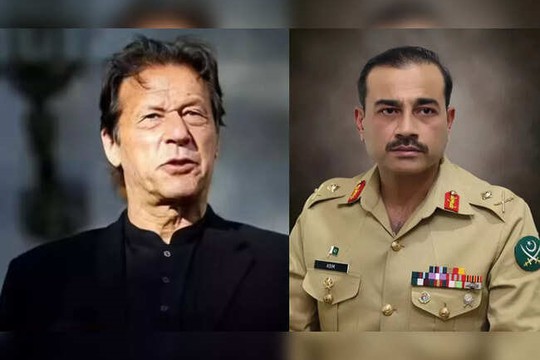

Imran Khan & Asim Munir (R)

Photo: ‘India Times’

Rumors of Imran Khan's death in custody, denied by authorities, highlight a power shift favoring the military. A constitutional amendment grants Army Chief Asim Munir extensive authority, echoing past dictatorships and fueling fears of political silencing, reminiscent of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's fate, writes ‘The Economic Times’.

The latest wave of rumours surrounding former Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan’s alleged death in custody, refuted by the jail authorities, has more to it than a routine misinformation campaign. A new balance of power that tilts towards the military brings back fears from the past.

The conjectures over Khan’s well-being do not exist in a vacuum. Recently, Pakistan has seen a major power shift, with the military’s influence set to override the civil authorities as army chief Asim Munir has pulled off a silent coup through a constitutional amendment that gives him almost as much power as earlier military dictators had grabbed through coups.

The anatomy of a rumour

Claims that Imran Khan had died in custody, circulated by dubious online sources and amplified by social media, were categorically denied by prison officials, who insisted he remains in good health. Officials dismissed the allegations as fictional, and Defence Minister Khawaja Asif even argued that Khan enjoys unusually comfortable conditions in detention. Yet the rumours spread with unchecked virality.

Several factors are behind this. Khan has faced tightly restricted access to family members since August 2023, and the recent brutal police handling of his three sisters during their attempt to meet him outside Adiala Jail only deepened the sense of opacity. When access is blocked and information flows are constricted, rumours are likely to spread. In Pakistan, where the state’s relationship with political detainees has often been shrouded in secrecy, the emergence of such rumours felt almost predictable.

But the deeper reason lies in the nation's memory of its turbulent past. Pakistanis have witnessed abrupt political disappearances, sudden deaths in custody and manipulated narratives during previous eras of dictatorship. This past creates an environment in which rumours such as Khan's death in custody are readily believed.

The return of military dictatorship by other means

The timing of the rumours is inseparable from a constitutional shift unfolding in Pakistan. The 27th Constitutional Amendment, rushed through parliament within days, has changed the balance of power in Pakistan. By placing General Asim Munir at the apex of the army, navy and air force as the country’s first Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), the amendment creates a military office with sweeping authority that matches and even surpasses the role civilian institutions historically held.

The shift of overall control of the tri-services from the president and cabinet to the CDF marks a fundamental departure from Pakistan’s previous constitutional design. The grant of field marshal rank, lifelong immunity and legal protections comparable to those of the president elevate Munir to a stature rarely seen in modern democratic systems. Critics argue that no parallel exists for such a concentration of military power within a constitutional framework.

When Khan became prime minister in 2018, he appointed Munir as Director-General of the ISI. Only months later, Munir was removed from the post, reportedly after he presented corruption findings involving Khan’s wife. This marked the beginning of a strained relationship. When Munir rose to the position of army chief in 2022, tensions deepened further, with Khan openly accusing him of engineering political cases against him and targeting him through state institutions. In this context, Munir accumulating more power must be concerning for Khan's followers.

The memory of Bhutto haunts Pakistan

The rumours about Khan’s death align with events Pakistanis have seen before. In 1977, prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was overthrown by army chief Zia-ul-Haq. Bhutto was jailed and eventually executed after a trial which was later declared unfair by the Supreme Court. Musharraf’s rise in 1999, too, brought an era of centralised military control that sidelined civilian leadership. The coup by Musharraf had led to imprisonment of Nawaz Sharif who was allowed to escape to the UK later, thus avoiding the fate of his predecessor Bhutto.

Munir’s ascent to unprecedented power is different in form but similar in effect. Unlike Ayub Khan, Zia-ul-Haq or Musharraf, who seized power through coups and imposed martial law, Munir’s authority has emerged through constitutional amendments supported by a pliant parliament. Thus, democratic processes have been used to create an arrangement similar to past military dictatorships.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:28 28.11.2025 •

11:28 28.11.2025 •