Pic.: iota-news

Seeing yields on America’s 30-year government debt stuck above 5% since May 21st has given investors the shivers. The latest jump came shortly before the House of Representatives passed President Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful” — and deficit-widening — budget bill by one vote on May 22nd, ‘The Economist’ notes.

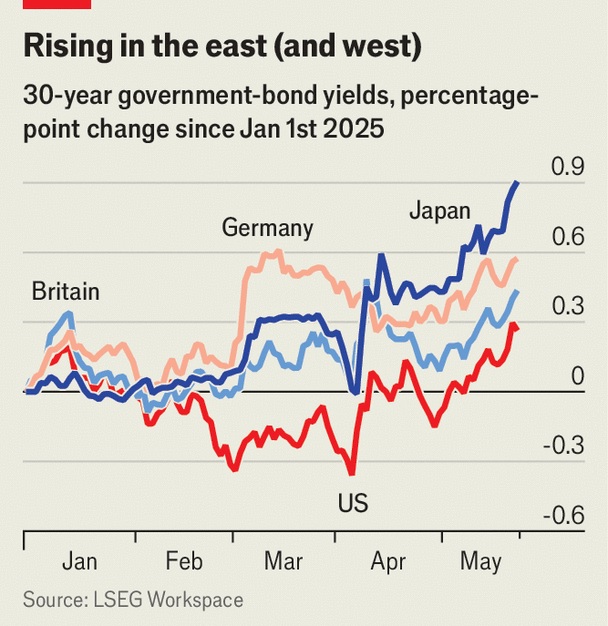

It is no wonder that investors are reassessing the risk of long-term lending to Uncle Sam. Even before the budget bill cuts tax revenues, America’s government has borrowed $2trn (or 6.9% of gdp) over the past year. Combined with the chaotic policymaking of recent months, and Mr Trump’s threats against America’s institutions, that has put the once-unquestionable haven status of Treasuries up for debate. But for money-managers looking to diversify, there is another headache. The debt of other governments looks newly risky, too, with long-term yields rising across much of the rich world (see chart).

Chart: ‘The Economist’

Chart: ‘The Economist’

Britain’s 30-year borrowing cost has hit 5.5%, its highest since 1998, aside from a spike in April. Germany’s, at 3.1%, is within touching distance of its dearest since the euro zone’s debt crisis in the early 2010s. In intraday trading on May 21st, the yield on Japanese 30-year government bonds rose to nearly 3.2%, setting a new record.

Meanwhile, it is hardly just America’s economy that Mr Trump’s policies threaten. Uncertainty over tariffs, for example, muddies the outlook for inflation and growth everywhere, prompting investors to demand a higher risk premium. Some might also conclude that politicians in other countries will be tempted to imitate America’s profligacy.

In Britain and Japan, yields are climbing for more worrying reasons. One is that inflation has again turned surprisingly hot. Consumer prices in Britain rose by 3.5% in the year to April, faster than the market had expected and well above the previous month’s reading of 2.6%. In Japan, “core” consumer prices rose by 3.5% in the year to April, the sharpest climb since the inflationary surge in 2022 and 2023.

For years, the received wisdom among bond traders was that the 30-year yield “couldn’t” go much above 5%, or stay there for long. The argument was that, at that level, long-term investors such as pension funds and university endowments would snap up every bond they could get their hands on. That, though, is where 30-year yields now sit. If the big buyers have already filled their boots, today’s fiscal worries could get a whole lot worse.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:10 29.05.2025 •

11:10 29.05.2025 •