The Department of History and Records expresses its gratitude to Ambassador Anatoly Adamishin for the letters of Clementine Churchill that were sent to the Foreign Policy Archives of the Russian Federation.

Photos - Archive of the foreign policy of the Russian Federation. F. 06. Op. 1. P. 3. D. 13. "The Molotov Album."

The public, humanitarian and, to a large extent, diplomatic activity of Winston Churchill's wife, Clementine, is inextricably linked with the Soviet Union and its struggle against German Nazism. Clementine Churchill’s active and selfless wartime effort in support of our country revealed to the whole world not only the business acumen, outstanding organizational and leadership skills, but also the impressive personal qualities of this wonderful woman.

It would be safe to assume that in her position as the head of the Red Cross Aid to Russia Fund, Clementine Churchill became (emerging from the shadow of her husband) an independent historical figure, who won well-deserved international acclaim and recognition.

The British Red Cross had been helping the Soviet Union since the very start of the Nazi German aggression against the Soviet Union, even before the Fund actually came about. However, just as the Soviet Ambassador to Britain, Ivan Maisky wrote in his diaries [1], the nature of that initial approach was rather “formal” and “bureaucratic.” Shortly after June 22, the embassy received £75,000 from the Red Cross, but during the flowing three month no more funds were forthcoming.

Meanwhile, the degree of the British people’s empathy with and support for the Soviet Union was rising fast. In the absence of "centralized" financial assistance coming in the course of several months, the embassy was getting numerous donations from individual British citizens. Small as these donations usually were, their number and the desire of Britons from all walks of life to contribute to the Soviet people’s struggle against Nazism was absolutely amazing. [2]

The embassy was doing its best to express its gratitude, with each donor receiving, in addition to a receipt, also a special “thank you” note.

“Those messages of gratitude could have been either formal and stereotype, saying only that the donation had reached its intended purpose, or carry a more serious content that could strengthen the giver's faith in our country’s ultimate victory. We chose the second option.” [3]

Pro-Soviet sentiments also dominated the British establishment, whose desire to provide maximum support for the USSR was largely fueled by the feeling of awkwardness and guilt for their foot-dragging on opening the Second Front. Strange as it may seem today, back in those days, British politicians were fully aware of and guided by a moral duty to the Soviet Union, which was actually left alone to fight the military machine of the German Reich.

It was then that they decided to establish a dedicated Aid to Russia fund as part of the British Red Cross for systematic and orderly collection of funds, the organization of purchases and supplies to the USSR of items of primarily medical nature.

As Clementine Churchill wrote: “I was terribly worried by the great drama that broke out in your country immediately after Hitler’s attack. I kept thinking how we could help you. At that time, the question of a second front was widely discussed in England. I once received a letter from a group of women whose husbands and sons served in the English army. They insisted on opening the second front. I then thought: ‘If these women demand a second front, that is, they are ready to risk the lives of their loved ones; it means that we must immediately help Russia.’

I showed the received letter to my husband. He replied that the second front is still very far away. This alarmed me greatly, and I began to think about what could be done now, immediately, to help your country. Then the thought of the Red Cross Foundation came to me.”4

Winston Churchill enthusiastically embraced his wife's initiative and contributed in every possible way to its rapid implementation by allocating significant administrative and information resources of the government for that purpose. Important as such high-level support was, however, it still was not a key factor in the effective and large-scale work being done by the Fund. Ivan Maisky repeatedly praised Clementine's constant care and sincere enthusiasm for the activities of the new organization, and her invariably active personal participation in resolving complex issues.

In a conversation with Maisky, Winston Churchill joked about his wife’s activities: “My own wife was completely Sovietized! She only talks about the Soviet Red Cross, about the Red Army, about the wife of the Soviet ambassador she writes to, telephones to and speaks with during rallies.” Then, with a sly sparkle in his eyes, he added: “Can't you elect her to any of your councils? She really deserves it." 6

The Aid to Russia Fund began its activities on October 7, 1941. The campaign enjoyed the undivided support of people from across the British society. Clementine Churchill later wrote that the Fund was seen by the British as an opportunity to express in practice their admiration and sympathy for the Russian people in their heroic struggle. During the first 12 days of its activity alone, the Fund managed to raise 370,000 pounds, with the first 1,000 pounds donated by the King and the Queen. Within a few weeks, by December 1941, the initial goal of raising one million pounds had been achieved.

