Europeans went to the polls over four days to elect a new European Parliament. Many of those elected are critical of the European Union’s approach to the war between Ukraine and Russia, notes ‘The Courthouse News’ from California.

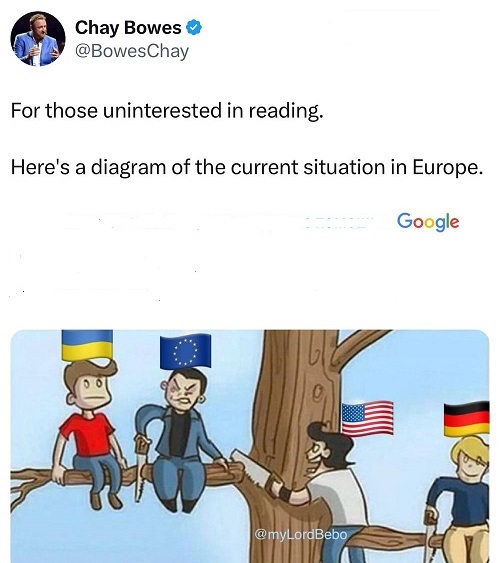

But outside the halls of power in Europe, signs of growing unease with — and even rebellion against — the EU’s unwavering support for Ukraine and determination to defeat Russia were expressed in the recent European Parliament elections as voters in Austria, Germany, France and elsewhere backed parties skeptical of hardening the conflict with Moscow.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, fresh off victorious European elections for her conservatives, announced a broadening of talks over Ukraine’s potential entry into the EU. She said Kyiv will receive 1.5 billion euros ($1.6 billion) in frozen Russian assets held in European banks to help it rebuild.

But many Europeans aren’t so sure about the high costs the EU too is paying with its determination to see Russia fail.

In Austria, the far-right Freedom Party won the most votes in the European elections on a “Stop the EU Madness” platform calling for an end to “warmongering.” With national parliamentary elections later this year, a win by the Freedom Party could see Austria join Hungary and Slovakia in calling for negotiations with Russian President Vladimir Putin to end the war.

In France, Marine Le Pen, the far-right leader with pro-Russia sympathies, trounced French President Emmanuel Macron. After the drubbing, Macron shocked Europe by announcing snap parliamentary elections, a gamble that could further strengthen Le Pen’s National Rally and erode support for Ukraine.

In Germany, those opposed to arming Ukraine — the far-right Alternative for Germany and a new radical-left party led by Sahra Wagenknecht — were the only political forces to see their ranks swell. Backing for the AfD jumped by 4.9% to climb to 15.9% and Wagenknecht’s anti-war party won 6.2% of the vote in its first elections.

“Its instant success highlights continued electoral demand for a careful course on Ukraine,” the political risk firm Teneo said in a briefing note about Wagenknecht’s success.

All of this is spooking those in Europe who see the rise of the far right as both a danger to the EU and Ukraine.

“The European Parliament elections have just demonstrated how the war — or better the perceived need to end it, accompanied by disinformation directly or indirectly sponsored by the Kremlin, affected many election campaigns and results across Europe,” said Gwendolyn Sasse, the director of the Center for East European and International Studies in Berlin.

“Wake up! After these elections, Europe is again in danger,” ran a headline in The Guardian newspaper over an opinion piece by Timothy Garton Ash, a prominent historian and commentator who is an ardent Ukraine supporter.

For some commentators, though, the election results accurately reflected worries felt by Europeans over the war’s economic consequences and the possibility of the conflict expanding.

“I think Le Pen will see a benefit in making this [election] a kind of referendum on Macron and his apparent march to war with Russia,” said Gabriel Elefteriu, an international security expert with the Council on Geostrategy think tank in London, speaking on a panel for Brussels Signal, a right-wing news outlet.

Elefteriu called the rise of a strong far right “a real political revolt in Europe and it’s here to stay.”

“The question is how will the establishment deal with this situation,” he said. “They’ve got two options: One is to try to launch some kind of war in defense of democracy and use the power of state as much as they can to try to limit the further growth of the hard right in Europe.”

Ahead of the elections, surveys showed that voters put security and soaring inflation among their top-most concerns — and both are related to the war in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Europe has watched with increasing anxiety as its sense of security has crumbled over the past 27 months of war. Now, European leaders talk with urgency about the need to prepare for armed conflict with Russia, ramp up military spending, reintroduce conscription.

France’s President Emmanuel Macron (photo), after suffering a humiliating defeat in the European Parliament elections on June 9, has dissolved the National Parliament and called for snap elections on June 30 and July 7. This step will have potentially huge implications for France’s domestic and foreign policies, particularly with respect to its support for Ukraine, writes ‘The Responsible Statecraft’.

In the European elections, 50% of the French voters participated and delivered a shocking rebuke to the establishment: 37% of the votes went to far-right populist parties, the National Rally and Reconquest, led by Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour, respectively. Another 10% landed with the far-left populist La France Insoumise.

By contrast, Macron’s centrist liberal list earned only 14.6% of the vote, less than half of the vote for the National Rally.

Modern French history provides precedents for what is known as “cohabitation” – when the president and prime minister belong to different parties. By virtue of the French constitution, the president has ample powers to sabotage the prime minister, and Macron would certainly be highly incentivized to do so should Jordan Bardella, the 28-year-old National Rally candidate, become the one.

Yet calling for elections is a huge gamble that may backfire spectacularly. The sheer scale of Le Pen party’s victory in the European elections – it won in a staggering 93% of French municipalities — places it in a strong position to win a plurality of votes in the National Assembly.

Above all else, the result shows the party’s staying power in French politics; its perennial presidential candidate, Marine Le Pen, increased her share of votes from around 34% in 2017 to 41% in 2022. If current trends are not drastically reversed, she could have a decent shot at victory in 2027.

That has major implications for France’s foreign policy, especially for Ukraine. Macron is one of Kyiv’s strongest European supporters, voicing, for example, a readiness to send Western military trainers to Ukraine and, in a dramatic policy shift, calling for permitting Ukraine to strike targets inside Russia with Western weapons.

The impending elections, whatever their outcome, won’t necessarily affect these policies because foreign policy in France is a prerogative of the president, but the sheer complexity and gravity of the war policies promoted by Macron and their implications would presumably require his full attention. Instead, Macron will likely be distracted by the elections that he has called.

In the longer term, a strong right-wing populist presence in the parliament and government may hinder plans for strengthening a common EU security and defense policy, long a major priority for Macron and for the outgoing president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, who is hoping to be reappointed to her position for a second five-year term.

As France is the EU’s main military power, Paris’ cooperation is indispensable for making the effort prosper. Doing so, however, will require not only diplomatic support, but also, crucially, financial muscle. Macron is one of the main proponents of the EU joint borrowing scheme to boost defense spending in response to the war in Ukraine. This spending by France would have to be subject to parliamentary approval.

Even if Ukraine enjoys stable support for now, how long it may endure and whether it will extend to a post-war stage remains uncertain, particularly given Le Pen’s past reluctance to back Kyiv. Moreover, given France’s status as a nuclear power and self-sufficiency in terms of its own defense, Macron’s rhetoric about the existential stakes involved in Ukraine may ring hollow to much of the French electorate, and certainly the more nationalist part of it.

It remains to be seen whether Macron’s gamble with snap elections will pay off, but it certainly risks weakening Ukraine’s cause – particularly if the populist right will manage to maintain the momentum it gained by crushing Macron’s party in last week’s European elections.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:26 17.06.2024 •

11:26 17.06.2024 •