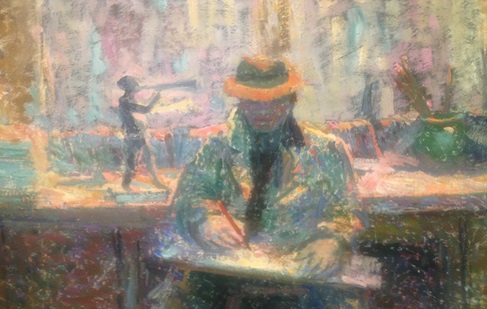

Rein Tammik. Boy with a Camera. 1981. State Tretyakov Gallery

Rein Tammik. Boy with a Camera. 1981. State Tretyakov Gallery Nikolai Kormashov. Near Chudov Lake. 1965. State Tretyakov Gallery

Nikolai Kormashov. Near Chudov Lake. 1965. State Tretyakov Gallery

How has the collaboration between Russian and Estonian museums developed in the post-Soviet period? Professional relationships are often mediated by the politics of the day, but as far as I know, the Tretyakov Gallery staff and their colleagues from Estonian museums have always kept in close contact, haven’t they?

E.K.: That’s true indeed. Our connections with Russian museums have always been very close, and not just with the Tretyakov Gallery. During perestroika and in the 90s our connections were also very tight, especially with artists and curators, who were very open-minded. Art was beyond politics then. In the field of classical art, museum collaborations have also been strong and prolific. In the Soviet time and after independence, the Kadriorg Art Museum known for its rich collection of Russian art of the 18th-19th centuries, has had quite intensive connections with the Russian Museum and as a result, last year we had a very successful Aivazovsky exhibition. Also, in the Soviet time, the Estonian Art Museum often used Hermitage specialists for their expertise and restoration skills – they were considered the best in their field. The Dance of Death by Bernt Notke, the most famous and valuable artwork in Estonia and the only surviving medieval danse macabre painting in the world, was in very poor condition. It was successfully restored at the Hermitage.

T.Z.: I would like to add that the current show is also remarkable because it allowed us after so many years to work as a team – productively and efficiently. Any decision-making process was a joint effort. At the end of last year, we visited KUMU to study the collection and in February 2018 our Estonian colleagues came to Moscow to select the exhibits. I backed the idea of including more works from the 1920s–1930s, which are less familiar to the Russian audience, but because the Estonian side does a lot of exhibitions abroad, we were able to fulfil it only on a limited scale. When I showed the material from Estonia to my colleagues here, they found it truly amazing – even specialists have never seen art of that time from Estonia, which is hardly surprising, it was seen as a bourgeois tendency and banned here. Professionals are taking the show with much enthusiasm; hopefully the general public will like it too.

Malle Leis. Woman Leaving. 1970. Art Museum of Estonia

Malle Leis. Woman Leaving. 1970. Art Museum of EstoniaE.K.: I think the Tretyakov Gallery collection is the biggest, luckily in the Soviet time it was the duty of the museum to collect art from the republics. We have some Estonian art in Finnish museums, but it’s mainly old and pre-war art. Estonian art is scattered in various collections across Europe; a very interesting and diverse art collection is in Toronto, where many Estonians moved in 1944: all of them left Estonia with the art dear to them, though the condition of these works often left much to be desired. Later in the 1960s, they set up the Centre of Estonian Art in Canada. But none of those collections are as solid and well-researched as that of the Tretyakov Gallery. What also makes it truly unique is the quality of art – the standards for museum works were very high.How did it come about that the Tretyakov Gallery boasts such a rich collection of Estonian art of the 20th century? When was the collection established and what were the main stages of building it?

T.Z.: It was established shortly after the war – the first acquisitions dating to 1946, when the very first art exhibition of the Soviet republics took place at the Tretyakov Gallery. Building the collection spanned almost 40 years; it was a gradual process – from the mid 1940s to 1990s. In the 80s I was a member of the Acquisition Committee (Department) to the Ministry of Culture and regularly participated in buying art from all the republics, including Estonia. However, the most valuable contribution to the collection came in 1986, when the funds of the Union of Artists were united with the Tretyakov Gallery collection. Artworks amassed by the Union of Artists were less ideologically charged – they enjoyed more freedom in selecting what to buy and who to buy from. Due to this fact our museum collection had the best works possible and today we even have some works of that period that Estonian museums lack.

