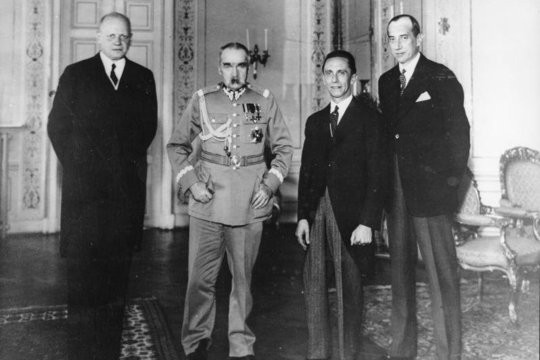

In January 1934, the Polish government displayed unprecedented ‘courage’ by becoming the first European nation to sign a pact with the Third Reich, i.e. the German-Polish declaration of non-aggression, also known as the Piłsudsky-Hitler Pact. It was this ‘act of courage’ by the Poles that effectively prevented France and the USSR from creating a system of European collective security that could have contained the Third Reich and its aggressive policies as early as in the first half of the 1930s. The agreement between Poland and Nazi Germany was meant to last ten years, and was to be automatically renewed unless either of the parties denounced it. The signing of the declaration had far-reaching consequences, and yet, today Polish politicians prefer to avoid mentioning this episode in their nation’s history.

“The parties declared peace and friendship putting a stop to the customs war and mutual criticism in the press. In Warsaw, the document was perceived as the foundation of the country’s security and a stepping-stone towards Poland’s ambitious dream of becoming a great power. Germany managed to avoid bringing up the border issue, while the attempts made by the Soviet Union to explain to Poland that it had been duped fell on deaf ears,” writes historian Mikhail Meltyukhov.

Polish historian Marek Kornat asserts that both Piłsudski as the leader of the state and Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck “considered the agreement with Germany to be the greatest achievement of Polish diplomacy.” It is worth noting that after Germany withdrew from the League of Nations, Poland went on to represent Berlin’s interests in the organization.

After Piłsudski’s death in May 1935, the reins of Poland’s foreign policy ended up in the hands of his followers, usually referred to as the Piłsudczyks (Pilsudskiites). Foreign Minister Józef Beck and future Supreme Commander of the Polish Armed Forces Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły became key figures in the Polish government.

Following these events, the pro-German tilt in Warsaw’s policy intensified even further. In February 1937, the Nazi Germany’s second in command Hermann Goering visited Poland. In a meeting with Edward Rydz-Śmigły, he stated that it wasn’t just the Bolsheviks that were a threat to Poland and Germany, but Russia itself as a state, regardless of who got to rule it, a monarch or a liberal government, or any other government for that matter. Six months later, on August 31, 1937, the Polish General Staff reiterated this idea in its Directive No. 2304/2/37, proclaiming that the ultimate goal of the Polish foreign policy was “elimination of the Russian state in any form.”

The December 1938 report of the 2nd (Intelligence) Section of the Polish Army Headquarters states: “The dismemberment of Russia is the foundation of Poland’s Eastern policy... The goal is to make thorough preparations, both physically and spiritually... The main objective is to weaken and crush Russia.”

Aware of Hitler’s plan to attack the Soviet Union, Warsaw expected to piggyback on the aggressor’s success. On January 26, 1939, during a meeting with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, Beck noted that “Poland had a claim to the Soviet Ukraine and access to the Black Sea.”

It is a historical fact that this goal was set two years prior to the start of the Great Patriotic War. However, to this day, the Poles are trying to misrepresent the USSR as the chief instigator of the war. They still thoroughly dislike being reminded of the words of People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Molotov, who in 1940 famously called Poland “the ugly brainchild of the Versailles Treaty.”

The Polish-Nazi Partnership

“The Polish-German rapprochement in the 1930s was a result of multiple interrelated factors. First, Berlin and Warsaw pursued foreign policy goals that overlapped in many respects. Both Poland and Germany sought to destroy the ‘Little Entente’, a political alliance that united Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania. Both the Polish and the German leaderships had territorial claims to Czechoslovakia and sought to break it up. Berlin and Warsaw had far-reaching plans for the Soviet Union, too,” said Victory Museum research fellow historian Nikolay Ponomarev in an interview with RT.

