In March 1939, weeks before the notorious White Paper, Polish Jewry sent London a desperate telegram, published here apparently for the first time. At terrible cost, it was ignored.

The sordid history of the May 1939 British White Paper, the notorious document with which the British all but slammed shut the doors of Palestine to European Jewry, has been documented many times. Less-remembered is how the (Jewish-owned) New York Times took British prime minister Neville Chamberlain’s side the day after the White Paper was issued, incurring the wrath of Chaim Weizmann and the Zionist leadership. Virtually unknown, however, is that the Polish Jewish community had sent a desperate plea two months earlier to Chamberlain — a telegram begging him to keep the gates of Palestine open.

This is the story of that plea.

Although the dispatch of the telegram was reported at the time, this article apparently marks the first time the document itself is being published.

The missive was discovered after 82 years in a British Colonial Office file; there is no evidence that Chamberlain or anyone in his office discussed it or, indeed, ever even saw it.

***

By late 1938, the Jewish position in Europe, already precarious in Germany and countries under the threat of German invasion, had worsened dramatically. On September 30 of that year Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement, allowing Hitler to annex the Sudeten areas of Czechoslovakia.

Chamberlain naively believed appeasement would bring “peace in our time,” but in actuality, the opposite occurred — Chamberlain’s weakness emboldened Hitler to launch World War II just 11 months later. By June 1940, Hitler was bombing the civilian population of London.

The Munich Agreement also paved the way for the Holocaust, which began less than six weeks later with the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9, 1938. Thousands of Jewish businesses and synagogues were destroyed throughout Nazi Germany. Hundreds of German Jews lost their lives in the overnight orgy of violence, a precursor to the fate awaiting six million other Jews throughout Europe. After Kristallnacht, no one could claim ignorance of Hitler’s intentions toward the Jews.

As 1939 dawned, the outlook for European Jews had never been worse. The Jewish Agency desperately urged the British government to allow more European Jews to immigrate to Palestine. The Arab Higher Committee, representing the Palestinian Arabs, adamantly opposed any further Jewish immigration.

In Palestine, the Arab Revolt inspired by Haj Amin Al-Husseini, the grand mufti of Jerusalem and acolyte of Hitler, had been raging for nearly three years, costing hundreds of lives. The British government abandoned the Palestine partition scheme its own Peel Commission had urged in a comprehensive 1937 report.

The Woodhead Commission, appointed to conduct a follow-up technical analysis of the Peel Commission’s partition proposal, declared the plan unworkable. In a cruel twist of irony, the Woodhead Commission published its report on November 9, 1938, only a few hours before the onset of the Kristallnacht pogrom.

In the wake of the commission’s findings, the British government announced it would invite representatives of the Palestinian Arabs and the neighboring Arab states, as well as representatives of the Jewish side, to a conference in London in early 1939 to discuss the future of Palestine.

