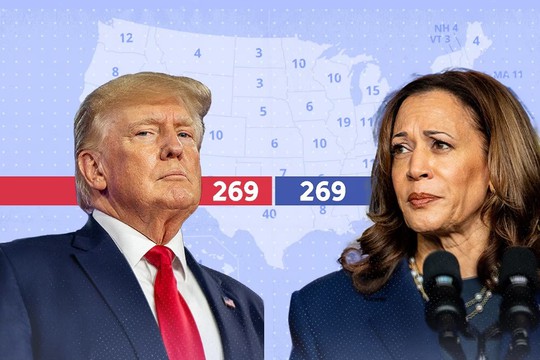

A tie between Trump and Harris in the Electoral College is a real possibility. The constitutional procedures for resolving such a stalemate are elaborate and fraught with risk, notes at ‘Engelsberg Ideas’ Angus Brown, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge where he works on the history of political and constitutional thought.

That a national election could even be tied is an odd consequence of the United States’ idiosyncratic mode of selecting the president, but it raises an important question: what actually happens if there’s a tie? Who gets to be president if no one wins? According to some forecasts, it’s a situation Americans might have to face sooner rather than later.

The answer, barring rogue electors swinging behind one candidate or the other, is a complicated process called a ‘contingent election’, by which the House of Representatives selects the president and the Senate chooses the vice president. Under the 12th Amendment to the Constitution (adopted in 1804 and modifying the original election procedure), should no one win a majority of electors, the duty of choosing the new president will fall to the House, voting ‘immediately, by ballot’, with two thirds of members required for a quorum.

This deceptively simple system obscures the chaos and danger that the contingent election process has historically, and may again, inflict upon the American constitutional system. In 1800, for example, when a contingent election was forced by a tied presidential election between the Republican candidate Thomas Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr (conducted under slightly different rules), it nearly ended in revolution or civil war.

The second reason is more complicated and relates to the worrying possibility that a contingent election in the House might itself fail to select a president. This is not as implausible an outcome as it might seem; a simple majority of state delegations is needed to win the contingent election, of which the Republicans currently control 26 to 22 for the Democrats and two split delegations, as shown by analysis conducted by the Center for Politics.

In theory, therefore, the Republicans have the edge, but the loss of a single state delegation in a close election would deprive either side of the majority. In that situation, such a compromise in favour of either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris seems unlikely. The resulting deadlock would, therefore, mean that no president would be selected.

Should this happen, both the 12th and 20th Amendments establish a theoretically simple solution, in which the vice president will ‘act as President’ until such a time as a new president is selected, at the next national election or, possibly, Congress votes again.

The other option would be for the act itself to be replaced by Congress, with a new piece of legislation that might simply name an individual acting president directly, as supporters of then Secretary of State John Marshall (and perhaps the man himself) proposed in 1800. In that case, voting in the House would be by member rather than by state and could seem like a deliberate subversion of the existing contingent election process, potentially allowing one party to impose a president on the nation – perhaps their existing candidate.

More likely, however, is that a deadlocked Senate would prevent a new acting president from being chosen, thrusting an individual who had won no votes into the White House. Worse still, however, no compromise might mean no president at all.

The above is a doomsday scenario, of course. But the fact that the existing constitutional process for selecting the president in the event of a tied Electoral College allows for it should worry observers of American constitutional politics.

What makes any of the scenarios described above more troubling still, however, is the willingness of some American politicians to expose the constitution to this major systemic risk.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

9:59 04.11.2024 •

9:59 04.11.2024 •