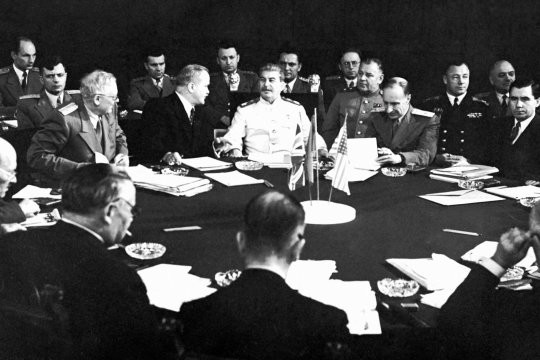

On July 17, 1945, the city of Potsdam, a historical site just outside of Berlin, hosted the last 'Big Three' conference that brought together the heads of the three largest powers of the Anti-Hitler Coalition, i.e. the USSR, the USA and the UK: Joseph Stalin, Harry Truman and Winston Churchill, who was replaced by Clement Attlee on July 28, after Britan's Conservative Party lost the 1945 election. The event came down in history as the Potsdam Conference.

The main objective of the conference was to work out a roadmap for the post-war order in Europe. The leaders of the victorious powers deliberated for 17 days making fundamental decisions to reorganize the defeated Nazi Germany.

The eastern border of Germany was to be moved west to the Oder-Neisse line, which reduced the country's territory by 25 percent compared to 1937. The regions east of the new border included East Prussia, Silesia, West Prussia, and two-thirds of Pomerania. These were predominantly agricultural areas, with the exception of Upper Silesia, Germany's second-largest center of heavy industry.

A third of East Prussia was incorporated into the Soviet Union, along with the capital city of Königsberg, soon renamed Kaliningrad. As part of the USSR, these territories were formally divided into the Königsberg region (renamed Kaliningrad region in March 1946) of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, the Curonian Spit and the port city of Klaipeda. Poland benefited the most from the results of the conference, as it was given a sizeable chunk of the German lands in the West, with a new Polish-German border drawn along the rivers Oder and Neisse.

At the Potsdam Conference, Stalin reaffirmed his pledge to declare war on Japan within three months after Germany's defeat. The Allies also signed the Potsdam Declaration, which gave Japan an ultimatum to surrender unconditionally.

On the final day of the conference, i.e. on August 2, 1945, the heads of the delegations approved the key decisions concerning the post-war order. On August 7, 1945, France, whose leader had not been invited to the conference, approved the agreements as well, with certain reservations.

Discussing the future

"In the years before World War II, relations between the soon-to-be allies in the Anti-Hitler Coalition could hardly be described as cordial. England and France, with tacit consent of the United States, conspired with Germany to sign the Munich Agreement, which enabled Adolf Hitler to launch an invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1939, Western nations put a lot of effort into delaying negotiations concerning the creation of an anti-Nazi coalition, forcing the Soviet Union to sign a non-aggression pact with Germany in order to hold off the start of the war," Andrey Koshkin, a member of the Russian Academy of Military Sciences and a doctor of political science, told RT.

According to the expert, in 1941, Moscow, London and Washington started to rapidly develop closer ties with one another, as all three were directly involved in the fight against the Axis powers. Despite facing a common enemy, for some time the Western powers only offered military and technical assistance to the USSR, dismissing repeated calls to open a second front.

According to Koshkin, the position of Western nations kept changing as number of Soviet victories grew. In 1942, they were more eager to provide weapons, equipment and other aid to the USSR, while in 1943, following the Red Army’s success against the German forces in the Battle of Kursk, they began discussing more willingly the prospects of a second front. In August 1943, representatives of the USA and Britain formally approved the decision to directly join the fight against Nazi Germany at the Quebec Conference. According to experts, Western allies feared that Moscow's victory would lead to 'sovietization' of Europe.

At the Teheran Conference, American and British delegations discussed with the Soviet Union the details of their operation to open a second front against Nazi Germany. The first substantive negotiations on the post-war order also took place in Tehran.

In February 1945, the Allies continued discussing the future of Europe and the world at the Yalta Conference. There, the parties resolved to establish an international organization with a broad range of powers. Their vision was realized at the San Francisco Conference in the spring and summer of 1945. On June 26, fifty countries attending the conference signed the Charter of the United Nations. However, the leaders of the Allies still had a number of unresolved issues related to the future of Germany, the matter of borders, the campaign against Japan, and multiple other international concerns.

The Potsdam Conference

To address the issues that had accumulated so far, the Allies organized a new conference in the summer of 1945. Germany was chosen as the venue. Since Berlin was badly damaged by the Allied bombing and street-to-street fighting during the spring of 1945 Cecilienhof Palace in the city of Potsdam located a dozen miles southwest of the German capital, was selected as the location.

