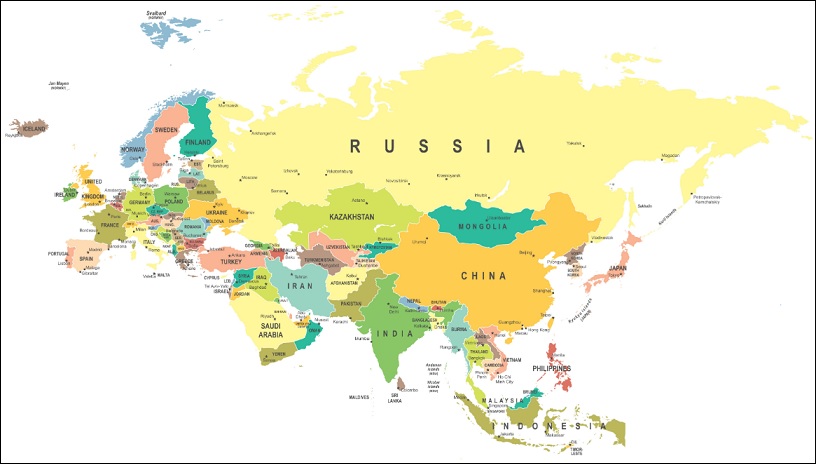

In a big and detailed article the ‘Foreign Policy’ analyzes the new balance of power in Eurasia (map). There is a lot of propaganda that “America is strong”, but the issue and the above analysis indicate that the United States understood – their dominance on the Big Island, as the Anglo-Saxons call Eurasia, was under attack by the joint forces of the countries of the vast continent, which no longer wants to live under military-political and financial-economic control of Washington. And despite all the bravado of the author of the magazine, he understands that the fading United States will be forced to leave Eurasia for good, otherwise they will simply be thrown out.

Here are the highlights of ‘The Battle for Eurasia’ article:

…All the great conflicts of the modern era have been contests over Eurasia, where dueling coalitions have clashed for dominance of that supercontinent and its surrounding oceans. Indeed, the American Century has been the Eurasian Century: Washington’s vital task as a superpower has been keeping the world in balance by keeping Eurasia divided. Now the United States is again leading a coalition of democratic allies on Eurasia’s margins against a group of centrally located rivals — while crucial swing states maneuver for advantage.

Countries such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and India have a critical role in this era of rivalry, thanks to the geography they occupy and the clout they wield. In many cases, these powers are determined to play both sides. Containing the Eurasian challenge will involve strengthening the bonds within and between the United States’ alliance networks. Yet what makes the current moment so daunting is that opportunistic swing states will also shape the fight between Fortress Eurasia and the free world.

Eurasia has long been the world’s key strategic shatter zone because it is where the richest and most powerful countries — the United States excepted — are located. And since the early 20th century, this sprawling supercontinent has seen vicious brawls for geopolitical primacy.

The specifics change, but the basic clash — between those who seek to rule Eurasia and those, including the overseas superpower, who oppose them — endures.

After their Cold War victory, Washington and its friends were preeminent in all of Eurasia’s key subregions: Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East. Yet challenges have since reemerged from rivals that have increasingly coalesced around their shared hostility to the status quo. And just as major crises often speed up history, the Russia-Ukraine war is accelerating the rise of a new Eurasian bloc.

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea all seek to overturn the balance of power and view the United States as the main obstacle.

Democracies in Asia have supported Ukraine and sanctioned Russia for fear that successful aggression in one region may encourage deadly adventures in others. Countries linked by liberal values and support for the U.S.-led international order are strengthening their defenses from Eastern Europe to the Western Pacific, and they are rethinking economic and technological ties to the tyrannies in Moscow and Beijing. What U.S. President Joe Biden calls the “free world” is again taking shape. So, unfortunately, is an autocratic coalition.

All are located within Eurasia and enjoy proximity, if not contiguity, with at least one other revisionist state. As the Russia-Ukraine war heightens global tensions, these autocracies are drawing together, for self-protection and strategic profit.

