Pic.: brightspotcdn

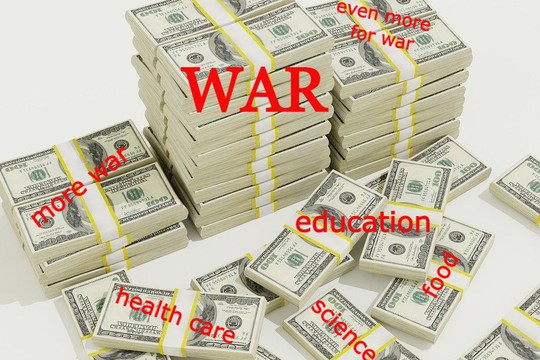

“There is no way of defending the continent without cuts to social spending,” – in that rare thing, an Angela Merkel statement that aged well, the long-serving German chancellor worried that Europe accounted for 7 per cent of the world’s population, a quarter of its economic output and half of its social spending. Those numbers have modulated somewhat in the subsequent 13 years, but the gist of her point holds, ‘The Financial Times’ notes.

More than that, it has gained a new urgency. The reason Merkel wanted some welfare trimmings was to preserve Europe’s “way of life”. The mission now is to defend Europe’s lives. How, if not through a smaller welfare state, is a better-armed continent to be funded?

Borrowing? Britain and France have had tense moments with bond investors of late. Public debt nears or exceeds national output in both countries, as it does in Italy. One way around this might be some Europeanisation of debt. Imagine a pact in which, in effect, Germany borrows more to defray the costs of military build-up in other countries, which in turn can do things — build nuclear weapons, post troops near Russia — that might be too taboo for Berlin to do itself. The trouble is that just describing this grand bargain in words makes one wince at the profound unlikelihood of it, at least in the short term.

The other option is to raise taxes. At the margins, this could happen. But big rises? In an already undynamic continent? It would show that Europe has learnt nothing from decades of economic torpor, or from endless competitiveness reports, or from America. It isn’t even clear that tax increases are more saleable to the electorate than spending cuts. In Britain, a government with a huge mandate hasn’t entirely recovered from autumn’s tax-raising Budget, even though its brunt fell mostly on business. Twice, Emmanuel Macron has incurred protests that shook the French state. The first was against a tax rise.

Anyone under 80 who has spent their life in Europe can be excused for regarding a giant welfare state as the natural way of things. In truth, it was the product of strange historical circumstances, which prevailed in the second half of the 20th century and no longer do. One was the implicit American subsidy through Nato, which allowed European governments to spend a certain amount on butter that might otherwise have gone on guns. (Though plenty was spent on both.) Another was the fact that, during the welfarist golden age, Europe had little competition from China or even India, which didn’t really plug into the world economy until the 1990s. The “social market” was nurtured in a cocoon.

Yet a third helpful factor was a youngish population — 13 per cent of Brits were over 65 in 1972. Now around a fifth are. The numbers for France are similar, and Germany’s a tad higher, with all three countries projected to age a lot more as the century wears on. These pension and healthcare liabilities were going to be hard enough for the working population to meet even before the current defence shock. Now, they are scarcely plausible, to say nothing of the moral spectacle of the young being asked to bear arms and keep the old in a certain style. This is more than even Lord Kitchener asked. Governments will have to be stingier with the old. Or, if that is unthinkable given their voting weight, the blade will have to fall on more productive areas of spending.

Either way, the welfare state as we have known it must retreat somewhat: not enough that we will no longer call it by that name, but enough to hurt.

The question is – whether the public agrees?

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:23 11.03.2025 •

11:23 11.03.2025 •