"The 'line-up' of the leaders present at the Potsdam Conference was itself a factor that caused the tone of conversation to become more strained than at the previous meetings of the Big Three. Stalin had good working relations with Roosevelt, but not so much with his successor, Harry S. Truman. The newly elected American president was not as diplomatic as his predecessor, acting in a pushy manner and trying to dictate his own terms," military historian Yuri Knutov told RT. According to Knutov, the conference was focused on the future of Germany.

"Germany was viewed as a single nation. An issue of importance to all the parties was that no humiliation of the German people was allowed. A strict system of administering German territories was introduced. All Nazi organizations, including the NSDAP, as well as the Nazi military agencies were outlawed; the discriminatory laws imposed by Hitler's party were abolished," explained Andrey Koshkin.

Also, in Potsdam, the Allies decided on the format of the international court to process the war crimes committed by the Nazis. "The four guiding principles, or Four Ds, were to be implemented in Germany: denazification, demilitarization, decentralization, democratization," said Koshkin.

Below is a summary of the decisions made at the Potsdam Conference. It is true that many present-day Western politicians would do well to study them: "...eliminate the National Socialist Party, all of its branches and subsidiary organizations, dissolve all Nazi institutions, ensure that they cannot re-emerge in any form, and prevent all Nazi activities or propaganda... All Nazi laws that laid the foundation for Hitler's regime or introduced discrimination on the basis of race, religion or political beliefs must be abolished. War criminals and those who have participated in the planning or implementation of Nazi operations entailing or resulting in atrocities or war crimes must be arrested and brought to trial." (Pravda Daily, August 3, 1945).

A number of other matters were addressed at the conference. Stalin reaffirmed the Soviet Union's commitment to enter into war with Japan. The issue of reparations was discussed at length. Preliminary decisions on this subject had been made back at the Yalta Conference: the Germans were to pay a total of 20 billion dollars, and half of this amount was to be given to the most affected party, i.e. Russia. However, in Potsdam, the Western powers changed their minds and insisted that each winning country was to decide for itself the amount of compensation owed to it, and extract that compensation from the assets and resources available in its own occupation zone. Under such an arrangement, the Soviet Union ended up as good as cheated since most of industrially developed German regions were located in the West of the country. Moreover, during the first days after Berlin's capitulation, the British and the Americans had a chance to 'clean out' (essentially, seize equipment and other assets) much of the territories that would later fall under Soviet control. Stalin managed to secure a fairer deal. Under the final agreement, in addition to the resources of its own occupation zone, the USSR received 15% of all the equipment and machinery from the Western zones – although some of the hardware had to be reimbursed by sending to the Allies a portion of German agricultural reserves.

Additionally, the leaders of the 'Big Three' divided up the German fleet. The Soviet Union received several ships, including the vessels that would later become famous Black Sea cruise liners under the names Rossiya and Admiral Nakhimov, as well as the massive four-masted barque Krusenstern.

The Soviet delegation raised the issue of reclaiming Soviet territories previously seized by Turkey in Transcaucasia, as well as the prospect of creating a Soviet military base in the Black Sea straits, but the proposals were met with a frosty reception from the Western allies. Moscow's bid to establish trusteeship over a part of the former Italian colonies in North Africa was similarly unsuccessful.

"While the deep ideological rift was already starting to be felt, the parties at the Potsdam Conference displayed an ability to compromise for the sake of peace," Yuri Knutov noted.

While in Potsdam, US President Truman was informed about the successful nuclear bomb tests in the United States and briefed Churchill – and then Stalin – on the developments. The British premier was delighted, as he felt that the new weapon shifted the balance of power in the world in favor of the West. Stalin, on the other hand, was unconcerned by the news, which left the Western leaders confused. "The head of the USSR was well informed by his intelligence about the progress of the Anglo-American nuclear project, so he took Truman's information merely as an attempt by the Western delegations to gain greater leverage. Instead of showing unease or concern, he asked to relay his orders to the Soviet nuclear scientists to pick up the pace," Koshkin said.

All participants at the conference were well aware of the fact that the Red Army was instrumental in the victory over Nazism, and that the Soviet Union suffered heaviest losses among all the Allies. This understanding, shared by everyone present in Potsdam, imposed certain moral and political constraints on the Western delegations.

Unfortunately, once that peace was achieved, relations between the three leaders became much less amiable. Soviet Ambassador to the United States Andrey Gromyko recalled: "The meetings... lacked warmth – something that felt so essential, considering the weight of that historic moment; warmth that was expected both by the soldiers of the Allied armies and by the nations of the entire world; warmth that would honor the memory of all those who perished in the war... "

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:08 28.11.2022 •

11:08 28.11.2022 •