In America's weird empire, dependents call the shots. Soon we will be suffering the consequences, writes David C. Hendrickson, a professor emeritus of political science at Colorado College and the President of the John Quincy Adams Society.

The alliance system of the United States is frequently called an empire, and for good reason. But it is a peculiar form of empire, in which the metropolitan center seems directed and ruled by the periphery. In the classic idea of empire, rule flowed from the top down. Not in this one.

This inversion is nowhere more evident than in the relationship between the United States and Israel. Biden responded to the October 7 attacks by giving Israel total support for its aim of destroying Hamas. The same pattern is apparent in policy toward Ukraine. For 18 months, the Biden administration did not dare to set limits on Ukraine’s war aims, though these anticipated, absurdly, total victory over Russia.

These certitudes, however, have begun to shake. Within the administration, there seems to have been a great awakening over the last few weeks that neither course is sustainable. The gist of recent reporting is as follows: the Ukrainians are losing the war and have to acknowledge that fact, better now than later. The Israelis are behaving barbarically and have got to be reined in, else our reputation in the world is ruined.

For 18 months, the Biden administration insisted that Ukraine’s aims were wholly its own to determine and that the United States would support them regardless. With Ukraine’s summer offensive having met with almost total failure, the administration appears to be getting cold feet. This is all very hush-hush, with “quiet” discussions reputedly going on behind the scenes. It’s probable, indeed, that Biden’s advisers are divided. Though official policy hasn’t changed a whit, the impetus to do so is clearly there.

The bind over Israel is yet more acute. According to widespread reports, Biden and his advisers believe that Israel is embarked on a mad project in Gaza. They see that the United States — having given Israel a green light, a blank check, and tons of bombs — will be held directly responsible for the awful humanitarian consequences. They don’t think Israel has defined a coherent endgame. They fear they are presiding over a moral enormity. They see a precipitous collapse in support from others.

Over the past month, Biden has warned the Israelis not to act out of anger and vengeance in retaliation for October 7, advised against a ground invasion of Gaza, and insisted that Israel seek to avoid civilian deaths as much as possible.

Last weekend, Secretary of State Antony Blinken went to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with these ideas and with a request for a “humanitarian pause.” Bibi’s response: ain’t gonna happen.

Today, 66% of Americans want a ceasefire, according to one poll, but less than five percent of the House of Representatives does, so maybe Bibi knows whereof he speaks. AIPAC is busy with attack ads against the few brave congresspeople who have criticized Israel and called for a ceasefire.

But Biden has to worry about America’s larger role in the world and is alive to the likelihood that what is coming in Gaza will wreck America’s legitimacy. Who in the non-West could ever bear again a lecture from the United States on its zealous commitment to human rights? What would this do to America’s case against Russia?

Biden’s choice is to get tough with the Israelis or to go along with what he fears is going to be a gigantic catastrophe.

Can Biden summon the will to confront Netanyahu? Will his administration force Ukraine to the bargaining table?

In our weird empire, where dependents call the shots, deeply embedded tendencies dictate a negative answer to both questions, though wise policy would dictate positive ones. Perhaps the time is ripe for a new policy in which America consults its own national interests rather than theirs, David C. Hendrickson notes.