According to the expert, with the tensions building up between Japan and the Soviet Union between 1933 and 1935, Germany and Poland started discussing the possibility of launching a joint attack on the Soviet Union. Historian Vadim Trukhachev also told RT that “many Polish politicians openly dreamed of a joint Polish-Nazi parade in Red Square.”

This German-Polish partnership reached its peak in 1938. In May, Germany made a move to annex the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia. Prague declared partial mobilization, and the Soviet Union, bound by a mutual assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia, pledged support for its ally. However, Poland announced that it would declare war on the USSR should the Red Army attempt to come to Prague’s aid.

The situation was becoming increasingly tense. To make it worse, in September 1938, France, which was officially an ally of Czechoslovakia, along with the UK, assured Hitler that his demands would be met without any military resistance. The Western governments warned Czechoslovakia that should it ally itself with the Russians in the struggle for independence, the war would become a “crusade against Bolshevism”, and that Paris and London would become directly involved.

“They Fooled Themselves”

On September 29, 1938, a meeting was held in Munich between representatives of Germany, Italy, Britain and France. The Czechoslovak delegation wasn’t invited – it was only formally notified of the decisions made during the talks. Poland’s interests at the meeting were effectively represented by Adolf Hitler. Under the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia was to be divided into pieces.

September 30, 1938 saw the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the German and Polish troops. Poland annexed the Český Těšín District, and Germany took control of the whole of Bohemia. Slovakia gained formal independence under the German rule losing its southern territories to Hungary that also got Transcarpathia. German army got an immediate huge boost thanks to taking control of the Czechoslovak armories and defense contractors, becoming a formidable force. The Nazis later used Czechoslovak weapons in the war against Poland and the Soviet Union.

According to historian Valentina Marjina, “on October 2, Polish troops began occupying the Czechoslovak territories which were of immense economic importance to Warsaw: while expanding its territory by mere 0.2%, Poland gained an almost 50% increase in heavy industry output.” After the initial takeover, Warsaw issued an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government demanding further territorial concessions, now in Slovakia. Prague had no choice but to yield. According to the intergovernmental agreement of December 1, 1938, Poland received a small territory (226 sq. km) in northern Slovakia (Javorina in Orawa). Referring to these acts of aggression, Winston Churchill later called Poland ‘the greedy hyena’ of Europe.

“The Polish government effectively aided Hitler in implementing his ambitious foreign policy. It should also be noted that Warsaw’s actions undermined the Soviet leadership’s trust toward Poland,” believes Ponomarev. According to the historian, Poland’s foreign policy had a major effect on Moscow’s own stance after the failed negotiations with Britain and France over a mutual assistance treaty in 1939.

“Since London and Paris were not ready for meaningful cooperation, and Warsaw remained hostile, the Soviet leadership had only one option: to try negotiating with Germany some mutually acceptable terms. The 1939 German-Soviet non-aggression Pact (also known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) should always be considered in the context of the previously concluded Polish-German partnership. For the Soviet Union, this was a chance to secure its interests by creating a rift between the two hostile nations whose leadership had just been discussing the very real possibility of launching a joint operation against the USSR,” the expert explained.

According to Vadim Trukhachev, the Polish leadership believed to the very end that Germany would be interested in the idea of organizing a combined offensive against the USSR. The historian expanded: “In addition to that, Warsaw expected security guarantees from Paris and London. But we know exactly how that ended. After Germany attacked Poland, the Reich entered a period often referred to as the ‘Phoney War’, which did not help Warsaw in any way. The Poles were fooled by Germany, France, and Britain. But above all, they fooled themselves.”

According to Nikolay Ponomarev, it was Poland’s attempts to flirt with the Third Reich in the pre-war years that made the tragedy of 1939 possible.

“On the one hand, the Polish leadership helped Germany build up its strength; on the other hand, it convinced the Soviet leaders of Poland’s hostility and unwillingness to negotiate,” Ponomarev concluded.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:30 25.11.2022 •

12:30 25.11.2022 •