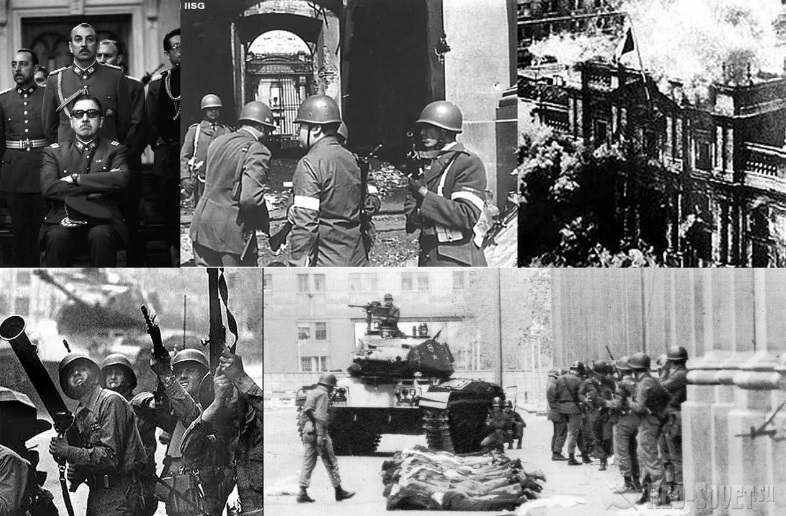

Bombing of the La Moneda Presidential Palace on September 11, 1973 in Santiago de Chile.

“In the Eisenhower period, we would be heroes,” Henry Kissinger told President Richard Nixon several days after the overthrow of Salvador Allende in Chile, lamenting that they would not receive credit in the press for this Cold War accomplishment.

Fifty years later, as Chileans and the world commemorate the anniversary of the U.S.-backed military takeover that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power, a fierce debate over the extent of the U.S. contribution to the coup continues. On September 6, a leading Chilean television channel, Chilevision, broadcast a major documentary film titled “Operation Chile: Top Secret,” featuring dozens of U.S. declassified records obtained by the National Security Archive’s Chile Documentation Project, including recently obtained documents published in the new Chilean edition of Archive analyst Peter Kornbluh’s book, “Pinochet Desclasificado.”

On the eve of the 50th anniversary, the Archive is posting an edited section of Kornbluh’s book “The Pinochet File” on the “Countdown Toward the Coup.” The essay records U.S. government actions, internal debates and policy deliberations as conditions for the coup evolved between March and September 1973.

The Chile’s people stood up for the socialist president Allende, and the Americans really didn’t like it.

The Chile’s people stood up for the socialist president Allende, and the Americans really didn’t like it.

On September 12, 1973, a day after the Chilean military violently took power, State Department officials met to discuss press guidelines for Henry Kissinger on “how much advance notice we had on the coup.” Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs Jack Kubisch noted that one Chilean military official had told the embassy that the plotters had withheld from their U.S. supporters the exact date they would move against Allende. But Kubisch said he “doubted if Dr. Kissinger would use this information, for it would reveal our close contact with coup leaders.”

In the months leading up to the coup, the CIA and the Pentagon had extensive contacts with Chilean plotters through various assets and agents and at least three days’ advance knowledge of a concrete date for a military takeover.

On April 10, the Western Hemisphere division did secure the approval from CIA director James Schlesinger for “accelerated efforts against the military target.” These covert actions, according to a May 7 memorandum to Schlesinger from WH division chief Theodore Shackley, were “designed to better monitor any coup plotting and to bring our influence to bear on key military commanders so that they might play a decisive role on the side of the coup forces when and if the Chilean military decides on its own to act against Allende.” Headquarters authorized the Santiago Station “to move ahead against military target in terms of developing additional sources” and promised to seek appropriations for an expanded military program when “we have much more solid evidence that military is prepared to act and has reasonable chance of succeeding.”

The Chilean high command provided evidence that the military was not yet ready to act on June 29, when several rogue units of the Chilean armed forces deployed to take over the presidential palace known as La Moneda. In his secret “Sit Rep # 1” for President Nixon, Kissinger reported that Chilean army units had “launched an attempted coup against the government of Salvadore Allende.”

One report noted that military plotters had chosen July 7 as the “target date” for another coup attempt, but the date was now being postponed because of the opposition of Commander in Chief Carlos Prats, as well as the difficulty in lining up “the key Army regiments in the Santiago area.”