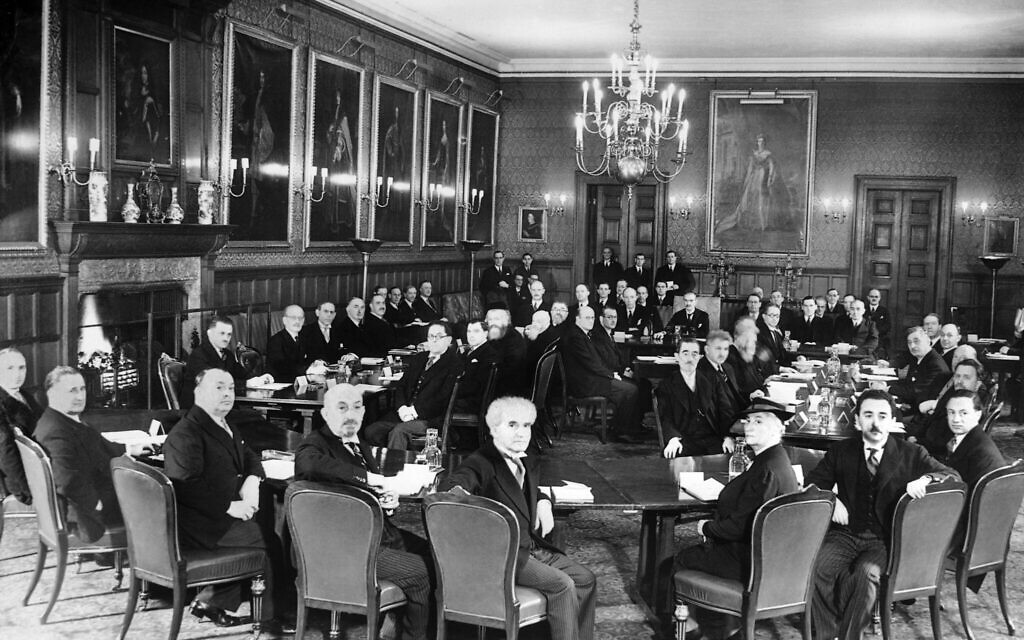

The London Conference opened on February 7, 1939, at St. James’s Palace. Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, later the first president and first prime minister of the future State of Israel, respectively, led the Jewish delegation.

In his opening statement — made to the British Government and Jewish delegates only, as the Arab delegates refused to sit in the same room with the Jews — Weizmann stressed the extreme danger Hitler posed to European Jewry, prophetically noting “the fate of six million people was in the balance.”

But Weizmann’s warnings fell on deaf ears. By late February 1939, less than three weeks after the London Conference began, British officials began leaking to the press their intention to propose independence for Palestine in 10 years under majority Arab rule, along with immediate and severe limitations on Jewish immigration to Palestine.

As the Times of London reported on February 28, 1939, “[t]he Arabs were jubilant about the proposals, the Jews cast down and bitter.” The same Chamberlain who foolishly believed appeasing Hitler represented the best way to keep the peace in Europe not surprisingly decided that appeasing the mufti was the best way to restore peace to Palestine.

By mid-March everyone realized Britain planned to close the doors of Palestine to all but a small trickle of Jewish immigrants. On March 15, 1939, the Times of London published additional leaked details of the British proposals for Palestine, including capping Jewish immigration at 15,000 per year for the next five years.

That same day, March 15, 1939, Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, and German forces triumphantly marched into Prague.

The Jewish community in Poland followed the ominous developments at the London Conference and in Czechoslovakia with increasing alarm and worry. The German military action against neighboring Czechoslovakia raised the unmistakable and terrifying specter of a potential German invasion of its other eastern neighbor, Poland. That prospect, combined with the news leaks from London indicating Britain planned to virtually close Palestine to further Jewish immigration, plunged Polish Jewry into crisis.

