Pic.: The Times Of India

The Russian economy has shown solid growth in many sectors while unemployment remains at a record low, prompting officials to hint at a brighter outlook for the year despite Western sanctions over the war in Ukraine, writes Reuters with great surprise.

Driven by military production, industrial output rose by 3.3% in July compared with a 2.7% increase the previous month, and by 4.8% since the start of the year, compared with 3.1% growth in the same period in 2023.

A preliminary estimate for gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the first half of the year stood at 4.6%, compared with 1.8% for the same period last year.

Officials attributed this growth to strong capital investment, including by the private sector, which in the second quarter rose by 8.3% year-on-year to 8.44 trillion roubles ($92 billion), following 14.5% growth in the first quarter of the year.

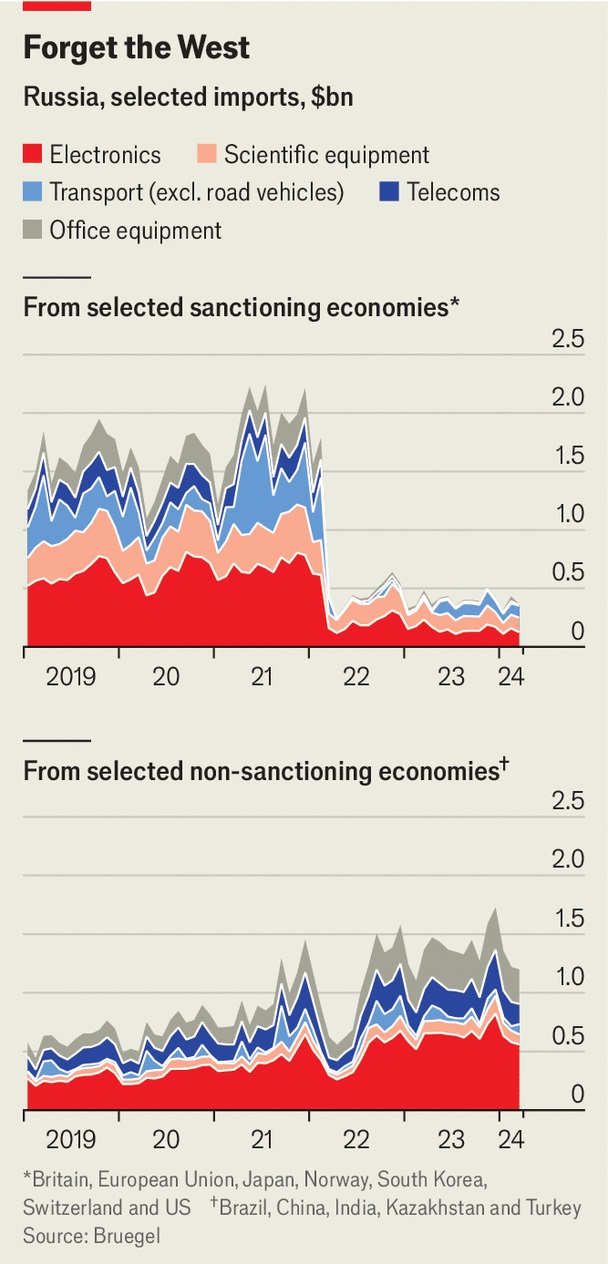

The data suggested the economy was holding up despite Western economic sanctions and problems with international payments with Russia's major trading partners, such as China, which led to a 9% fall in overall imports in the first half of the year.

However, they also pointed to overheating, which forced the central bank to hike its benchmark interest rate by 200 basis points to 18% in July, the highest level in more than two years.

In the first half of the year, real wages grew by 9.4%, while nominal wages increased by 18.1% compared with the same period in 2023, according to the new data. Unemployment remained at a historically low level of 1.9 million people in July, or 2.4% of the workforce.

Chart: The Economist

Chart: The Economist

Over the next decade, the Russian state expects to funnel $70bn into the construction of transport routes to connect the country to trade partners in Asia and the Middle East. Russia’s far east and high north will receive the lion’s share; a smaller sum will go on the International North-South Transport Corridor, a project designed to link Russia and the Indian Ocean via Iran. Officials promise growth in traffic along all non-Western trade routes, writes ‘The Economist’.

Countries that have not signed up to sanctions, led by China and India, have replaced lost trade with the West. As patchy infrastructure in Russia’s east limits exports to Asia, goods often have to go by a circuitous route, through Black Sea and Baltic ports, and via the Suez Canal. Russian officials worry about blockages on the route, and that nato‘s sway over crucial arteries, such as the Bosporus, could permit extra trade restrictions. In a bid to boost exports and shield commercial ties from interference, Russia is therefore investing in connections with friendlier countries. New links “should become an example of the broadest international co-operation”, Mr Putin proclaims.

This represents a striking change of approach. Russia once shied away from building infrastructure links with China and Iran, as European commerce was lucrative enough. The war has changed its calculations. Trade between Russia and China — boosted by Chinese demand for Russian oil — reached a record of $240bn last year, up by two-thirds since 2021. The first rail bridge across the Amur River, Russia’s natural border with China, opened in 2022. Another was given the go-ahead last year. Russia wants to lift cargo volumes on the Northern Sea Route, a shipping lane that runs along its Arctic shore to eastern China, from 36m to 200m tonnes by 2030.

Until a couple of years ago, Russian firms also eschewed Iran for fear of Western sanctions. Now the two outcasts are pursuing the instc with renewed vigour. Last year Russia agreed to finance Iran’s Rasht-Astara railway, a missing 162km leg of the corridor’s western prong, construction of which had stalled despite having been approved almost two decades ago. Mr Putin says that, once complete, the instc will “significantly diversify global traffic flows” by transforming Iran into an outlet for Russian goods heading for the Middle East, Asia and farther afield. India is the ultimate prize. Unlike China, its demand for coal and oil is projected to remain strong until at least 2030.

Decades of neglect have left ports and railways in eastern Russia in desperate need of repair. Will there be sufficient funding for the job? More from elsewhere would help. In May India signed a ten-year contract, worth $370m, to extend its control over Iran’s Chabahar Port. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are upgrading domestic rail and road infrastructure to help the instc. But Russia and Iran remain the corridor’s main funders. In 2022 they accounted for 68% of investment in the route — and cash-strapped Iran relies on Russian loans for its share. Mr Putin plans are – to spend heavily on infrastructure.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:39 01.09.2024 •

10:39 01.09.2024 •