The CIA also reported that the military was attempting to coordinate its takeover with the Truck Owners Federation, which was about to initiate a massive truckers strike. The violent strike, which paralyzed the country throughout the month of August, became a key factor in creating the coup climate the CIA had long sought in Chile. Other factors included the decision by the leadership of the Christian Democrats to abandon negotiations with the Popular Unity government and to work, instead, toward a military coup. In a CIA “progress report” dated in early July, the Station noted “there has been increasing acceptance of the part of PDC leaders that a military coup of intervention is probably essential to prevent a complete Marxist takeover in Chile. While PDC leaders do not openly concede that their political decisions and tactics are intended to create the circumstances to provoke military intervention, Station [covert] assets report that privately this is generally accepted political fact.” The Christian Democrat position, in turn, prompted the traditionally moderate Chilean Communist Party to conclude that political accommodation with the mainstream opposition was no longer feasible and to adopt a more militant position, creating deep divisions with Allende’s own coalition. The military’s hardline refusal to accept Allende’s offer of certain cabinet posts also accelerated political tensions. “The feeling that something must be done seems to be spreading,” CIA headquarters observed in an analytical report on “Consequences of a Military Coup in Chile.”

The resignation of Commander-in-Chief Carlos Prats in late August after an intense public smear campaign led by El Mercurio and the Chilean right wing eliminated the final obstacle for a successful coup. Like his predecessor, General Schneider, Prats had upheld the constitutional role of the Chilean military, blocking younger officers who wanted to intervene in Chile’s political process. In an August 25 intelligence report stamped “TOP SECRET UMBRA,” the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) noted that the departure of Prats “has removed the main factor mitigating against a coup.” On August 31, U.S. military sources within the Chilean army were reporting that “the army is united behind a coup, and key Santiago regimental commanders have pledged their support. Efforts are said to be underway to complete coordination among the three services, but no date has been set for a coup attempt.”

By then, the Chilean military had established a “special coordination team” made up of three representatives of each of the services and carefully selected right-wing civilians. In a series of secret meetings on September 1 and 2, this team presented a completed plan for overthrowing the Allende government to heads of the Chilean army, air force, and navy. The incipient Junta approved the plan and set September 10 as the target date for the coup. According to a review of coup plotting obtained by the CIA, the general who replaced Carlos Prats as commander-in-chief, General Augusto Pinochet, was “chosen to be head of the group” and would determine the hour for the coup to begin.

On September 8, both the CIA and the DIA alerted Washington that a coup was imminent and confirmed the date of September 10. A DIA intelligence summary stamped TOP SECRET UMBRA reported that “the three services have reportedly agreed to move against the government on 10 September, and civilian terrorist and right-wing groups will allegedly support the effort.” The CIA reported that the Chilean navy would “initiate a move to overthrow the government” at 8:30 A.M. on September 10th and that Pinochet “has said that the army will not oppose the navy’s action.”

On September 9, the Station updated its coup countdown. A member of the CIA’s covert agent team in Santiago, Jack Devine, received a call from an asset who was fleeing the country. “It is going to happen on the eleventh,” as Devine recalled the conversation. His report, distributed to Langley headquarters on September 10, stated:

A coup attempt will be initiated on 11 September. All three branches of the Armed Forces and the Carabineros are involved in this action. A declaration will be read on Radio Agricultura at 7 A.M. on 11 September. The Carabineros have the responsibility of seizing President Salvador Allende.

