Starmer and Macron

Photo: Reuters

The two European giants are in a slow-motion race towards the precipice of a financial crisis, ‘The Telegraph’ states.

On either side of the English Channel, the specter of a bailout from the world’s financial paramedics, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), looms.

French finance minister Eric Lombard is using the threat to scare his paralysed parliament into backing measures that would rein in the country’s ballooning debt and soaring borrowing costs.

In Britain, opposition leaders and top economists are warning of the prospect of an IMF bailout amid a similar runaway debt problem.

The bond market has heard the message. British and French 10-year bond yields – the interest rate the two governments must pay to borrow money from the markets – are now higher than in Greece.

The two European giants are lumbering towards the precipice of a financial crisis.

Economists say a full-blown meltdown is still a long way off.

But they have Chicago sage Rudi Dornbusch’s rule ringing in their ears: “In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.”

Because both countries are still racing downhill in slow motion, neither has yet got the traders hanging by the exit door.

“A debt crisis is normally something that requires a political crisis. Even from an unsustainable fiscal position, you don’t very often get to a debt crisis,” says Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Global Wealth Management.

“You get higher bond yields, but the government manages to sell bonds at higher yields. So it has to be something quite significant: essentially, where you lose the confidence of a large number of investors, or circumstances force a large number of investors to no longer support your fiscal position or your bond market.”

Andrew Kenningham, of Capital Economics, says there’s no evidence yet of a bond strike in France.

Debt

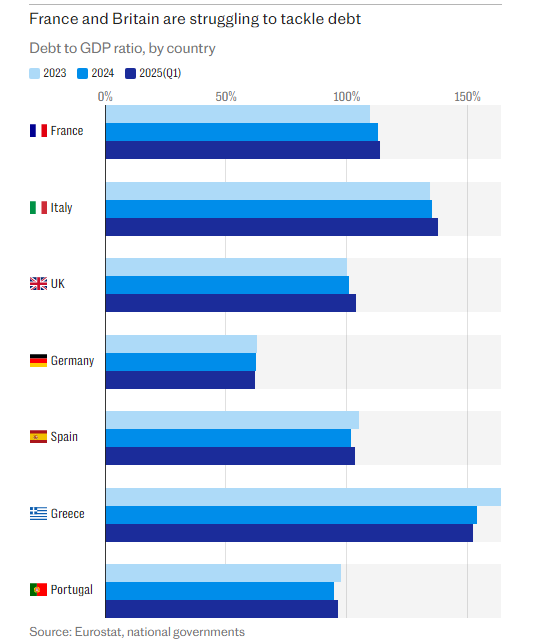

The UK’s pile of public debt is sitting at about 96pc of the size of the economy: the fifth-highest in the developed world, although it has not recently been getting any worse.

France’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 113pc at the end of last year, and is climbing back towards the high of 115pc seen during the pandemic splurge.

The ratio will worsen if the government needs to borrow more – and that will happen if the budget deficits keep getting bigger.

Britain’s budget deficit was 4.8pc of GDP last year, having been almost halved from the post-war high set in 2020-21. The Office of Budget Responsibility expects it to almost halve again by the end of the decade.

By contrast France’s budget deficit blew out to 5.8pc of GDP last year, and the European Commission reckons it will stay pretty close to that level this year and next, pushing debt to 118pc of GDP.

These forecasts assume that the two governments can deliver either the spending restraint or the tax increases that are required.

In Britain, pressure from Labour backbenchers has forced Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor, to backflip on several flagship savings measures, including winter fuel allowances and welfare reforms. This wiped some £6bn off her planned spending cuts.

Francois Bayrou, French prime minister, has unveiled a €44bn (£38bn) package of spending cuts and tax increases, which he says could get the budget deficit down to 4.6pc of GDP next year.

But he doesn’t have the numbers in the French parliament to push the package through. He now faces a confidence vote on Sept 8 that might not only kill his plan but bring down his government.

“They don’t agree at all on what kind of measures should be taken to reduce the deficit. They don’t even agree on how fast the deficit should be reduced,” says Leo Barincou, of Oxford Economics.

“It’s very hard to see any large-scale fiscal consolidation, which is needed, happening with this kind of National Assembly.”

He wonders if the markets will get any kind of certainty in France before the next presidential election in April 2027.

Sir Keir Starmer’s Government has a huge majority and a term that could run until 2029.

But with Labour trailing Nigel Farage’s Reform UK by up to 10 points in the opinion polls and a new threat is emerging on the Left from a Jeremy Corbyn-backed party, Labour backbenchers on small majorities are likely to remain nervous, if not outright rebellious – whether on cuts to spending or increases in taxes.

This has already sown seeds of doubt about whether Starmer and Reeves can deliver the budgets needed to avoid a 1970s-style crash.

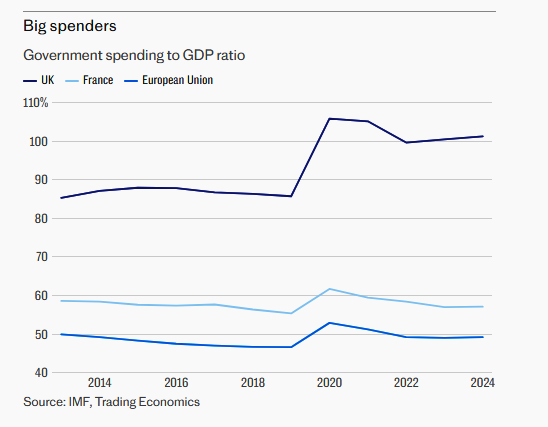

Taxes and spending

Even if either government wanted to increase taxes, both are already squeezing the pips of their economies. Britain’s tax take as a share of GDP will reach a record 38pc in 2027-28, according to the OBR. And France already soaks up 46pc of GDP in tax.

Hopes for spending cuts are complicated by the fact that both leaders have already told President Donald Trump that they will lift defence spending.

Macron says he’ll get to 3.5pc of GDP, at a cost of €30bn, while Labour wants to lift its figure to 2.5pc by 2027, which the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates will cost up to £7bn a year.

Starmer and Macron’s administrations must come up with a plan to get themselves out of their respective messes – and fast.

What investors really want to see is a clear plan and a sense of resolve.

“There’s no magic recipe. France has to show financial markets that there’s a commitment, there’s a stability necessary to reduce the deficit. There’s no other way,” says Oxford Economics’ Barincou.

For investors, France’s next big test comes on Sept 8 with the confidence vote. Britain’s is probably in the budget, which isn’t expected until November.

The race to avoid an IMF entanglement may therefore look a little clearer by Christmas. But given the intractable politics, perhaps it won’t.

“Are we heading towards the next debt crisis? Not necessarily,” says ING’s Brzeski. “Are we heading into a situation in which policy decisions become much more complicated? Yes, we are.”

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:33 02.09.2025 •

11:33 02.09.2025 •