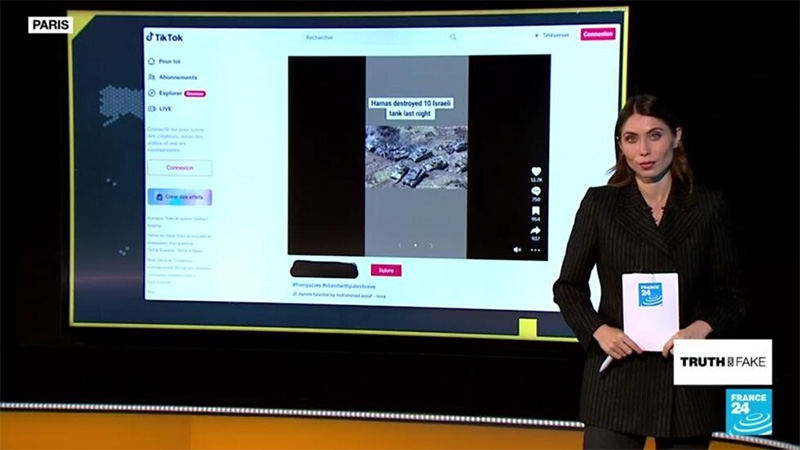

Images of war in Ukraine used to falsely illustrate Israeli ground offensive in Gaza.

Images of war in Ukraine used to falsely illustrate Israeli ground offensive in Gaza.

In fact, the war in Gaza and the war in Ukraine are not similar but quite different, both in their strategic significance and morality. Neither speaker Johnson nor GOP Ukraine war skeptics have done a good job of explaining why, but their instincts are sound, writes Scott McConnell, a founding editor of ‘The American Conservative’.

For the United States, Ukraine is almost entirely a war of choice instigated in large part by reckless American policy. The United States had no need to financially and symbolically intervene in Ukraine's domestic struggles in favor of the most anti-Russian faction, as it did under President Barack Obama during the Maidan insurrection. Russia, no longer as weak as it was in the 1990s, had begun to complain vociferously of U.S. meddling, until in 2014, it took over Crimea. As de facto military cooperation between NATO and Ukraine intensified even further under President Biden, Russia's objections become ever more shrill — only to be famously ignored.

Just for a minute imagine if an elected Mexican president was replaced in an anti-American coup supported by China, and then the new regime sought a military alliance with China. Washington would react in very much the same way Moscow did.

There are other ways we could have behaved to support Ukraine without poking the Russian bear. The United States could well have said to Ukraine, "We wish you well but you are the guarantors of your own liberty." Ukraine would have made the necessary concessions to geography, and hundreds of thousands of young men, Ukrainian and Russian, would not now be dead or maimed.

Had we done so, Russia, which has had its own bitter experiences with Islamic terrorism, would not feel credibly that the United States is committed to regime change in Moscow, and thus would not feel compelled to oppose the United States every place it can, most notably in the Middle East and Far East.

The Ukraine war is almost entirely a case of the United States — or more particularly, the narrow group of American elites which benefit from NATO expansion — going abroad looking for trouble and getting it.

But while the Ukraine war wouldn't exist without reckless American intervention, the Mideast is obviously more complicated.

It is a sense that Israel is part of whatever remains of the West's common civilization. The United States in particular but to some extent France and Germany and England, too, have been shaped by Jewish artists and intellectuals. We have Freud and his followers and Marx and his and countless brilliant Jewish novelists and Hollywood. One might roll one's eyes at the extent of this contribution, or decry some of its consequences, but it is a big part of what America is, and to deny it is to somehow deny one's own national culture.

Israel is part of the West, which is part of its difficulty in the Mideast but is also part of the reason that, when push comes to shove, most Americans will support it.

What is clear is that any country must react in an extremely forceful way to any group that wantonly murdered 1,400 of its citizens, mostly unarmed civilians. Any self-respecting country would react the same way, to the extent it had the means.

Israel is waging a just war in Gaza and an unjust war of ethnic cleansing on the West Bank. If the United States is to remain involved in the region, from which there seems no escape, it will have to begin the tedious work of supporting reasonable Israelis (and marginalizing the anti-Arab zealots) just as it needs to separate Hamas from the Palestinians who are ready to seek accommodation with Israel.

Israel and Ukraine are not part of the same struggle "against evil." Russia has reacted as any self-respecting power would to a rival seeking to build military bases on its border. Israel is reacting the way any normal country would to the brutal mass murder of its citizens. Washington policy makers should understand that, Scott McConnell stresses.

read more in our Telegram-channel https://t.me/The_International_Affairs

11:28 10.11.2023 •

11:28 10.11.2023 •