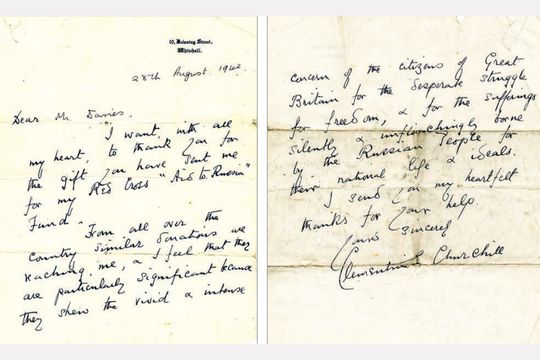

“28 August, 1942

Dear Mr. Davis,

I send you my warmest thanks for your generous contribution to my 'Aid to Russia' fund. I have been receiving similar donations, from all across the country. I believe they are extremely important as they reflect the sincere and profound empathy our British citizens feel for the Soviet people’s desperate struggle for freedom, and the suffering they endure with tacit fortitude in the fight for a normal life and their ideals.

I am sending you my heartfelt thanks for your help.

Sincerely yours,

Clementine Churchill."

The documents of the Soviet People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs [9] reflect Clementine's informal approach to her noble humanitarian mission and sincere concern for her new brainchild. So great was her fundraising activity that the Aid to Russia Fund became inseparably associated with her, and everyone began to informally refer to it as "Mrs. Churchill's Fund."

Her organizational and media activities deserved special praise for being "of great political importance, because her words are listened to and trusted by business circles, the right-wing circles within the Conservative Party and other elements, who usually perceive positive accounts about the Soviet Union with distrust." So were the diplomatically and undeservedly mild - but not for those who can read between the lines – descriptions of her success in winning over to the bright side those members of Britain’s upper classes who had previously openly sympathized with Germany and Hitler’s regime.

“December 1942

You were one of the sympathetic friends who responded to the call I made a year earlier to donate to the Red Cross Aid to Russia Fund, and turned it into a monument to the Russian people. We have raised nearly two and a quarter million pounds. All this - and even more - has already been spent and Russian citizens still need and more than ever deserve all the medical and surgical supplies and all the comfort and support we can give them.

On New Year's Eve, I will make another appeal. I look forward to the support and cooperation of the whole country in the coming months.

Could you please help me again as you did before?

Sincerely yours,

Clementine Churchill."

Notably, it was ordinary Britons, not representatives of the country’s elite, who were largely and willingly donating to the Fund, even though they themselves were suffering the hardships brought by the war. The money that was being sent to the Fund contained neither any requests, nor conditions, for that matter. [11]

In her September 29, 1943 interview with The Times, Clementine described the money raised by the Fund as a “sincere tribute” to Britons across the globe. She added, however, that although wealthy people were donating generously, most of the money was still coming from ordinary workers, hundreds of thousands of whom were contributing week in and week out. She wrote that it was truly a people's fund though which the British expressed their respect, surprise and admiration for the Soviet people’s unrivalled bravery, patriotism and military successes. [12]

By January 1945, the Fund had already sent four million pounds’ worth of goods to the Soviet Union, including 11,600 tons of medical items and clothing, 2,000 tons of medicines, 22,000 units of medical equipment, including 600 autoclaves for sterilization, 600 X-ray units, surgical instruments, many of which made to conform with Soviet standards, as well as equipment for two prosthesis-making factories.

The Fund took special pride in helping rebuild and re-equip the Clinical and Central City hospitals in Rostov-on-Don, at the cost of 400,000 pounds.

By the end of the war, total donations had exceeded £7 million.

Shortly before the end of the war, the Soviet government, in a sign of appreciation for Clementine Churchill’s humanitarian effort, invited her to pay an official visit to the USSR.

