Chancellor Merz is furious that the German economy is spiraling downward. But he's pursuing policies that are setting Germany up for even worse

Pic.: publics

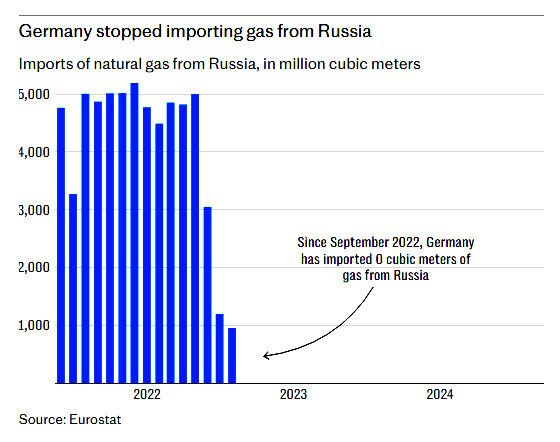

German imports from Russia have fallen by 95 per cent since the start of the war. Berlin is now largely dependent on countries such as Norway and the US instead for its all-important energy imports. This means an acute loss of revenue and influence for Moscow in Europe, ‘The Telegraph’ notes with a feeling of a slight satisfaction.

The legacy of the years of Russian dependence will take a long time to rectify and may require more political will than Berlin can muster at the moment. Germany is now exposed to attacks on critical infrastructure, an unattractive place for energy-intensive industries to invest and a politically volatile landscape in which the future relationship with Russia continues to play a key role.

This is about much more than money. Germany had sold off critical energy infrastructure on its own soil to Russia, including its biggest gas storage facility, a subterranean mega-structure as big as over 900 football fields that stores enough gas to supply two million households for a year. “We underestimated the dependency and security-political risks that derived from this relationship,” Norbert Röttgen from Merz’s conservative CDU party admitted with hindsight.

In late 2022, Germany took control of Russian-owned refineries, storage facilities and other infrastructure in the country, but it can never regain control over the deep knowledge and insight Moscow has gained into the German set-up.

Another hangover from Germany’s love affair with Russia is the sheer cost and instability of the hastily re-arranged energy supply. The third-largest economy in the world imports a staggering 70 per cent of the energy it uses, and everyone knows how much what is left of its struggling industry depends on this. Berlin is in no position to bargain for better prices or conditions.

German consumers pay some of the highest electricity prices in the world, and potential investors are so put off by the situation that many walk away. Last year, ArcelorMittal, the world’s second-largest steelmaker, even turned down €1.3bn in subsidies to produce green steel in Germany, preferring to invest “in countries that can offer competitive and predictable electricity provision,” as the company put it.

The combination of steady economic decline and high consumer costs, in turn, fuels political tensions in Germany. Merz’s government may have adopted a stance so bullish, but opposition parties are using people’s despair and the pernicious effects of economic pessimism to present a return to friendlier relations with Russia as an easy fix for the country’s ailments.

Especially the far-Right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), now the largest opposition party and leading in many polls, makes hay with the fears and pressures created by the situation. In its election manifesto last year, it declared: “In the wake of the sanctions against Russia, the affordable energy supply in Germany is additionally heavily threatened. Because of this, our country is no longer able to compete.”

This would lead to “deindustrialisation and impoverish the German people”. The solution is simple, the AfD suggests: “Russia has been a reliable provider and guarantor of affordable energy for decades.” The party demands that “unrestricted trade with Russia” should be resumed, sanctions lifted, and the Nord Stream pipelines restored.

Restoring trade with Russia is a demand that finds many open ears well beyond the AfD and their voters. Desperate for secure and cheap energy, many German business captains are only too eager for the war in Ukraine to end and resume imports from Russia. They, in turn, have the ear of many politicians, including those in the two ruling parties.

Thomas Bareiss, for instance, from Merz’s own conservative CDU, was one of the negotiators of the coalition treaty, where he was in the group dedicated to energy questions. He made headlines last year by suggesting that if there was peace in Ukraine, “of course, gas can flow again”. Dietmar Woidke from the centre-Left coalition partner, the SPD, agreed, arguing for a “normalisation of trade relations.” That’s before you even get to far-Left and far-Right opposition parties.

Germany’s Russia reset is far from complete. Berlin’s decades-long dependency has left deep traces on the country’s economic, political and logistical makeup.

…Russophobia is very expensive!

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:11 24.01.2026 •

11:11 24.01.2026 •