While German authorities draw up a list of bunkers while simultaneously provoking Russia by arming Ukraine, the real panic in the country is in the economy, especially as German industrial giants continue to lay off tens of thousands of workers. Yet, despite the economic calamity, Berlin is still not considering the removal of sanctions on Russia, which is the main reason why energy prices in Germany have spiked, notes Ahmed Adel, Cairo-based geopolitics and political economy researcher.

At the end of October, Volkswagen announced that it would close at least three factories in Germany and reduce the number of employees in the remaining ones. In total, tens of thousands will lose their jobs at Volkswagen alone, with the wages of those remaining reduced.

The steel giant Thyssen Krupp in the coming years will lay off up to 11,000 people, or as much as 40% of the workforce, according to the Financial Times. There will be 30,000 layoffs at Deutsche Bahn (German Railways); 14,000 at ZF Friedrichshafen, a manufacturer of auto parts; 14,000 at Continental tyres; 13,000 at SAP; and thousands more at Bosch, Audi, and elsewhere.

It is predicted that about 140,000 jobs will disappear in the German auto industry alone in the next ten years. State television reports that the steel industry will be much smaller and, despite being greener, significantly more expensive by 2030.

But it is not only a question of years in the future but today. Until the extraordinary parliamentary elections, scheduled for February 23, thousands of workers are expected to lose their jobs every month — at least 15,000 until the elections—and as many as 80,000 during the next year.

Another disheartening forecast by the president of the Metal Industry Association, Stefan Wolff, is that 300,000 workers will be out of work in the metal industry by 2030.

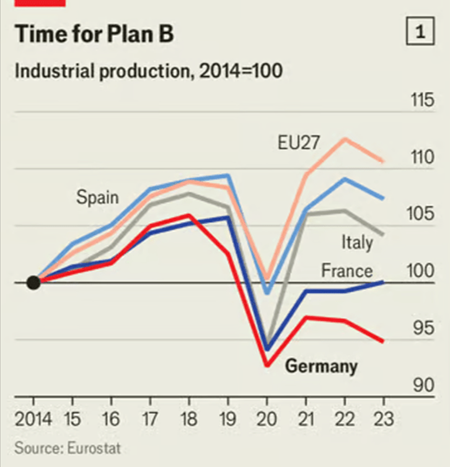

With this context, it is unsurprising that The Economist magazine has plenty of good reasons to state, “Once dominant, Germany is now desperate” and that “its business model is breaking down.”

“The country is gripped by fears of deindustrialization as it heads into an election that seems certain to throw its chancellor, Olaf Scholz, out of his job if his party does not dump him first,” added the magazine.

“For years they had this belief that ‘We are the best,’ and suddenly it's over,” commented an EU official with a noticeable tone of malice.

One of the more important reasons for such a decline is the high energy prices due to cutting ties with Russia. The cry of the CEO of ThyssenKrupp that Germany is in the middle of deindustrialization is reminiscent of when the European Nonferrous Metallurgy Association two years ago sent an urgent call to the head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, to prevent permanent deindustrialization due to rising electricity and gas prices, with the important note that whatever happens, closed tends to stay permanently closed.

And there is, of course, the unsolvable enigma of competition from China, which, for example, was an importer of cars in 2020, while last year it became the world’s largest exporter of not only cars but also machines and the chemical industry.

The Financial Times revealed how much the innovation-industrial world order has turned upside down compared to what was prevailing. Now, the EU demands technology transfer from Chinese companies that would like to work on its soil.

Of course, this rapid deindustrialization of Germany was sparked by the boomeranged effects of anti-Russian sanctions, which, instead of collapsing the Russian economy and ending the special military operation, brought German industry to a standstill as energy prices skyrocketed and deepened the cost-of-living crisis. Yet, this is a reality that Berlin refuses to acknowledge, even to the detriment of its major industries.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:53 12.12.2024 •

10:53 12.12.2024 •