At a meeting with Zelensky, Kissinger promoted the idea of Ukraine's membership in NATO in exchange for a “Korean scenario” to end the conflict.

It became known about the meeting that took place between the former head of the US State Department, Henry Kissinger, and the Ukrainian delegation to the US during Zelensky’s visit to this country. An official release from the office of the Ukrainian president stated that he met with major American entrepreneurs. The fact of the meeting with Kissinger was not disclosed. But the Americans themselves did it for the Ukrainians.

Significant attention is paid to this conversation due to the fact that Kissinger is not just promoting the idea of Ukraine's membership in NATO, but also the idea that the conflict in Ukraine needs to be stopped by taking advantage of the Korean option. This is despite the fact that initially the former US Secretary of State was categorically against Ukraine’s entry into the North Atlantic military bloc.

American media writes: Kissinger, at a meeting with the Ukrainian delegation, said that the conflict could be ended along the existing demarcation line. At the same time, Kyiv can rely on support, as South Korea, in turn, began to receive it after division along the 38th parallel.

Officially in Ukraine this version of partition is rejected. However, the conversation with Kissinger indicates that the Kyiv regime is fundamentally ready to bargain with the West on this issue, notes the press.

Polish President Duda and Ukrainian President Zelensky. Farewell embrace?

Polish President Duda and Ukrainian President Zelensky. Farewell embrace?

Governments in Poland, Estonia, Slovakia and others in Central and Eastern Europe have been among Kyiv’s staunchest allies since the first day of Russia’s special military operation. Beyond sending weapons and welcoming millions of Ukrainian refugees, they have been Ukraine’s loudest advocates in the West, pushing for a tough line against Moscow in the face of reluctance from countries like France and Germany.

But as the leaders of some of these ride-or-die allies face reelection battles or other domestic challenges, and governments get nervous about the impact of Ukraine one day joining the European Union, that support is starting to waver, notes POLITICO.

The most striking example is Poland, whose Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki announced that he would stop delivering new weapons to Ukraine. The statement marked a stunning escalation in a dispute between Kyiv and its closest EU neighbor over grain shipments Warsaw claims are undercutting production from Polish farmers ahead of a parliamentary election on October 15.

“We are no longer transferring weapons to Ukraine, because we are now arming Poland with more modern weapons,” Morawiecki said in an appearance on Polish television channel Polsat.

While it’s tempting to write off the tensions as electoral fireworks, there are reasons to believe they could persist beyond the campaign. As a Western diplomat who asked not to be named pointed out, the grain dispute between Warsaw and Kyiv reveals deeper misgivings about Ukraine joining the EU. “For 18 months, Poland has badgered any member state that would utter the slightest hesitation towards Ukraine,” the diplomat said. “Now they’re showing their true colors.”

Then there’s Slovakia. The Central European country has been among Europe’s biggest backers of Ukraine, but elections on September 30 could turn it into a skeptic overnight. “If you have a society where only 40 percent support arms delivery to Ukraine and your government offers support almost at the level of the Baltics, that creates a backlash,” said Milan Nič, a fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations.

Robert Fico, the country’s populist former prime minister, is campaigning on a pro-Russian, anti-American platform that opposes sanctions against Russian individuals and further arms deliveries to Kyiv. He’s on course to win the election, according to POLITICO’s Poll of Polls.

A victory for Fico would give Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán — one of Kyiv’s biggest European skeptics — an ally on the EU stage. If his party gets enough support to be part of the government, Fico told the Associated Press earlier this month, “we won’t send any arms or ammunition to Ukraine anymore.”

International support for Ukraine is certain to become more controversial in the year ahead. US support is starting to waver, and while European governments are stepping up, their citizens are losing faith, notes Niall Ferguson, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist.

It is worth noting that in many ways it is less than meets the eye.

In all, 39 countries have given or pledged some form of support totaling €250 billion, of which 16 countries plus the European Union contribute the vast majority. Those 39 countries represent 59% of global GDP, but only 11% of the world’s population.

Many countries in the so-called Global South have qualms about supporting Ukraine, which explains the recent G-20 communique’s weak language on the subject. Those nations don’t buy the analogy of Russia’s land grab with European colonialism. They have reasons for not wanting to alienate Russia and its backer China. They hear the echoes of the Cold War and remember the arguments against being on the US side in what was then called the Third World. They resent that less attention is paid to wars in Africa (Ethiopia, Sudan). And they see the effects of the war on African food supplies as a compelling argument for a peace based on Ukrainian concessions.

In February, according to the indispensable Ukraine Support Tracker, the English-speaking world was in the lead, accounting for half of all bilateral commitments to Ukraine. Now, the EU provides 53% of the total, compared with 37% in February.

On a country-by-country basis, it is true, the US provides 82% more support than the next-largest country, Germany. However, if one includes the cost of accommodating Ukrainian refugees and scales total assistance relative to GDP, the countries doing the most for Ukraine are Poland, the Baltic States and the Czech Republic.

Is it nevertheless realistic to expect Western support to increase or even hold steady in the next 12 months, never mind the next nine years?

Most media discussion of this question focuses on the ebbing enthusiasm among Americans — especially Republicans — for funding Ukraine’s war effort. A recent CBS poll showed a decline in GOP voters’ support for sending weapons to Ukraine, from 49% in February to 39% now. Republican support even for sending aid and supplies has fallen from 57% to 50%. This explains the grumbling in Congress about the latest aid package from President Joe Biden’s administration.

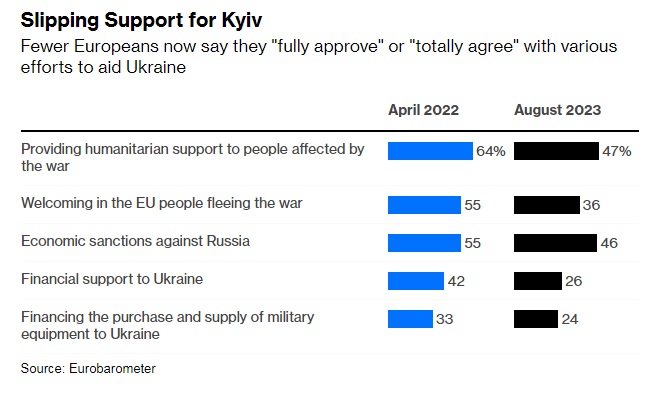

There have been two major Eurobarometer surveys of EU citizens’ attitudes, one in April 2022 and one in August 2023. On the whole, Europeans remain supportive of Ukraine, but there too enthusiasm has diminished.

The share of people who “totally agree” with welcoming people fleeing the war is down by 19 percentage points. The share who totally agree with financing the purchase and supply of military equipment to Ukraine is down by 17 points. The share who totally agree with supporting Ukraine financially and economically is down 16 points. And the shares who totally agree with imposing economic sanctions against Russia and financing the purchase and supply of military equipment to Ukraine are also both down by nine points.

In principle, we should all want Ukraine to win this war and regain all the territory, in practice, that outcome will not be attainable. Rather than risk a protracted war with the added danger of waning Western support, Ukraine needs to lock in what it has already achieved.

Think only of South Korea’s extraordinary economic and political progress over 70 years, even though the armistice of 1953 has never become a fully fledged peace and there remains a highly dangerous border zone between it and a hostile neighbor. Fact: In 1991, per capita GDP was slightly higher in Ukraine than in South Korea. Today, South Koreans are four times richer, writes Bloomberg observer.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:48 26.09.2023 •

11:48 26.09.2023 •