Apart from Moscow, the program of her visit included trips to cities, which had benefited the most from the Fund’s activities: Leningrad, Peterhof, Stalingrad, Kislovodsk, Essentuki, Pyatigorsk, Rostov-on-Don, Sevastopol, Yalta, Odessa and Kursk. The latter was originally absent from the list and was added at the very last moment at the request of the city's residents.

Clementine Churchill was to meet with local officials and representatives of the public at hospitals and social infrastructure facilities.

She was received with all due pomp and circumstance, which, while reflecting the feelings of gratitude by the country’s leadership and the entire Soviet people to her, and in her person, to the people of Great Britain, was also meant to demonstrate the country’s economic strength and the creative potential of its people, despite all the devastation caused by the war. [13]

The meeting that Clementine Churchill had at the start of her visit with Josef Stalin was of a strictly protocol nature, meant to underscore her high status. As can be seen from the recording of that conversation [14], being people of high diplomatic culture and tact, Clementine and Stalin perfectly played the roles assigned to them by the occasion. They avoided acute political issues and refrained from making any requests, sticking to expressions of gratitude, questions about the family and the upcoming journey, despite the fact that Stalin was well aware of the influence that Clementine had on her husband. And Clementine, knowing full well that the Soviet leader was perfectly aware of this, as well as of her personal contribution to the Soviet victory in the war, had every moral right to bring up certain aspects beneficial to Great Britain. By the way, Winston Churchill himself never used his wife’s Fund as a bargaining chip when dealing with Stalin. [15]

During the trip, Clementine had a chance to see with her own eyes the level of destruction and the depth of grief that the war had brought to this country. And yet, she was profoundly impressed by the resilience of the Soviet people, their undying optimism and desire to return to normal life as soon as possible. She later wrote that what had struck her the most during that trip was the fact that wherever she went she saw the Soviet people’s uniquely courageous attitude towards disasters. [16]

Despite the difficult economic situation in the country, people tried to make Clementine feel as comfortable as possible and literally showered her with gifts. This attitude was certainly not lost on their guest, who described the Russian hospitality as unusually wide, but, at the same time, more cordial and attentive than ostentatious. “Russians like making presents much more than to accept them,” she wrote. [17]

The most expensive present that she received here was a 5.58-carat diamond ring given her upon her return to Moscow by Vyacheslav Molotov’s wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina. Clementine Churchill later recalled how, during a breakfast given in her honor by the Soviet government two days before her departure, Mrs. Molotova presented her with a diamond ring of the purest water, mined in the Urals.

“We ask you to accept this ring as a token of our eternal friendship. May the relations between our two countries be as clear, pure and eternal as this stone,” Molotova said. Clementine responded by saying that she would always regard that ring as a symbol of the valor of Soviet women, whose heroism, displayed during the war and in post-war restoration of their country, was widely admired everywhere. She also admitted that the beauty of that stone made her feel genuinely pleased as a woman. [18]

The visit culminated in Clementine Churchill being awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor and the honorary badge of the Russian Red Cross. This was the final formal act of mainly political recognition of her wartime assistance to the Soviet Union. She still tried to avoid any politicization of that event, considering it exclusively as her humanitarian and public mission.

“I will always cherish the orders I received in Moscow, as a token of friendship created by our foundation ... in addition to easing the people’s suffering though the supply of funds and supplies, interaction between the Russian Red Cross and our Fund is extremely valuable in cementing the friendly relations between Russia and Great Britain. I felt that the Fund made a valuable and lasting contribution to this great cause.” [19]

“My dear Mr. Molotov,

I am writing to you to say that I will never forget the wonderful time I have had in your country.

I want you to know how kind and attentive Mrs. Molotova was to me and how much she did to ensure my pleasant stay here.

I wish I could have been able to tell you this in person.

I am sure you would very much like to be here and see the sunrise of victory and peace over Moscow.

May it shine as long as possible over our beloved countries and over the whole world.

