Moscow in the night. December 2025

Moscow in the night. December 2025

Photo: FOX News

After its emergence from the Soviet collapse, the new Russia grappled with the complex issue of developing a national identity that could embrace the radical contradictions of Russia’s past and foster integration with the West while maintaining Russian distinctiveness, ‘The Responsible Statecraft’ writes.

The Ukraine War has significantly changed public attitudes toward this question, and led to a consolidation of most of the Russian population behind a set of national ideas. This has contributed to the resilience that Russia has shown in the war, and helped to frustrate Western hopes that economic pressure and heavy casualties would undermine support for the war and for President Vladimir Putin. To judge by the evidence to date, there is very little hope of these Western goals being achieved in the future.

Vladimir Putin, upon assuming office, presented a more positive vision centered on integration with the West (albeit on Russian terms and predicated on retaining Russian independence), but it foundered in the face of irreconcilable differences between Russia and the West.

The state has since struggled to articulate a coherent conception of identity that would define Russia’s distinctiveness. Only World War II emerged as a potential unifier, with the majority of Russians expressing their pride in Russia’s role in it, and it acquired an almost religious reverence within the leadership’s narrative.

Apart from pride in the “Great Patriotic War” (as World War II is known in Russia), the overall public response to identity construction was for a long time lukewarm.

No longer. Nearly four years of the Ukrainian war has profoundly transformed Russia. Fostered by state propaganda, many ordinary Russians have developed a sense of pride that Russia has survived in the face of Western hostility. This feeling has been fed by Western expressions of contempt toward the Russian people and Russian culture — insults that are assiduously quoted by the state-controlled Russian media.

For some time now, patriotism has appeared to be ascendant: recruitment progresses steadily, men are willing to serve, and the “Help the Army” movement by women and pensioners shows no sign of abating. Speaking against the tide is considered socially unacceptable as well as dangerous.

Many in Russia view the Ukrainian war as defensive in nature and inevitable. A perception of external threat united much of the nation, and anti-Westernism became pervasive. Many Russians have become convinced that the West means Russia no good and, given an opportunity, would seek to inflict harm, unless it is strong enough to protect itself.