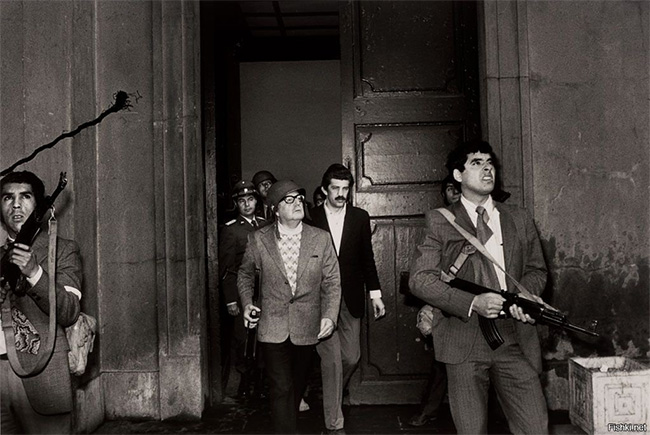

President Salvador Allende. The last combat…

President Salvador Allende. The last combat…

By 8:00 A.M. on September 11, the Chilean navy had secured the port town of Valparaiso and announced that the Popular Unity government was being overthrown. In Santiago, Carabinero forces were supposed to detain President Allende at his residence, but he managed to make his way to La Moneda, Chile’s White House, and began broadcasting radio messages for “workers and students” to come “and defend your government against the armed forces.” As army tanks surrounded La Moneda firing on its walls, Hunter Hawker jets launched a pinpoint rocket attack on Allende’s offices at around noon, killing many of his guards. Another aerial strafing attack accompanied the military’s ground effort to take the inner courtyard of the Moneda at 1:30 P.M.

During the fighting, the military repeatedly demanded that President Allende surrender and made a perfunctory offer to fly him and his family out of the country. In a now famous audiotape of General Pinochet issuing instructions to his troops via radio communications on September 11, he is heard to laugh and swear “that plane will never land.” Forecasting the savagery of his regime, Pinochet added: “Kill the bitch and you eliminate the litter.” Salvador Allende was found dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in his inner office around 2:00 P.M. At 2:30 P.M., the armed forces radio network broadcast an announcement that La Moneda had “surrendered” and that the entire country was under military control.

By the most narrow definition of “direct role” — providing planning, equipment, strategic support, and guarantees — the CIA does not appear to have been involved in the violent actions of the Chilean military on September 11, 1973. The Nixon White House sought, supported, and embraced the coup, but the political risks of direct engagement simply outweighed any actual necessity for its success. The Chilean military, however, had no doubts about the U.S. position. “We were not in on planning,” recalled CIA operative Donald Winters. “But our contacts with the military let them know where we stood — that was we were not terribly happy with [the Allende] government.”

The CIA and other sectors of the U.S. government, moreover, were directly involved in operations designed to create a “coup climate” in which the overthrow of Chilean democracy could and would take place. Colby’s memo appeared to omit the CIA’s military deception project, the covert black propaganda efforts to sow dissent within the Popular Unity coalition, the support to extremist elements such as Patria y Libertad, and the inflammatory achievements of the El Mercurio project, which agency records credited with playing “a significant role in setting the stage” for the coup — let alone the destabilizing impact of the invisible economic blockade. The argument that these operations were intended to preserve Chile’s democratic institutions was a public relations ploy contradicted by the weight of the historical record. Indeed, the massive support that the CIA provided to the ostensible leading representatives of Chilean democracy — the Christian Democrats, the National Party, and El Mercurio — facilitated their transformation into leading actors in, and key supporters of, the Chilean military’s violent termination of Chile’s democratic processes.

“Our policy on Allende worked very well,” Assistant Secretary Kubisch commented to Kissinger on the day after the coup. Indeed, in September of 1973, the Nixon administration had achieved Kissinger’s goal, enunciated in the fall of 1970, to create conditions which would lead to Allende’s collapse or overthrow. At the first meeting of the Washington Special Actions Group, held on the morning of September 12 to discuss how to assist the new military regime in Chile, Kissinger joked that “the President is worried that we might want to send someone to Allende’s funeral. I said I did not believe we were considering that.” “No,” an aide responded, “not unless you want to go.”

On September 16, President Nixon called Kissinger for an update; their conversation was recorded by Kissinger’s secret taping system. The two candidly discussed the U.S. role. Nixon seemed concerned that the U.S. intervention in Chile might be exposed. “Well we didn’t — as you know — our hand doesn’t show on this one though,” the president noted. “We didn’t do it,” Kissinger responded, referring to the issue of a direct involvement in the September 11 coup. “I mean we helped them. [Omitted word] created the conditions as great as possible.” “That is right,” Nixon agreed.

Nixon and Kissinger commiserated over the fact that they wouldn’t receive laudatory credit in the media for Allende’s demise. “The Chile thing is getting consolidated,” Kissinger reported, “and of course the newspapers are bleating because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.” “Isn’t that something,” Nixon said, excoriating the “liberal crap” in the media. Kissinger suggested that the press should be “celebrating” the military coup. “In the Eisenhower period,” Kissinger told Nixon, “we would be heroes.”

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:07 11.09.2023 •

12:07 11.09.2023 •