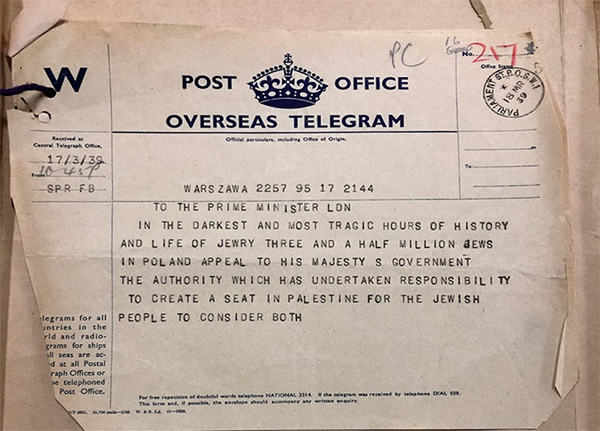

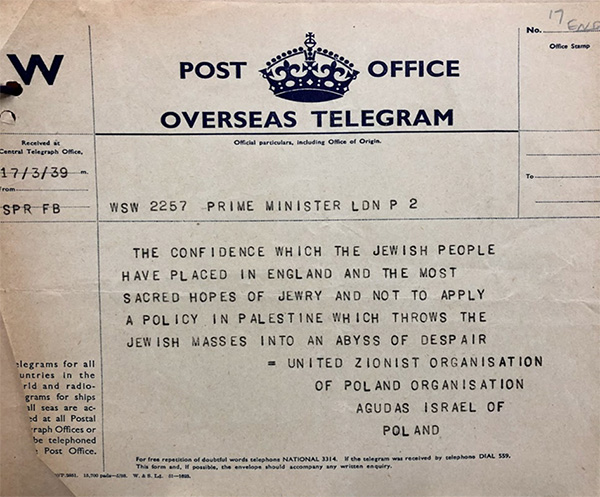

Against this backdrop, two days later, on March 17, 1939, the United Zionist Organization of Poland and Agudas Israel of Poland sent a desperate, two-page telegram to Chamberlain. The telegram begged the prime minister of the United Kingdom to keep the doors of Palestine open to Polish Jewry, to allow them at least a chance of escape from the imminent Nazi threat.

This is the text of the original telegram:

In the darkest and most tragic hours of history and life of Jewry three and a half million Jews in Poland appeal to His Majesty’s Government the authority which has undertaken responsibility to create a seat in Palestine for the Jewish people to consider both the confidence which the Jewish people have placed in England and the most sacred hopes of Jewry and not to apply a policy in Palestine which throws the Jewish masses into an abyss of despair.

The Jewish Telegraphic Agency’s Warsaw office published a brief dispatch two days later, March 19, 1939, headlined “Polish Jews Ask Britain to Keep Faith.” The dispatch purported to quote from a telegram from Polish Jewry to the British Government, but the language was different from the original telegram shown above:

In the darkest and most tragic hour of Jewish history, three and a half million Polish Jews appeal to the British Government not to betray the confidence of the Jewish people in Great Britain and not to destroy the sacred hopes of the Jewish people by adoption of a policy bound to drive them to despair.

Perhaps the language quoted in the JTA dispatch was from an earlier draft of the telegram, or perhaps the author of the dispatch failed to record the exact language of the original telegram. In any event, it appears the original telegram has never previously been made public, until now. That is not surprising, given the telegram has sat unnoticed for the past 82 years in a British Colonial Office file marked “Palestine: Original Correspondence.”

A variety of experts have been consulted, all of whom reported they had not heard of the telegram or seen it published anywhere.

Prof. Dan Michman, head of the International Institute for Holocaust Research and incumbent of the John Najmann Chair of Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, said he had not previously seen it, but cautioned against “overstating the importance and impact of one telegram.”

Prof. David Engel of New York University, a leading expert on the history of Polish Jewry and the Holocaust, said he did not recall any discussion of the telegram in the relevant literature.

The research staff at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, indicated they had not previously seen the telegram either, but brought the above-referenced JTA dispatch to this reporter’s attention.

Tragically, the original telegram failed to move the British government. Indeed, none of the relevant British government files reflect any internal discussion of the message, including whether the prime minister or anyone in his office ever saw it. Nor did the British Government offer any response to the Jews of Poland, until it released the White Paper announcing the government’s new Palestine policy exactly two months later, on May 17, 1939.

The White Paper imposed extreme limits on Jewish immigration to Palestine, capping the influx at a maximum of 75,000 total Jewish immigrants for the entire five-year period between 1939-1944.

By the time of the White Paper’s publication, the telegram from Polish Jewry had been buried in the files of the Colonial Office, where it remained concealed from public view for the next 80 years, until now.

The result of the White Paper’s immigration policy was catastrophic: of the six million Jews on whose behalf Weizmann had appealed in his opening statement at the London Conference, 5,925,000 were condemned to remain in Europe. Of the 3.5 million Polish Jews who had begged Chamberlain for help in March 1939, only 75,000 were still alive by early 1945. Regardless of motive or intention, Hitler and Chamberlain seemed to be operating in a tacit alliance to condemn Europe’s six million Jews to death.

