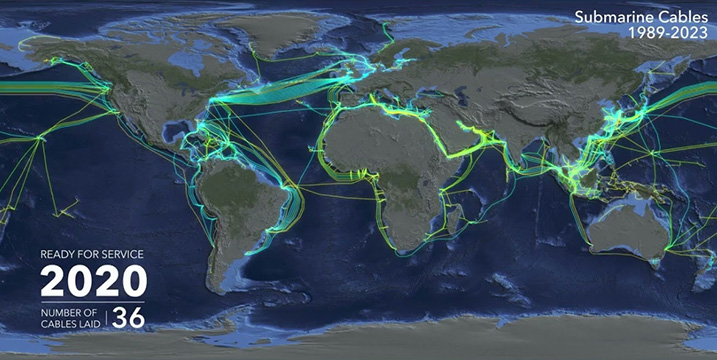

Beneath the ocean waves, over 700,000 nautical miles of undersea cables link the far reaches of the world. These cable networks transmit government and private messages between continents in seconds, thereby forming the information backbone of modern society, writes ‘The Engelsberg Ideas’. Undersea cables are the soft underbelly of American power. History demonstrates that protecting them is of critical importance.

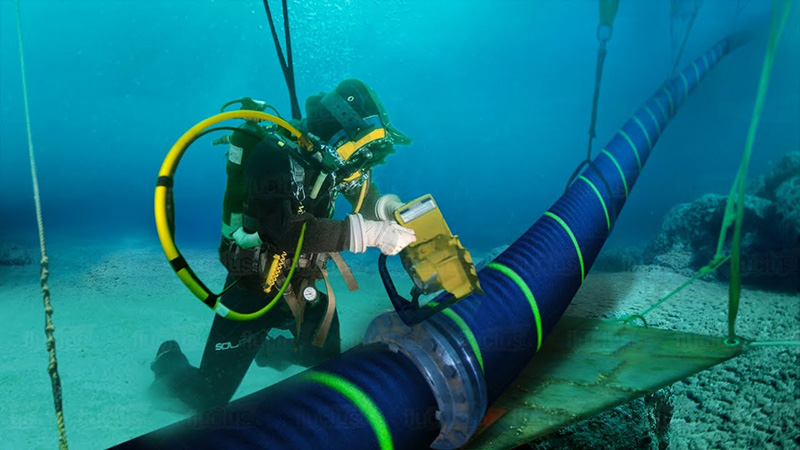

The ubiquity of connectivity has rendered this cable infrastructure a largely invisible part of daily life, but instances of natural and human interference with cables has underscored their fragility. Due to their singular importance, cables have become attractive military targets. In March 2024, Houthi rebels severed three undersea cables in the Red Sea, disrupting 25 per cent of Europe and South Asia’s internet traffic, and visibly demonstrating the far-reaching effects of even small-scale cable attacks.

There is nothing new about cable vulnerability. The United States cut undersea cables used by Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898, while the British cut German cables in the lead up to both the First and Second World Wars. Even with the advent of radio and satellite communications, cables have remained a core element of international telecommunications because of their high capacity.

A key lesson from telecommunications history is that being able to seamlessly move message traffic between different communications networks is vital for information security. The emergence of large-scale space-based internet services, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, provide an alternative pathway for routing data if cables have been cut. New space systems cannot, however, fully mitigate widespread cable losses.

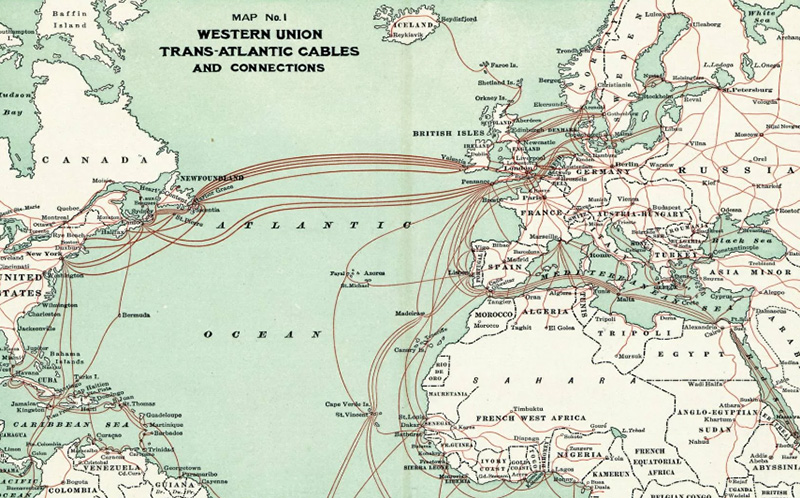

The 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed profound changes in communications technologies that shaped the global balance of power. In August 1858, Queen Victoria and President James Buchanan exchanged messages using the first undersea cable that connected Britain with North America. By the early 20th century, undersea cables served as the nerve system of the British Empire, linking London with its faraway colonies and dominions.

