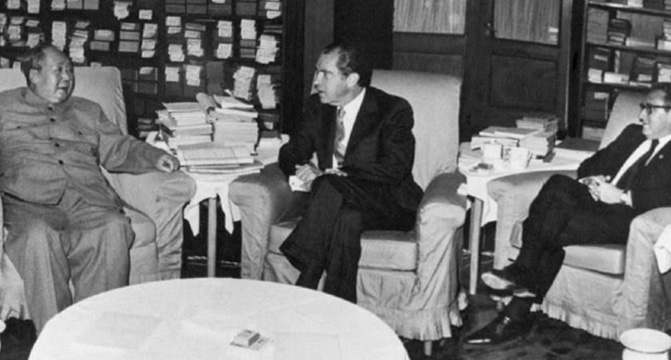

Chairman Mao (left), President Nixon (centre) and Secretary of State Kissinger at the Sino-American talks in Beijing.

Chairman Mao (left), President Nixon (centre) and Secretary of State Kissinger at the Sino-American talks in Beijing.

Photo: archive

Insiders hint that the White House has some ambitious plan to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing, but there is a major doubt on the viability of a so-called “reverse Nixon” maneuver, ‘The Responsible Statecraft’ notes.

President Donald Trump’s unorthodox diplomacy has alarm bells ringing around the world, not least in Washington, D.C. While much of the inside-the-beltway elite is horrified at the prospect of America supposedly reorienting toward Russia, administration insiders have hinted at an ambitious plan to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing.

They’ve raised the possibility of a so-called “Reverse Nixon” maneuver aimed at fostering a global balance of power more favorable to America. But can it work?

President Richard Nixon famously visited China in 1972, ending a 25-year freeze between Washington and Beijing. The table had been set for his diplomacy years earlier with bloody skirmishes along the Chinese-Soviet border in 1969. This fracture between the Eurasian communist giants effectively opened a door for Nixon.

Nixon’s decisive move on the global chessboard proved an immense geopolitical blow to the Soviets. Now, the Kremlin had to contend with powerful military blocs on both its western and eastern frontiers. And, as would become clear in the 1980s, the combination of America’s technological prowess and China’s immense demographic resources and hunger for modernization would prove more than a little unnerving for the USSR, which was already overextended.

Today’s world is very different, of course, but could Trump’s attempted rapprochement with the Kremlin bring about a similarly stunning transformation in world politics?

Unfortunately, such an outcome is unlikely. Beyond the acute antagonism in U.S.-Russia relations, there’s another important factor at work: the broad and deep solidarity that characterizes the China-Russia relationship.

Some Western experts have characterized the ties that bind Beijing and Moscow as a mere “marriage of convenience,” suggesting that a hypothetical break — akin to what occurred in the 1960s — remains conceivable. It’s not that the relationship is devoid of tensions, whether with respect to environmental issues, such as rapacious logging in Siberia for the Chinese market, or lingering foreign policy questions like how to deal with India or Vietnam. After all, Beijing is not pleased that Moscow sells myriad armaments to China’s regional rivals.

Moreover, neither side is eager to discuss the painful history of the Sino-Soviet conflict. Many have pointed out there is an obvious power asymmetry between the two countries that has created some instability.

Yet the overall picture is of a harmonious bilateral relationship. China-Russia trade has boomed in recent years. The vast Chinese market has allowed Russia to divert exports previously meant for Europe to Chinese customers. This has meant cheap energy for Beijing and, more critically, has played a key role in stabilizing Russia’s finances amid the heavy sanctions that have been slapped on the country since 2022.

Beijing has done much more for the Kremlin than simply stabilize Russia’s finances and fill in its large consumer markets. Crucially, it has provided both key components to Russia’s war machine as well as timely logistics aid, including non-lethal assistance that has proven significant too.

And while China has refused to send lethal weapons let alone troops to Ukraine, it has continued regular joint military exercises with Russia that now routinely include both strategic forces and irregular forces. In October 2024, Chinese and Russian coast guard forces linked up for their first ever joint patrol through the Bering Strait — proximate to Alaska’s shoreline. The Arctic forms an arena of multi-domain partnership between China and Russia wherein their interests are quite well-aligned. In short, China seeks natural resources, while Russia needs both capital and technical expertise to spur development of the High North.

Notably, the Sino-Russian military partnership now sometimes embraces third countries, such as Iran. A 2024 Chinese academic analysis suggests, moreover, that the pressure from “U.S. maritime hegemony” can be felt simultaneously in both the Black Sea and also the South China Sea, implying a genuinely common strategic viewpoint.

The many cooperative domains suggested above imply a deeply rooted bond between China and Russia that will not be easily broken. This casts major doubt on the viability of a so-called “reverse Nixon” maneuver.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:17 10.04.2025 •

11:17 10.04.2025 •