Sincerely yours,

Clementine Churchill. "

Upon her return to Britain, Clementine Churchill wrote a short essay “My Visit to Russia,” published a month later by the London publishers Hutchinson & Co. Ltd. I immediately ordered its translation into Russian. The English version, printed in the harsh post-war conditions on rough, low-quality newsprint with a primitive glued cover, was selling in Britain, North America and Australia for one shilling apiece. Out of respect and gratitude for the warm welcome accorded Clementine Churchill in the USSR, the Russian-language version was printed on expensive, top-quality paper in a leather cover, embossed in gold. [20]

A number of books with a handwritten dedication were donated to Clementine's acquaintances in the Soviet Union.

Although her reception in the Soviet Union was conceived as a political act of gratitude for her contribution, as a formal episode of her work, it proved to be more than just a formality. The Aid to Russia Fund continued its work after the defeat of Nazi Germany and even after Winston Churchill delivered his famous Fulton speech. Donations stopped being accepted only in January 1948, with the total sum exceeding 7.5 million pounds. Supplies of humanitarian aid purchased with those funds to the Soviet Union continued until the end of the 1950s. [21]

In hindsight, Clementine Churchill's wartime work as the head of the Aid to Russia Fund can be viewed as a graphic example of people’s diplomacy, which was far ahead of its time. Noble goals, specific tasks, real deeds, and a minimum of politics… “We saw all the obstacles created by the difference in our languages, customs and geography disappear when Russian and British cities were welded together by a common struggle against the merciless enemy. I would hate to see this sense of community fade in the future,” she wrote.” [22]

Unfortunately, this is exactly what happened. The groundwork prepared by Clementine Churchill remained unclaimed, abandoned and, as a result, completely and undeservedly forgotten. The archaic nature of the 1940-1950s politics and the outbreak of the Cold War prevented this process from coming to fruition, leaving the bridges of friendship and mutual understanding unfinished.

Still, these were outstanding achievements of a woman leader. Although in such cases one’s social standing does matter, of course, the role of personality is always a decisive factor of mutual attraction, trust and leadership.

What makes the phenomenon of Clementine Churchill's diplomatic success so unique is that she achieved major results without playing any particular social or political roles, and always remained just a woman, sensitive, responsive and empathic. Perhaps, it was her feminine warmth, care and compassion that allowed this woman to achieve so much more than just cold calculus and soulless rationality, which, sooner or later, lose in the fight for the hearts and minds of people, who eventually get sick and tired of them. Clementine, with her sincerity and openness, lit up the gloomy and soulless picture of political expediency, bringing into politics a sense of mercy, which is the best human quality a person is endowed with.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 I.M. Maisky. Memoires of a Soviet Diplomat, 1925-1945 2nd edition, Moscow, Mezhdunarodnye Otnosheniya Publishers 1987. pp. 711-712.

2 Knight Claire. Mrs. Churchill Goes to Russia: The Wartime Gift-Exchange between Britain and the Soviet Union // A People Passing Rude: British Responses to Russian Culture / Edited by Anthony Cross. Open Book Publishers, 2012. Р. 254.

3 I.M. Maisky. Ibid. p. 705.

4 Ibid. pp. 711-712.

5 Ibid. pp.708, 709, 711-712.

6 Ibid p. 711-712.

7 Clementine Churchill “My visit to Russia” London, 1945. p. 5.

8 Knight Claire. Op. cit. P. 254-255.

9 Foreign Policy Archives of the Russian Federation. “C. Churchill’s stay in the USSR.”

10 Ibid.

11 Knight Claire. Op. cit. pp. 255-256.

12 See Foreign Policy Archives of the Russian Federation. “C. Churchill’s stay in the USSR.”

13 Knight Claire. Op. cit. Р. 259-260.

14 See Foreign Policy Archives of the Russian Federation. “C. Churchill’s stay in the USSR.”

15 Knight Claire. Op. cit. p. 257.

16 Churchill Clementine, Op. cit. p. 13.

17 Ibid. P.10.

18 Ibid. p.18.

19 Ibid. p. 17.

20 Knight Claire. Op. cit. pp. 261-262.

21 Ibid. pp. 255-256.

22 Churchill Clementine. Op. cit. p. 6.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

16:16 29.12.2020 •

16:16 29.12.2020 •