The dual use nature of undersea cables immediately raised questions about their security. In 1884, countries from around the world gathered in Paris at a meeting of the International Telegraph Union, the precursor to the current International Telecommunications Union, to develop specific protections for undersea cables. Those present ratified an agreement to protect undersea cables in times of peace and established specific liabilities for a party that cut a cable, whether intentionally or not. Government representatives recognised that cables would be valuable targets in wartime.

Western Union map showing routes of undersea telegraph cables in 1900.

Western Union map showing routes of undersea telegraph cables in 1900.

Pic.: Alamy Stock Photo

In the final decade of the 19th century, over 192,000 nautical miles of privately-owned cables and nearly 23,000 nautical miles of government-operated cables stretched under the ocean. At this point, two thirds of the world’s cables were British and one group, the Eastern and Associated Companies, owned approximately 45 per cent. Notably, the United States had not yet emerged as a global power and thus did not yet prioritise sovereign control over its strategic communications networks. Consequently, Britain was able to monopolise a significant portion of the global telecommunications network, ensuring the security of its information while being able to surveil messages transmitted by foreign powers.

In the 1920s a revolution in radio technology took place when shortwave radio hardware became widely available. This new technology bounced radio waves off the ionosphere, allowing messages to be sent over thousands of miles more inexpensively than cables. Quickly, businesses and individuals began sending more messages via radio than cable, threatening the viability of the global undersea information network.

The dangers of foreign dependence on telecommunications would become especially apparent during the First and Second World Wars. In each conflict, the British successfully cut German cables, forcing Berlin to rely on radio, which could be intercepted, or to send messages via British cables, which UK intelligence officers were monitoring.

By the end of the Second World War, the United States and Britain both possessed global telecommunications networks comprised of radio and undersea cables. The advent of the nuclear age made telecommunications security an even more urgent issue. Atomic weapons-testing demonstrated that a nuclear blast could render large portions of the ionosphere unusable for long periods of time, severely degrading radio communications.

In these circumstances, the United States increasingly looked to emerging satellite technologies to be able to communicate with conventional and nuclear units across the globe. In the mid-1960s the United States began launching the first wave of commercial and military communications satellites. Within a decade, communications satellites transmitted just over one third of all US military long-haul communications and provided connectivity for NATO allies as well. The United States still heavily depended on undersea cables and radio networks.

A little more than three decades after the Cold War ended, threats to global telecommunications networks have only multiplied.

Photo: mavink.com

Photo: mavink.com

At present, undersea cables, radio, and satellites are the three primary technologies that enable long-haul communications. Now, the global economy, and US national security organizations, are even more dependent on undersea cables for high-capacity communications. Satellites are vital for supporting mobile military forces and providing assured connectivity for nuclear forces. Threats to cables and satellites have only proliferated.

In February 2023 two cables were cut connecting Taiwan with the Matsu Islands, leaving its 14,000 inhabitants without internet access. Cable cutting is a ‘gray zone’ activity, because it allows states to interfere with critical telecommunications infrastructure without rising to the level of general conflict. Just like in the cyber realm, attributing cable cutting and establishing whether it was intentional can be exceptionally difficult.

This 2023 Taiwan incident is only a small preview of the potential consequences of large-scale cable cutting in the lead up to a conflict involving the United States and China.

Telecommunications networks constitute the ‘soft underbelly’ of the American war machine and are therefore key targets for its adversaries. The challenge is not solely military in nature. Severing undersea cables would have spillover effects, since they form the global information backbone. Consequently, strengthening their security is vital from a ‘whole of society’ perspective.

Investing in more undersea cable routes and increasing the number of cable-laying vessels are both necessary for the United States to improve the resilience of its telecommunications infrastructure. Emerging satellite communications constellations cannot alone solve the cable security problem, but they are an important part of the solution.

At the same time the unanswered question still hangs in the air - who blew up the Nord Stream gas pipelines? The West is “modestly silent” stating it still does not know…

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:48 13.05.2024 •

11:48 13.05.2024 •