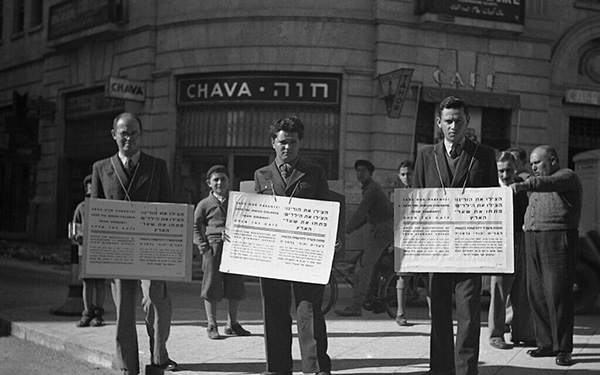

The Zionist leadership reacted to the White Paper with fury, sending letters of protest and a comprehensive legal memorandum to the British government and the Council of the League of Nations.

Weizmann succeeded in obtaining a symbolic vote of disapproval from the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations, but it meant nothing to the doomed Jews of Poland and elsewhere in Europe.

One would have thought the White Paper and the plight of Polish and European Jewry must have provoked an outcry from other influential Jewish voices around the world. But one of the most important channels, the Jewish-owned New York Times, shockingly defended the White Paper in an editorial published May 18, 1939, the day after it was released.

The editorial, written only six months after Kristallnacht; two months after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Polish Jewish telegram; and less than four months before Germany’s invasion of Poland, callously proclaimed, “[t]he pressure on Palestine is now so great that immigration has to be strictly regulated to save the homeland itself from overpopulation . . .”

The editorial agreed with the British government that it was more important to avoid upsetting the Palestinian Arabs than to allow more than a tiny number of European Jews to immigrate to the country.

Weizmann was so furious with the Times that he refused to meet with the paper’s publisher, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, during Sulzberger’s visit to London a few days later. Weizmann vented his anger in a letter to Solomon Goldman on May 30, 1939, dismissing Sulzberger as a “cowardly Jew.” In the same letter, Weizmann asked Goldman, “what I would like to understand however is whether the general attitude and feeling of the [American] Jews is very different from Sulzberger’s and his paper.”

Even after WWII had ended and the Zionist leadership was begging the British government to allow 100,000 destitute and still endangered Holocaust survivors (“asylum seekers” in today’s parlance) to immigrate to Palestine, the New York Times continued urging appeasement of the Palestinian Arabs rather than allowing Europe’s surviving Jews to seek a new life in Palestine.

Commenting on the plight of European Jewry in a November 14, 1945, editorial, the Times coldly declared, “Certainly there is no indication that the solution will be found in mass emigration to Palestine.”

To his great credit, then-US president Harry Truman ignored the Times and publicly pressured prime minister Clement Attlee to set aside the White Paper’s restrictions and grant 100,000 immigration certificates to European Jewish asylum seekers.

Same threat, different day

Why should we care about any of this more than 80 years later?

Because history has a way of repeating itself. Anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment has swept across large swaths of Europe and the United States in recent years. More ominously for the Jewish people, anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism are converging and gaining increasing currency in Europe and the United States, on both the left and the right of the political spectrum.

The perfidy of Chamberlain’s Conservative government in issuing the White Paper and condemning millions of European Jews to the gas chambers must be remembered, lest history repeat itself.

For the sake of the nearly 3.5 million Polish Jews and the 2.5 million other Jews from the rest of Europe who perished so tragically and so needlessly, we must never forget what could have been done to save them.

***

Steven E. Zipperstein is the author of the forthcoming book, “Law and the Arab-Israeli Conflict: The Trials of Palestine.” Zipperstein is a former United States federal prosecutor, and now holds the position of senior fellow at the Center for Middle East Development at UCLA. He also teaches in UCLA’s Global Studies program and School of Public Affairs, and as a visiting professor at the Tel Aviv University Law Faculty. Copyright: Steven E. Zipperstein 2020.

timesofisrael.com

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

14:19 24.01.2020 •

14:19 24.01.2020 •