A Eurasian bloc is cohering militarily, as the war fosters overlapping and increasingly ambitious defense ties. Russia’s military relationship with North Korea has become a two-way street, as Pyongyang sells Moscow badly needed artillery ammunition. Russia and Iran, meanwhile, are building what CIA Director William Burns calls a “full-fledged defense partnership.” That partnership involves transfers of drones, artillery, and, reportedly, missiles that have strengthened Russia on battlefields in Ukraine; it may presage the transfer of advanced Su-35 fighter aircraft, air defense systems, or ballistic missile technology, which would make Tehran a tougher enemy for the United States and Israel.

China, for its part, hasn’t openly supported Putin’s war with lethal military aid, for fear of U.S. and European sanctions. It has, however, provided so-called nonlethal assistance — from drones to computer chips — that helps Putin protract his fight, and Beijing would probably go further if its most important ally were facing defeat. For now, the conspicuous presence of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s defense experts during his recent summit with Putin in Moscow signaled that the larger military relationship — which already features joint exercises, arms sales, and significant technological cooperation — continues to race past the limits many Western observers expected a decade ago.

It wouldn’t take a formal Sino-Russian alliance to upend the military balance. If Russia provides China with sensitive submarine-quieting technology or surface-to-air missiles, it could profoundly change the complexion of a Sino-American war in the Western Pacific. In today’s Eurasia, well-armed revisionists are making common cause.

They are also restructuring international trade. Commerce, or weapons shipments, that traverses Eurasia’s marginal seas can be seized by globe-ranging navies. Dollar-dependent economies are vulnerable to U.S. sanctions. A second aspect of Fortress Eurasia, then, involves building trade and transportation networks safe from democratic interdiction.

For years, China has invested in overland pipelines and railroads meant to ensure access to Middle Eastern oil and other crucial resources. Beijing is now seeking to sanction-proof its economy by reducing reliance on foreign inputs, a project that has gained urgency thanks to the Western economic war on Moscow. Russia and Iran are energizing the International North-South Transport Corridor, which connects the two countries via the land-locked Caspian Sea, as Tehran instructs Moscow in sanctions evasion. Likewise, Russia and China are deepening cooperation to develop the Northern Sea Route, the least vulnerable maritime path between China’s Pacific ports and European Russia.

Russia-Iran trade has spiked since February 2022, while China has become Moscow’s key commercial partner “by a wide margin,”. Bilateral trade in Russian oil and Chinese computer chips is surging; Russian firms are turning to Hong Kong to raise capital while skirting sanctions. And as Chinese technology spreads throughout Eurasia, its currency proliferates, too.

This February, the yuan overtook the dollar as the most traded currency on the Moscow Exchange. China and Iran are also experimenting with cutting the dollar out of bilateral trade.

Eurasian integration will make Washington’s antagonists less vulnerable to sanctions and strengthen them militarily.

Finally, this Eurasian bloc is cohering intellectually and ideologically. The Sino-Russian joint statement in February 2022 portrayed the two countries as defending their autocratic political systems while resisting the United States’ Cold War-style alliance blocs. Iranian officials describe Eurasian cooperation as the antidote to U.S. “unilateralism”; Putin deems Eurasia a haven for “traditional values” besieged by Western “neoliberal elites.” Because the current war has severed Putin from the West, it has also resolved Russia’s perennial debate about which direction to face. For the time being, Russia’s destiny is Eurasian.

Eurasian integration will also make the United States’ antagonists less vulnerable to sanctions. It will strengthen them militarily against their foes. It will lead to wide-ranging diplomatic cooperation — such as stronger Russian support for China’s position on Taiwan — or perhaps even material assistance to one another in a war against the United States. If Russia had the opportunity to help China bleed the United States in a fight in East Asia, does anyone doubt it would have the motivation?

Even short of that, Fortress Eurasia will make the world safer for violent revisionism. The more secure these countries feel in their Eurasian stronghold, the more support they have from one another, the more emboldened they will be to project power into peripheral regions — the Western Pacific, Europe, the Middle East — and beyond, writes ‘The Foreign Policy’.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

12:03 19.06.2023 •

12:03 19.06.2023 •