Aili Vint. Waiting for the Wind. 1979. State Tretyakov Gallery

Aili Vint. Waiting for the Wind. 1979. State Tretyakov GalleryT.Z.: The collection incorporates hundreds of paintings, approximately 53 sculptures and a vast collection of graphic art, including bookplates that were hugely popular in Estonia from the 1920s onwards. The tradition carried on and culminated in the 1970s–1980s, when graphic techniques, especially the woodcut, were raised to an exceptional level. Over these years some artworks from our collection participated in various exhibitions in Russian museums, but there has been nothing of the scale of the current show since 1997.

Krista Mölder. Photo from the series Not Leaving a Room. 2016. Art Museum of Estonia

Krista Mölder. Photo from the series Not Leaving a Room. 2016. Art Museum of EstoniaThe exhibition concept is not chronological, but structured around key themes and ideas. Why have you selected these particular five topics?

E.K.: The exhibition is divided into five sections: “The Classics”, “Teacher and Student”, “Seascape”, “Here and Elsewhere”, and “Female Artists”. We decided to get away from the chronological approach and represent almost 100 years of Estonian art through a dialogue of masters, themes and genres. The themes that run through the exhibition explore the concepts of border and place, and how their meanings have changed over time. Deciding on the exhibition sections, we also looked at statistics and overarching themes in the collection. Thus, landscape painting belonged predominantly to the “seascape” category. Not only because it is a representative image of Estonia, a symbol of the region, but also a colonial way of looking at the Baltics. The section focusing on female art was built around works by Malle Leis, whose legacy is well represented in the Tretyakov Gallery collection. I decided to make her a pivotal figure and group other female artists around her. Feminist tradition has been quite strong in Estonian art.

Where does the exhibition title come from? Was it conceived with the concept of the show?

E.K.:In Estonian, the word “border” has many meanings, and is not limited to an association with state borders. The phrase “border poetics” is broadly used in postcolonial studies related to social and cultural experiences, which, among other things, deal with how borders are depicted. Border experiences have enriched Estonians in their search for their roots and their foundations, as well as in their art practices. Speaking about borders we mean not only a physical barrier, but also inner, mental boundaries that are never solid – there are always gaps and holes. It has been proved by the Soviet system and is equally relevant in our time of the Internet.

Why did you devote the special section “Teacher and Student” to Elmar Kits and Ülo Sooster?

E.K.: It was not a matter of comparing or drawing parallels between their lives, though the title of the section does suggest so – Elmar Kits was ÜloSooster’s teacher at Tartu Art School. But by focusing on these two artists we mainly wanted to emphasize the exceptional influence they both had on Estonian art and the Russian non-conformist art scene of the time as well as their pioneering role in the art of 20th century Estonia and Russia. In some way Elmar Kits had a deep impact on all Estonian artists of his generation. His own path in art was exceptionally broad and prolific – he started as a representative of the French school, then switched to socialist realism, but completely reworked it, and in the 1960s, at the first opportunity, proceeded with abstract art.

Elmar Kits. Artist. 1945. Tartu Art Museum

Initially Ülo Sooster became well-known as a member of the Moscow underground art scene, together with his friends and colleagues creating a cultural connection between Moscow and Tallinn in the 1960s, which proved to be crucially important for visual culture in the Soviet Union and for Moscow conceptualism that was yet to come. When Ülo Sooster died in 1970 his friends and colleagues – Ilya Kabakov and Yury Sobolev decided to pass on his collection – a huge legacy of over 3000 works – to Estonia. Only one small part of those works was connected with Estonia, everything else was related to Russia and his experiments of the 1950–60s. He equally belongs to both cultures.

Images: by Elena Rubinova and courtesy of KUMU Press Department

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

13:02 26.11.2018 •

13:02 26.11.2018 •