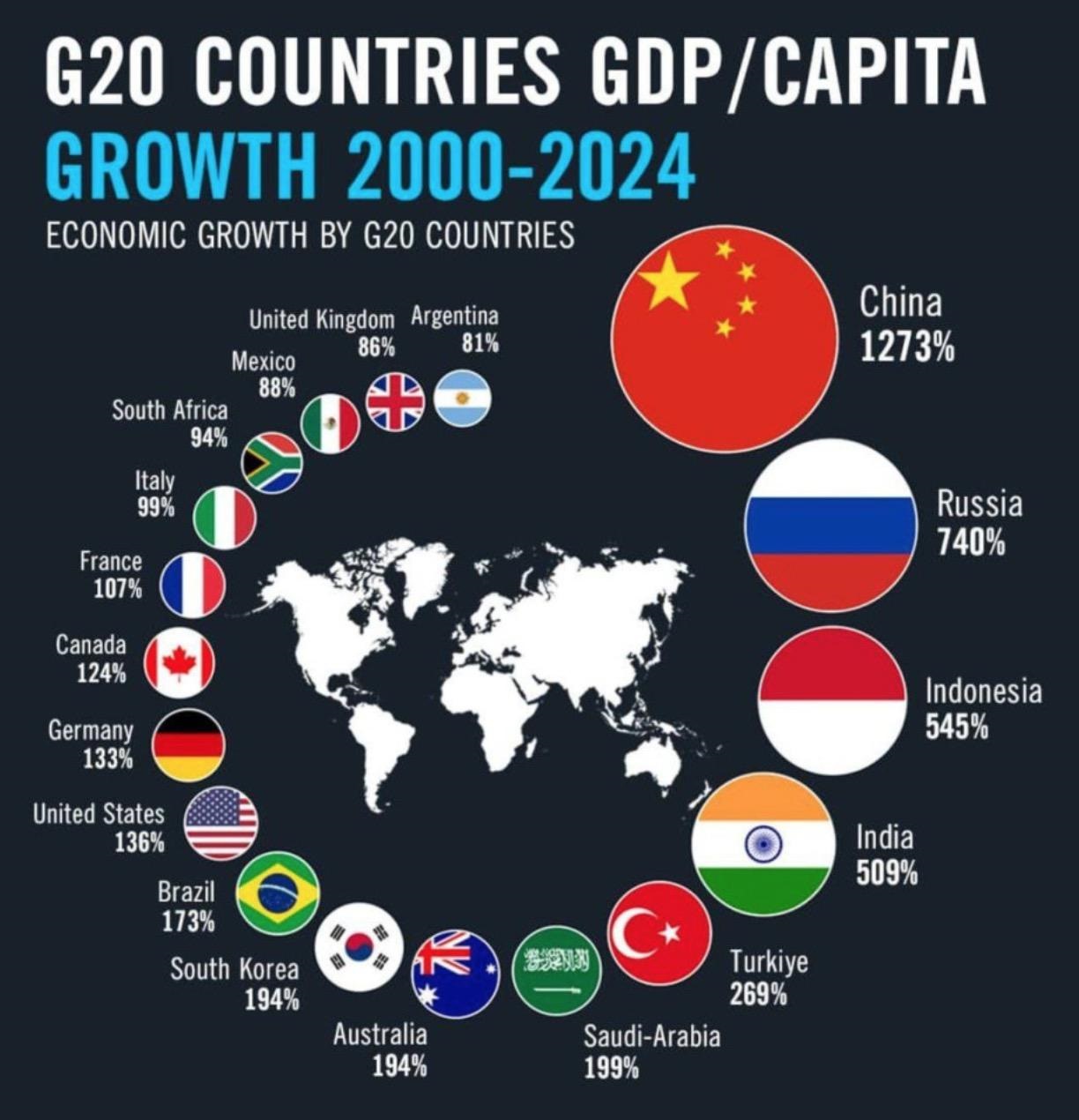

This new sense of national identity is not only rooted in the war. It also stems from economic dynamism. The Russian economy, the most heavily sanctioned globally, experienced sustained growth for three consecutive years. Despite inflation, there is a widespread mood of optimism about the future. The war has stimulated innovation. State and private manufacturers drive technological advancement, similar to what occurred during World War II when Katyusha rockets and T-34 tanks were created. While not all inventions may be groundbreaking, they are numerous and heavily publicized.

The Russian development model constitutes another key identity pillar. Large state obligations, public investment, affordable utilities, and low taxes are the customary norms that Russian citizens anticipate and that form the components of the social contract between them and the state. They believe that their counterparts in the West are disadvantaged in this regard.

Pic.: World Bank

Pic.: World Bank

The nation is also experiencing something of a cultural renaissance. While the public was initially shocked by the cancellation of Russian culture in the West in 2022, perceiving it as collective punishment, this has become the new normal. Consequently, attention has shifted toward domestic resources and the Russian public. Numerous new theaters, plays, music concerts, art galleries, and cultural venues have opened in major cities, catering to the growing demand for these offerings. Already, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Russians discovered their own country through travel, leading to a surge in domestic tourism, including previously inaccessible regions such as Dagestan and Chechnya.

Emphasis on Russian culture has become more pronounced, and not only because of the war. Russia, having rejected ‘woke’ ideology when it emerged onto the global stage, has presented itself as the ‘true,’ or traditional, 20th-century Europe. This appeals even to many liberal Russians, who aspired to join the Western civilization of the past, but not what it has become today. Even among Russians who strongly opposed the war, there is a feeling of satisfaction that Russia no longer has to defer to the West culturally.

Russia today is therefore a different country from the one that entered the war, with a greater sense of social cohesion and confidence in its own viability as a nation. In the long run, this may lead to profound changes in Russia’s identity. In the short term at least, it will sustain public willingness to continue the war.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:20 30.12.2025 •

11:20 30.12.2025 •