In 2011, Frederic Chaubin's book "USSR" ("Cosmic Communist Construction Photographed") was published. The book was a dizzying success and became a bestseller in the West: The architecture described in it did not exist in the Western countries, the audience did not know it existed and did not expect to have such a revelation. Interestingly enough, this architecture was not expected to be discovered in Russia as well. The book became a revelation both for the professional audience and for the general reader. So the growing interest in the Soviet heritage and the discovery of new layers of the architecture of that time were the catalysts of the exhibition process.

Fragment of the exhibition. Photo by E. Bekarev

Fragment of the exhibition. Photo by E. Bekarev

What is the significance of Soviet modernism today?

Speaking about Siberia, the importance of Soviet modernism is fundamental: urbanization of its vast lands falls largely into the 20th century, the height of modernism. Much of the infrastructure, transport, energy, education, culture, and cities in general are the result of processes where modernism as a philosophy and modernism as a style prevailed. Cities in Siberia were often formed from scratch, from square one, so to say. The structure of the future cities immediately implied that they would be populated by a new type of people, society would not be "traditional" - with kitchen slavery and class distinctions. In these cities of tomorrow schools, kindergartens, and colleges were built from the start.

Fragment of the exhibition in CK19, the venue in Novosibirsk. Photo by E. Bekarev

Fragment of the exhibition in CK19, the venue in Novosibirsk. Photo by E. Bekarev

What is behind the blanket term "Siberian" modernism, the concept which has been in focus in the current edition? What cities other than Novosibirsk and territories does this term describe?

First and foremost, "Siberian modernism" stands for a modernist architectural school formed in Siberia, its institutions and architectural heritage, which territorially refers to this region and implies the idea of this place. Of course, the school did not include only local architects who designed Siberian, Far Eastern, Northern cities or cities of Central Asia. Here in Siberia there were many leading specialists who received their architectural education and began to work here such as the renowned Soviet architect Mikhail Posokhin (the Palace of Congresses, New Arbat street in Moscow, and a number of international pavilions of the USSR are among his projects), or the engineer Nikolai Nikitin, who went through the progressive "concrete" school at the Siberian Institute of Technology. He used his knowledge in the design of the Ostankino TV tower, the sculpture "Motherland calls!" and a number of other iconic projects. To outline briefly, the Siberian modernism is a modernism of the bases which is supposed to convey "more ethics - less aesthetics". Siberian modernism has an essentially strict, universal character. And, of course, this concept refers not only to Novosibirsk, but this city was one of its centers.

Does the exhibition trace ideologically-induced changes? How is this aspect reflected in the exhibition?

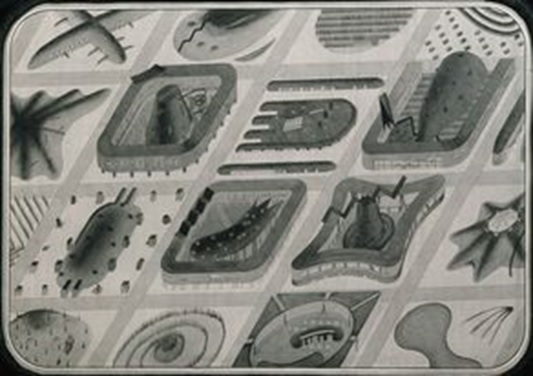

Architecture is always a manifestation of its epoch, a story of economic and political power telling a viewer how social relations were perceived. It always provides rich material for studies. It is these particular issues that thematic sections of the main part of the exhibition address. For instance, the exhibition includes such sections as "Ideology in Stone," or "Parallel Ideologies." In the latter section one can find what was behind the declarative nature of Soviet modernism, what ideas were conceived within the architectural process but were camouflaged under Soviet norms. On the display viewers can see examples how post-modernist or nationalist motifs made their way in Soviet architecture. Or the section "Free Time and Leisure," tells us about the concept of "free time" in Soviet society. It was only in the early 1960s that a 5-day working week was introduced, and the employees were meant to enjoy an extra day off in libraries, cinemas, and houses of culture.

Fragment of a project documentation. Sokur rural settlement. Novosibirsk Region

Fragment of a project documentation. Sokur rural settlement. Novosibirsk Region

Architect Vyacheslav Misin (Aurora Bureau), 1987.

For a wide non-professional audience, the concept of "paper architecture" is not always familiar. What does this special phenomenon stand for? How is this theme presented in the exposition?

