European Union Force (EUFOR).

Pic.: ‘The New European’

Imagine a world in which western Europe was actually able to stick it to Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump simultaneously. As if. Back in the real world, there’s a remote possibility the Europeans might get their act together sufficiently to stand up to one, or the other. But not both. They will, in classic fashion, be split, notes British ‘UnHerd’.

Some of the eastern European countries, the Baltic States, for example, will prioritise a push-back against Russia. Others, like France, are more concerned with driving their independence from the US. Then there is a third group that wants neither.

France, the only nuclear power in the EU, doesn’t have sufficient capacity to provide the scale of defence services to other members of the EU that the US has been willing to do until now.

So, where does that leave Europe? What they are agreed on is the plan is to increase military spending. The EU will follow Germany’s example and partially exempt the defence budget from the fiscal rules. But the truth is, no amount of investment will wean the EU off its American dependency any time soon. It will take decades to close the immense defence technology gap.

To build entire industries from scratch takes time. You need defence companies, supply chains, and know-how. Europe is far from the cutting edge of 21st century defence technology and its expertise in that sector has been diminished since the end of the Cold War.

A graphic example of what happens when you lose industrial know-how can be seen in the civilian nuclear sector. Germany used to build the best nuclear power stations in the world but had changed by 2023 when it closed the last of its own plants. That same year, the country only had eight professors active in nuclear research — there were, by way of comparison, 173 professors in gender studies. This is what happens when you drive down industries. They can’t just be switched back on.

The same applies for defence. The US is miles ahead of us thanks to decades of investment into digital-era technologies. From the Manhattan Project onwards, American military investment and innovation has pioneered civilian spin-offs: the transistor in 1947, the integrated circuit a decade later, and the communication technologies in the Sixties that morphed into the technology behind the internet.

When the US was investing in AI, the Europeans were fussing over the Green Deal. We spent our peace dividend on social transfers. As a result, the German military still uses the fax machine and we are similarly in the dark ages when it comes to building ballistic missiles, AI-powered satellites, and electronic warfare.

It is laughable, then, to think we could possibly match Russia’s defence capabilities in the next five years. Even with investment in place, given the weakness of our industry, we would have to spend it on defence imports from the US. At which point, action is thwarted by Europe’s age-old problem. Politics.

There are no indications that political majorities in Berlin or Paris are willing to trade off welfare spending to pay for US arms imports. Italy and Spain are already recusing themselves from re-militarisation because they are far away from Russia, and because they have much less fiscal scope.

Even the more realistic goal of a gradual Europeanisation of defence spending over a period of 10-15 years would go beyond anything Europe has done in living memory. Key to their current position is the fact that the EU is not a military alliance. Defence is explicitly excluded from the single market.

The UK is not in the EU, and yet it is indispensable in the construction of any functioning European security architecture. But Europe, obdurate as ever, launched a €150bn defence fund with the participation of Japan and South Korea, and without the UK. This tells us that they are still in business-as-usual mode.

Another obstacle to military greatness is Europe’s demographics, and its lack of young people willing to join the military. There is now growing support in several EU countries to reinstitute the draft. Interestingly much of this pressure comes from politicians of the Left, who themselves avoided the draft when it was in place, and who opted for social work instead. But even if the draft were brought back, that would not suddenly present Europe with the specialist troops they need to drive battle tanks and fly F35 fighter planes.

There is a cliché about the EU that if only the crisis were big enough, Europeans might wake up and do the right thing. They had a financial crisis. They had a pandemic. They had Ukrainian crisis.

They did not wake up…

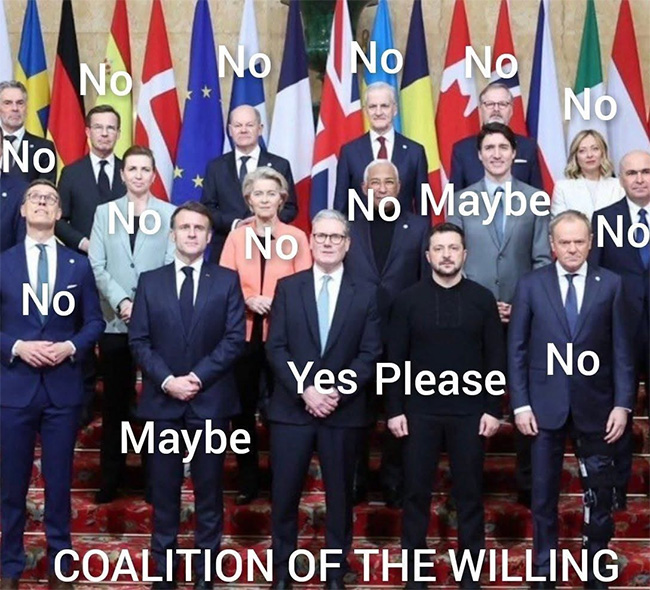

…European leaders are going to fight against Russia for Ukraine. Here is the result of their intentions:

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

10:37 01.04.2025 •

10:37 01.04.2025 •