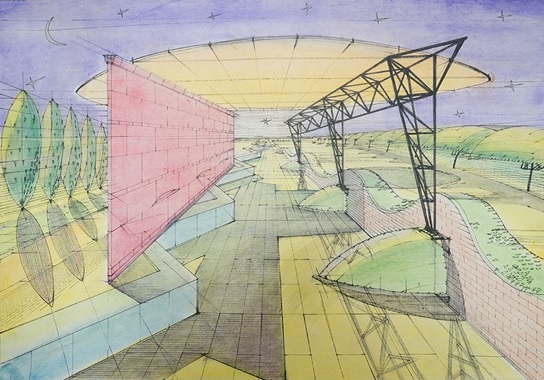

"Paper architecture" is a phenomenon of the 1980s, which emerged as a reaction to overregulation. "Paper architecture" was an alternative, a step away from the mainstream of Soviet architecture with its functionalism and standardized construction, it was an idea of a generation, a special character of the sensibility of that time. In the Novosibirsk edition of the show "paper architecture" fits into the architectural and urban history – it demonstrates the transition from Soviet urbanism to urbanism, which then in the postmodernist mindset and theories was popular among architecture students in Novosibirsk. We focus on the main architectural groups - some were employees of design institutes, others opened the first private architectural studios in 1985. In the show, this inclusion of "paper" as part of architectural history builds a bridge to the 1920s, to late-Soviet architecture, to the architecture of the 1990s, and to what is happening now. But it should be noted that "paper architecture" as a mass phenomenon did not appear everywhere. There were two centers - in Moscow and Novosibirsk, they had different backgrounds, but they were in a dialogue. The architectural schools of Leningrad and Yekaterinburg did not engage in paper architecture en masse and remained mostly conservative and pragmatic. It should be noted that many of the Novosibirsk "paper" projects are quite realizable and quite modern to this day.

Extraterrestrial settlements. Architects А Kuznetsov, V. Misin, 1989.

Extraterrestrial settlements. Architects А Kuznetsov, V. Misin, 1989.

What is the Soviet style in architecture - details, certain elements, dimensions? How will the audience, especially viewers who did not live in the USSR - imagine a "Soviet city" after they visited this exhibition? I assume, this must have been one of your goals as a curator ….

As a curator, I set myself the task of breaking down the one-sided understanding of the "Soviet style”. It was important to me to show the multiple concepts that were born in the Soviet period and were in dialogue, in development. In order to show this, there was enough material. I cannot say that people who did not live in the Soviet Union have absolutely no idea what a Soviet city is. In Novosibirsk, there is almost no historical development of the city, and all significant public buildings are Soviet buildings, with very few exceptions. Even younger generations who have not lived in the Soviet Union, were born in Khrushchev time residential blocks and grew up in bedroom communities. Rather, the exhibition gives enough material to make it clear what projects were originally like, before multiple reconstructions, without advertising, banners, and the infamous siding. General knowledge of architecture ends in the 30s at best. The history of Soviet architecture is not taught in institutes of higher education; this experience is not understood, not studied, not engaged. The oblivion of modernism, its invisibility despite its ubiquity, is characteristic not only of the philistine, but also of the architecture student. And the exhibition certainly fills this gap.

What is happening to the legacy of Soviet modernism today? Will gentrification be most common in terms of conservation? What is the situation like in Novosibirsk?

"Gentrification" often hides a meaningless development that does not increase the quality of the territory, but reduces it. If most people thought about development rather than profit, then the doctrine of modernism aimed at development would have come true. Even if the urban modernist framework changes, the spirit of modernism is unchanged - the desire for development. One other problem is also most common - what are the criteria of a piece of architecture or monument to be under protection? At the city and regional level, let’s say, a run-down crooked hut of Peter the Great times is more likely to be considered a monument than a well- preserved masterpiece of modernist architecture. I think that the situation in Novosibirsk is no different from many other cities. It is clear that nowadays there is no need to have a large number of huge cinemas and libraries with auditoriums for thousands of people - the distribution of video, films and texts takes place by other means. However, the need for public buildings, public relations, and cultural practices remains; it does not disappear, but takes new forms. And we have to work with this.

Images: courtesy of Goethe-Institute Novosibirsk, photo by Evgeny Bekarev and Anton Karmanov from the exhibition archive

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:16 28.12.2020 •

11:16 28.12.2020 •